Okay, so this article is Colonizing the Outer Solar System, and is actually part 2 of our team up with Fraser Cain of Universe Today, who looked at colonizing the inner solar system. You might want jump over there now and watch that part first, if you are coming in from having seen part 1, welcome, it is great having you here.

Without further ado let us get started. There is no official demarcation between the inner and outer solar system but for today we will be beginning the outer solar system at the Asteroid Belt.

The Asteroid Belt is always of interest to us for colonization. We have talked about mining them before if you want the details on that but for today I’ll just remind everyone that there are very rich in metals, including precious metals like gold and platinum, and that provides all the motivation we need to colonize them. We have a lot of places to cover so we won’t repeat the details on that today.

You cannot terraform asteroids the way you could Venus or Mars so that you could walk around on them like Earth, but in every respect they have a lot going for them as a candidate. They’ve got plenty for rock and metal for construction, they have lots of the basic organic elements, and they even have some water. They also get a decent amount of sunlight, less than Mars let alone Earth, but still enough for use as a power source and to grow plants.

But they don’t have much gravity, which – pardon the pun – has its ups and downs. There just isn’t much mass in the Belt. The entire thing has only a small fraction of the mass of our moon, and over half of that is in the four biggest asteroids, essentially dwarf planets in their own right. The remainder is scattered over millions of asteroids. Even the biggest, Ceres, is only about 1% of 1% of Earth’s mass, has a surface gravity of 3% Earth-normal, and an escape velocity low enough most model rockets could get into orbit. And again, it is the biggest, most you could get away from by jumping hard and if you dropped an object on one it might take a few minutes to land.

You can still terraform one though, by definition too. The gentleman who coined the term, science fiction author Jack Williamson, who also coined the term genetic engineering, used it for a smaller asteroid just a few kilometers across, so any definition of terraforming has to include tiny asteroids too.

Of course in that story it’s like a small planet because they had artificial gravity, we don’t, if we want to fake gravity without having mass we need to spin stuff around. So if we want to terraform an asteroid we need to hollow it out and fill it with air and spin it around.

Of course you do not actually hollow out the asteroid and spin it, asteroids are loose balls of gravel and most would fly apart given any noticeable spin. Instead you would hollow it out and set a cylinder spinning inside it. Sort of like how a good thermos has an outside container and inside one with a layer of vacuum in between, we would spin the inner cylinder.

You wouldn’t have to work hard to hollow out an asteroid either, most aren’t big enough to have sufficient gravity and pressure to crush an empty beer can even at their center. So you can pull matter out from them very easily and shore up the sides with very thin metal walls or even ice. Or just have your cylinder set inside a second non-spinning outer skin or superstructure, like your washer or dryer.

You can then conduct your mining from the inside, shielded from space. You could ever pressurize that hollowed out area if your spinning living area was inside its own superstructure. No gravity, but warmth and air, and you could get away with just a little spin without tearing it apart, maybe enough for plants to grow to normally.

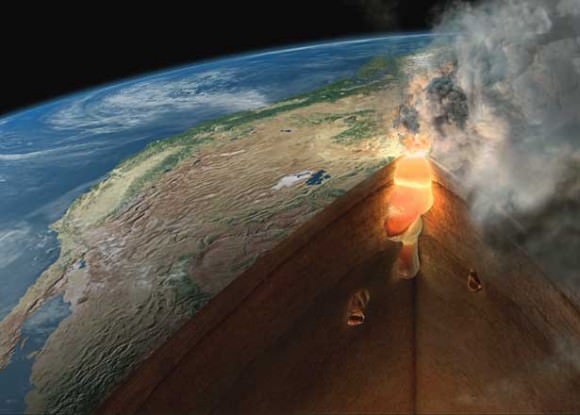

It should be noted that you can potentially colonize even the gas giants themselves, even though our focus today is mostly on their moons. That requires a lot more effort and technology then the sorts of colonies we are discussing today, Fraser and I decided to keep things near-future and fairly low tech, though he actually did an article on colonizing Jupiter itself last year that was my main source material back before got to talking and decided to do a video together.

