What would happen to the astronaut crews aboard NASA’s Orion deep space capsule in the event of parachute failures in the final moments before splashdown upon returning from weeks to years long forays to the Moon, Asteroids or Mars?

NASA teams are evaluating Orion’s fate under multiple scenarios in case certain of the ships various parachute systems suffer partial deployment failures after the blistering high speed reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere.

Orion is nominally outfitted with multiple different parachute systems including two drogue chutes and three main chutes that are essential for stabilizing and slowing the crewed spacecraft for safely landing in the Pacific Ocean upon concluding a NASA ‘Journey to Mars’ mission.”

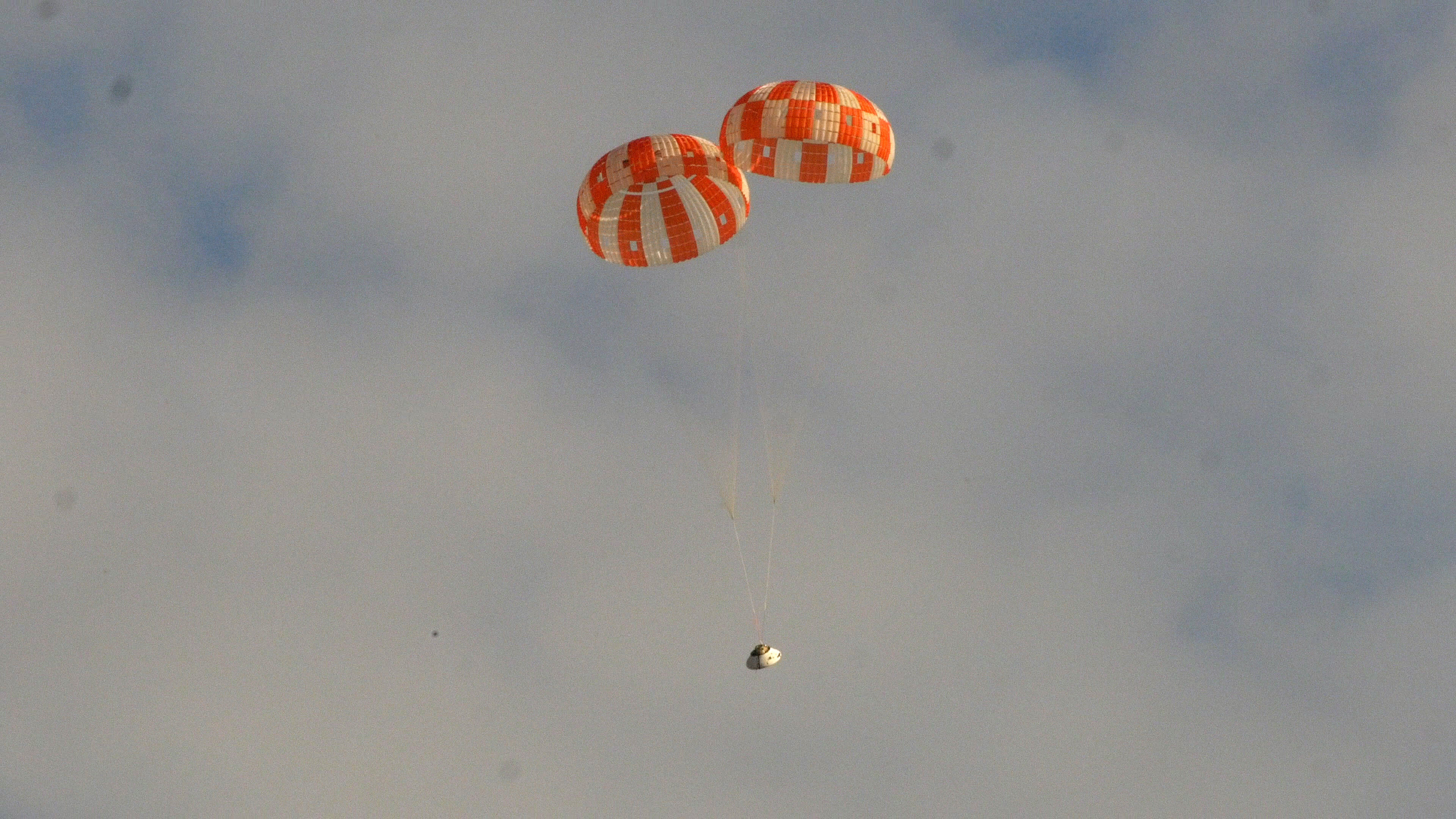

This week engineers from NASA and prime contractor Lockheed Martin ran a dramatic and successful six mile high altitude drop test in the skies over the Arizona desert, in the instance where one of the parachutes in each of Orion’s drogue and main systems was intentionally set to fail.

“We test Orion’s parachutes to the extremes to ensure we have a safe system for bringing crews back to Earth on future flights, even if something goes wrong,” says CJ Johnson, project manager for Orion’s parachute system, in a statement.

“Orion’s parachute performance is difficult to model with computers, so putting them to the test in the air helps us better evaluate and predict how the system works.”

Although Orion hits the atmosphere at over 24,000 mph after returning from deep space, it slows significantly after atmospheric reentry.

By the time the first parachutes normally deploy, the crew module has decelerated to some 300 mph. Their job is to slow the craft down to about 20 mph by the time of ocean splashdown mere minutes later.

On Aug. 26, NASA conducted a 35,000 foot high drop test out of the cargo bay of a C-17 aircraft using an engineering test version of the Orion capsule over the U.S. Army Yuma Proving Ground in Yuma, Arizona.

“The engineering model has a mass similar to that of the Orion capsule being developed for deep space missions, and similar interfaces with its parachute system,” say officials.

“Engineers purposefully simulated a failure scenario in which one of the two drogue parachutes, used to slow and stabilize Orion at high altitude, and one of its three main parachutes, used to slow the crew module to landing speed, did not deploy.”

Here’s a video detailing the entire drop test sequence of events from preflight preparations to the parachute landing.

The high-risk Aug. 26 experiment was NASA’s penultimate drop test in this engineering evaluations series. A new series of tests in 2016 will serve to qualify the parachute system for crewed flights.

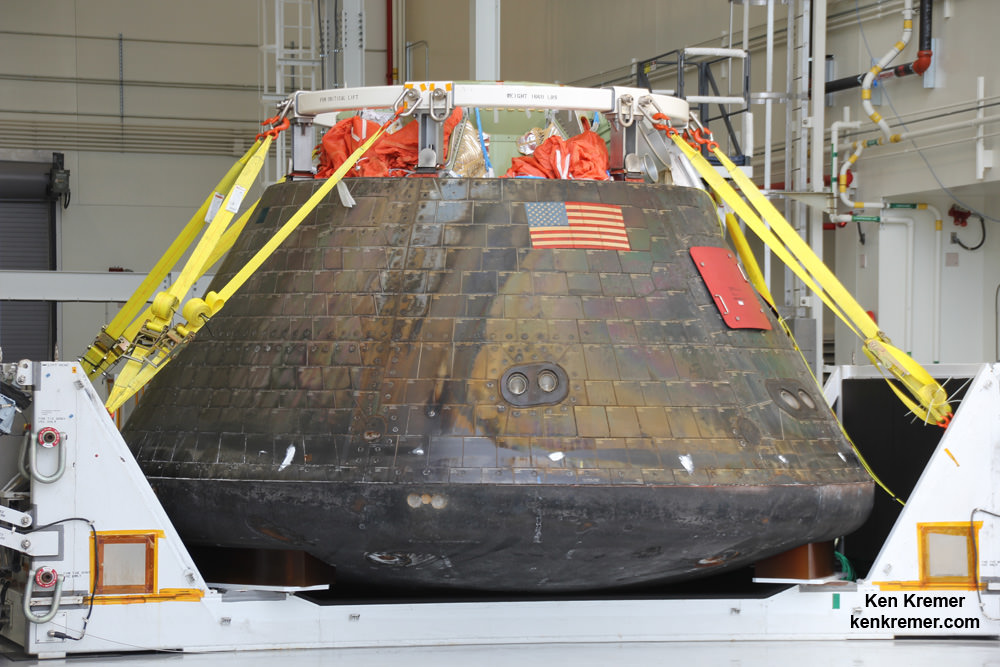

Orion’s inaugural mission dubbed Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT) was successfully launched on a flawless flight on Dec. 5, 2014 atop a United Launch Alliance Delta IV Heavy rocket Space Launch Complex 37 (SLC-37) at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

The parachutes operated flawlessly during the Orion EFT-1 mission.