Hydrogen is plentiful on Jupiter itself and floating refineries or ships that fly down to scoop it up might be quite useful, but again today we are more interested in its moons. The biggest problem with colonizing the moons of Jupiter is all the radiation the planet gives off.

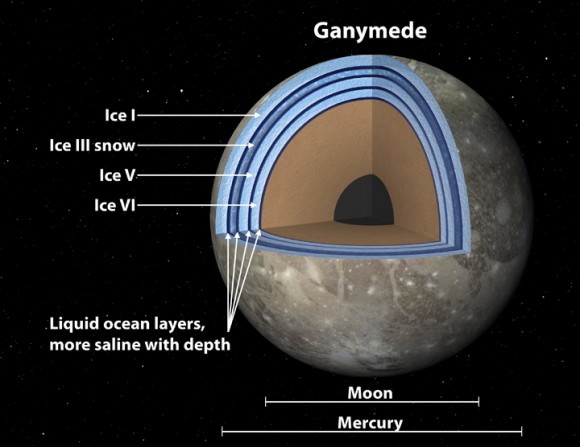

Europa is best known as a place where the surface is covered with ice but beneath it is thought to be a vast subsurface ocean. It is the sixth largest moon coming right behind our own at number five and is one of the original four moons Galileo discovered back in 1610, almost two centuries before we even discovered Uranus, so it has always been a source of interest. However as we have discovered more planets and moons we have come to believe quite a few of them might also have subsurface oceans too.

Now what is neat about them is that water, liquid water, always leaves the door open to the possibility of life already existing there. We still know so little about how life originally evolved and what conditions permit that to occur that we cannot rule out places like Europa already having their own plants and animals swimming around under that ice.

They probably do not and obviously we wouldn’t want to colonize them, beyond research bases, if they did, but if they do not they become excellent places to colonize. You could have submarine cities in such places floating around in the sea or those buried in the surface ice layer, well shielded from radiation and debris. The water also geysers up to the surface in some places so you can start off near those, you don’t have to drill down through kilometers of ice on day one.

Water, and hydrogen, are also quite uncommon in the inner solar system so having access to a place like Europa where the escape velocity is only about a fifth of our own is quite handy for export. Now as we move on to talk about moons a lot it is important to note that when I say something has a fifth of the escape velocity of Earth that doesn’t mean it is fives time easier to get off of. Energy rises with the square of velocity so if you need to go five times faster you need to spend 5-squared or 25 times more energy, and even more if that place has tons of air creating friction and drag, atmospheres are hard to claw your way up through though they make landing easier too. But even ignoring air friction you can move 25 liters of water off of Europa for every liter you could export from Earth and even it is a very high in gravity compared to most moons and comets. Plus we probably don’t want to export lots of water, or anything else, off of Earth anyway.

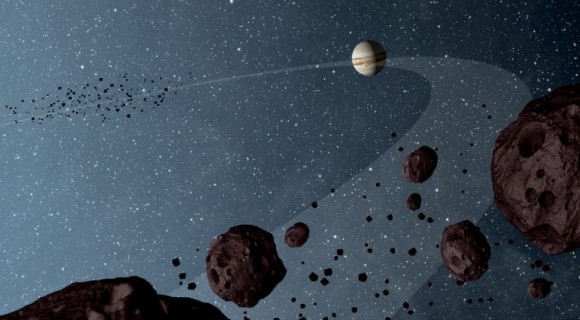

We should start by noting two things. First, the Asteroid Belt is not the only place you find asteroids, Jupiter’s Trojan Asteroids are nearly as numerous, and every planet, including Earth, has an equivalent to Jupiter’s Trojan Asteroids at its own Lagrange Points with the Sun. Though just as Jupiter dwarfs all the other planets so to does its collection of Lagrangian objects. They can quite big too, the largest 624 Hektor, is 400 km across, and has a size and shape similar to Pennsylvania.

And as these asteroids are at stable Lagrange Points, they orbit with Jupiter but always ahead and behind it, making transit to and from Jupiter much easier and making good waypoints.

Before we go out any further in the solar system we should probably address how you get the energy to stay alive. Mars is already quite cold compared to Earth, and the Asteroids and Jupiter even more so, but with thick insulation and some mirrors to bounce light in you can do fairly decently. Indeed, sunlight out by Jupiter is already down to just 4% of what Earth gets, meaning at Jovian distances it is about 50 W/m²

That might not sound like much but it is actually almost a third of what average illumination is on Earth, when you factor in atmospheric reflection, cloudy days, nighttime, and higher, colder latitudes. It is also a good deal brighter than the inside of most well-lit buildings, and is enough for decently robust photosynthesis to grow food. Especially with supplemental light from mirrors or LED growth lamps.

But once you get out to Saturn and further that becomes increasingly impractical and a serious issue, because while food growth does not show up on your electric bill it is what we use virtually all our energy for. Closer in to the sun we can use solar panels for power and we do not need any power to grow food. As we get further out we cannot use solar and we need to heat or cold habitats and supply lighting for food, so we need a lot more power even as our main source dries up.

So what are our options? Well the first is simple, build bigger mirrors. A mirror can be quite large and paper thin after all. Alternatively we can build those mirrors far away, closer to the sun, and and either focus them on the place we want illuminated or send an energy beam, microwaves perhaps or lasers, out to the destination to supply energy.

We also have the option of using fission, if we can find enough Uranium or Thorium. There is not a lot of either in the solar system, in the area of about one part per billion, but that does amount to hundreds of trillions of tons, and it should only take a few thousand tons a year to supply Earth’s entire electric grid. So we would be looking at millions of years worth of energy supply.

Of course fusion is even better, particularly since hydrogen becomes much more abundant as you get further from the Sun. We do not have fusion yet, but it is a technology we can plan around probably having inside our lifetimes, and while uranium and thorium might be counted in parts per billion, hydrogen is more plentiful than every other element combines, especially once you get far from the Sun and Inner Solar System.

So it is much better power source, an effectively unlimited one except on time scales of billions and trillion of years. Still, if we do not have it, we still have other options. Bigger mirrors, beaming energy outwards from closer to the Sun, and classic fission of Uranium and Thorium. Access to fusion is not absolutely necessary but if you have it you can unlock the outer solar system because you have your energy supply, a cheap and abundant fuel supply, and much faster and cheaper spaceships.

Of course hydrogen, plain old vanilla hydrogen with one proton, like the sun uses for fusion, is harder to fuse than deuterium and may be a lot longer developing, we also have fusion using Helium-3 which has some advantages over hydrogen, so that is worth keeping in mind as well as we proceed outward.