Orion’s next launch is set for the uncrewed test flight called Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1). It will blast off on the inaugural flight of NASA’s SLS heavy lift monster rocket concurrently under development – from Launch Complex 39-B at the Kennedy Space Center.

The maiden SLS test flight is targeted for no later than November 2018 and will be configured in its initial 70-metric-ton (77-ton) version with a liftoff thrust of 8.4 million pounds. It will boost an unmanned Orion on an approximately three week long test flight beyond the Moon and back.

Toward that goal, NASA is also currently testing the RS-25 first stage engines that will power SLS – as outlined in my recent story here.

NASA plans to gradually upgrade the SLS to achieve an unprecedented lift capability of 130 metric tons (143 tons), enabling the more distant missions even farther into our solar system.

Homecoming view of NASA’s first Orion spacecraft after returning to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Dec. 19, 2014 after successful blastoff on Dec. 5, 2014. Credit: Ken Kremer – kenkremer.com

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.

………….

Learn more about MUOS-4 USAF launch, Orion, SLS, SpaceX, Boeing, ULA, Space Taxis, Mars rovers, Orbital ATK, Antares, NASA missions and more at Ken’s upcoming outreach events:

Aug 31- Sep 2: “MUOS-4 launch, Orion, Commercial crew, Curiosity explores Mars, Antares and more,” Kennedy Space Center Quality Inn, Titusville, FL, evenings

My only question is if there is an emergency over-ride to deploy the various chutes if the automated deployment fails. I don’t know enough of the project to know this part.

Because it is stable in a near-inverted position (it won’t right itself) Orion has flotation ‘balloons’ near the top that will push it up enough to take itself to an upright position.

Apollo carried similar hardware for exactly the same reasons, and sometimes did end up in the ‘Stable-2’ position. Those bags inflated unconditionally on splashdown, even if the capsule stayed in the upright ‘Stable-1’ position. I must assume Orion will follow that model.

I noticed that with only 2 chutes deployed, the capsule did not always present the ‘heat shield’ side downward. Is there an inflatable ring? How does hitting the water edge first effect the capsule traveling as it were 30% faster? Would the capsule slip more easily beneath the waves, then bob back up? Not a big deal if the swell and winds cooperate?

I noticed that too. The article says the main chutes slow the capsule from 300 mph to 20 mph for landing. At 300 mph, the heat shields have already done their job. So agreed, it’s a question of how the splashdown will be affected. Too bad the video didn’t show that.

I guess the three chutes support in a triangular configuration and that’s why when one is missing the capsule is not level? I wonder if they could add some backup cables to support each corner of the triangle from the other two sides in case of a failure of one, to keep the capsule level.

good q’s – will chk

Couldn’t they just add a reserve parachute, it can’t weigh that much? Cheaper than going through this test of a failure. I can imagine many fail tests for them to perform. It’s getting creepy how the SLS+Orion project must redesign and test everything and anything. It seems as if they are doing it just for fun and money, not with any serious intention to actually move anything to anyplace.

“Couldn’t they just add a reserve parachute, it can’t weigh that much? Cheaper than going through this test of a failure”

Think of it as being similar to determining the actual ‘engine out’ capability of an aircraft. Having one of three fail is designed to be tolerable, even though not optimal. But you can’t be sure if it’s as tolerable as you intended, until you try it.

And yes, that additional reserve chute mass (including the likely additional structural mass) does matter. Besides, a reserve parachute might find itself getting snarled in whatever happened to the failed main chute…or worse, interfering with a good chute. Deployment is simpler, when you can get them all out there at once.

I still think it is a not helpful-for-space-travel jobs program to test out a failed parachute landing. Given this they could try out anything for ever and never launch anyone. I begin to think that this is the actual plan. To just suck up money without achieving anything.

On the other hand, it could be considered irresponsible to *not* test a failure mode of this sort.

And an easily tested one, at that. This doesn’t require a rocket launch, it’s pushed out of a common military cargo plane that’s already designed for parachute drop of heavy equipment.

Surely you accept testing a normal parachute deployment? It takes no more effort to do the same with one less parachute.

I wish I knew more after reading this article and watching the video than I did before. Like Aqua4U, I noticed the edge-on orientation of the capsule, and I have to wonder if it is problematic. Also, I wonder what the velocity of the capsule was while it was descending with only two chutes, and what that velocity would mean to a crew.

The capsule was fitted out with a myriad of sensors to measure all these factors – not sure how much of the collected data will be made public once it’s been sifted through though.