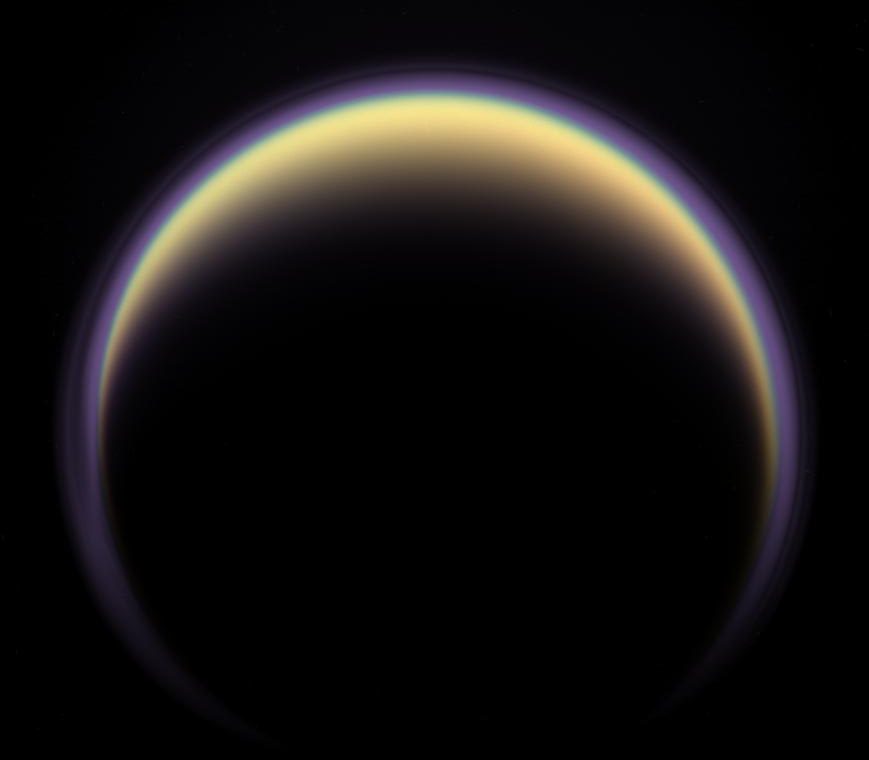

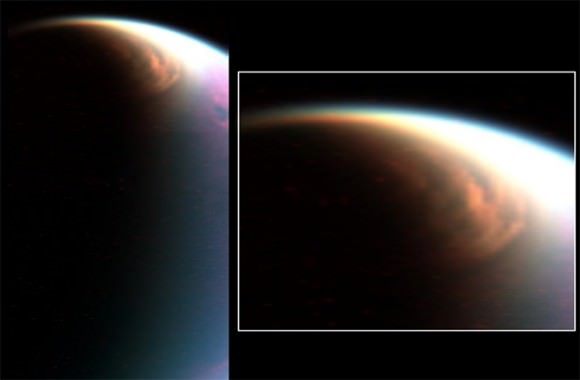

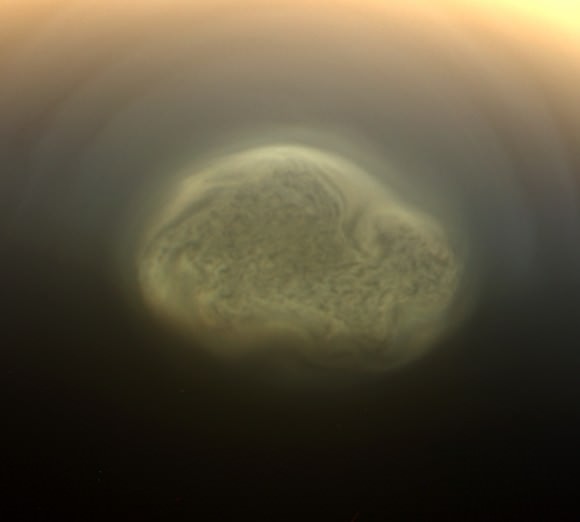

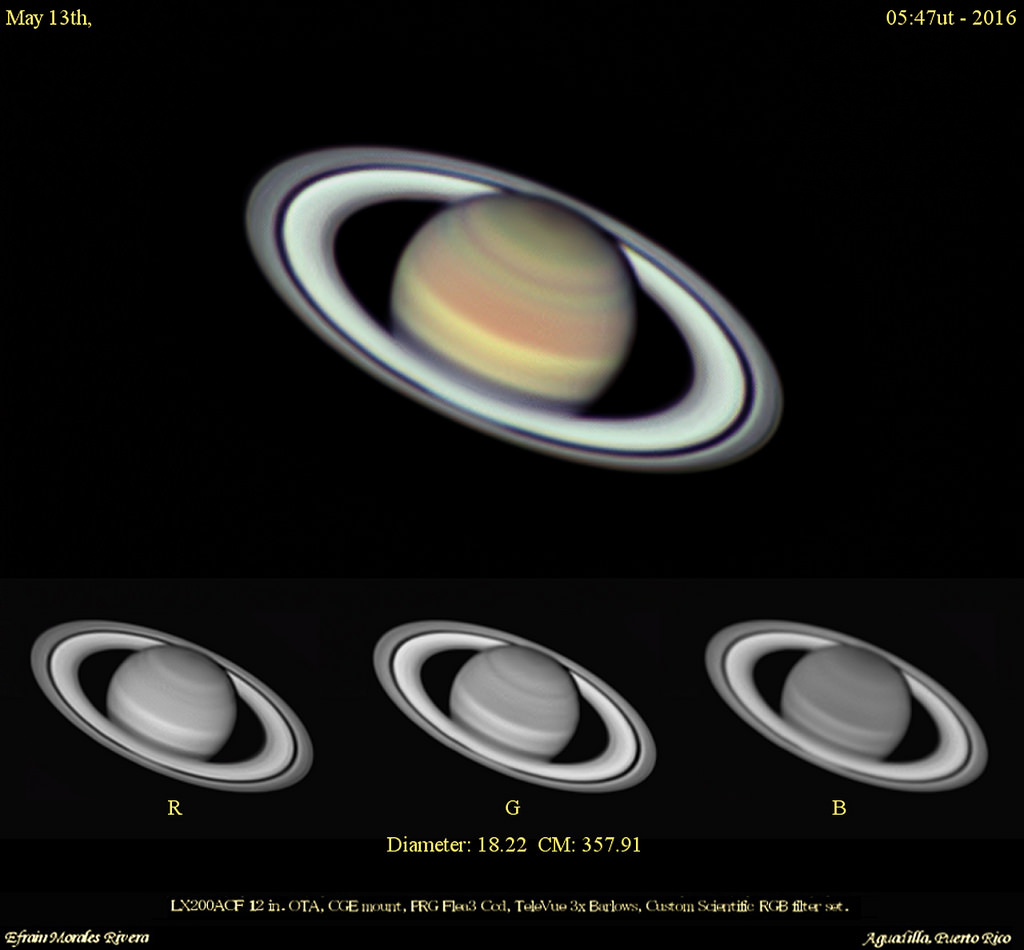

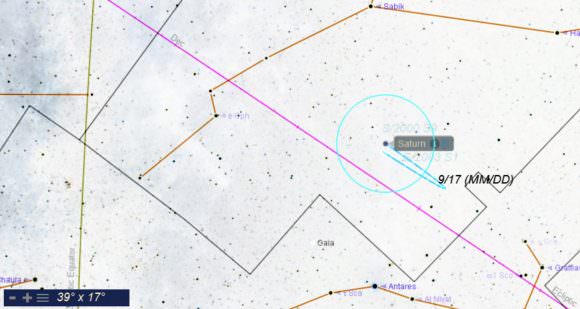

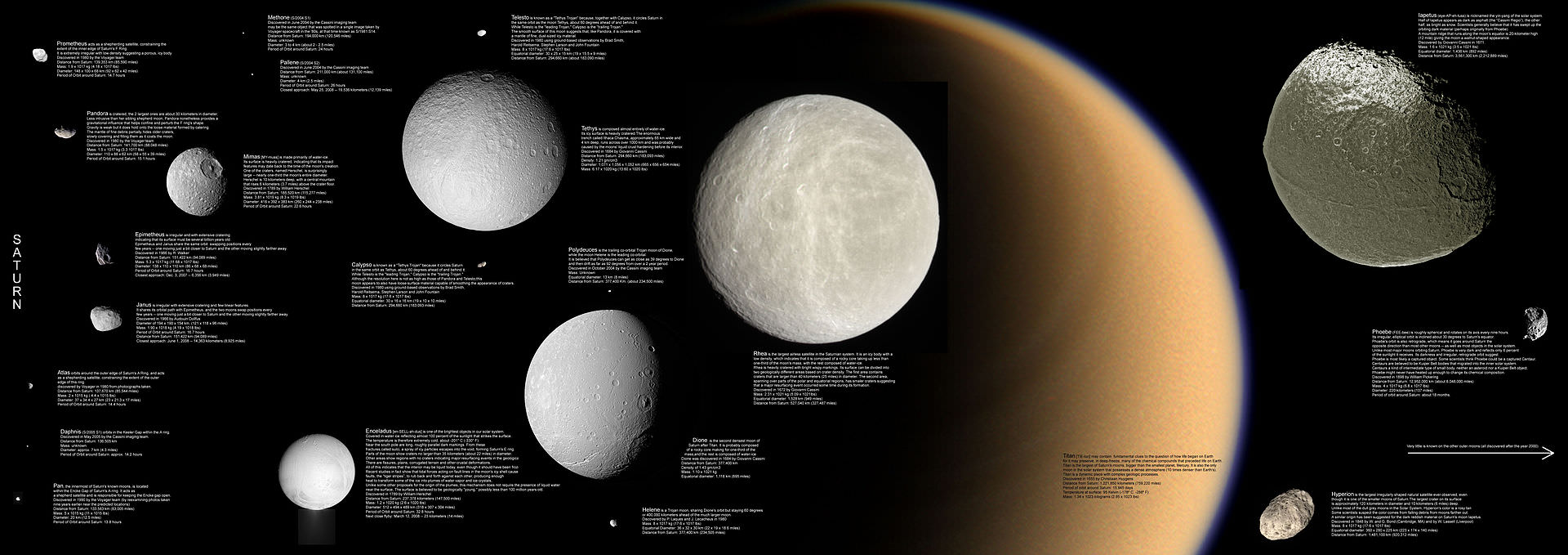

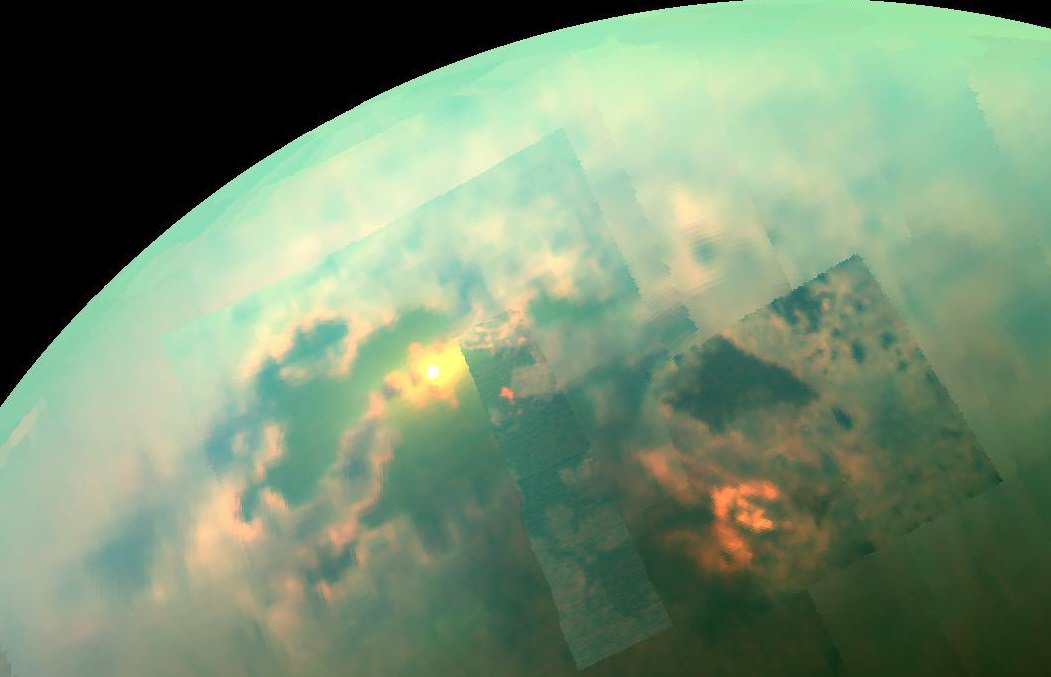

Okay, let’s move on to Saturn, and again our focus is on its moons more than the planet itself. The biggest of those an the most interesting for colonization is Titan.

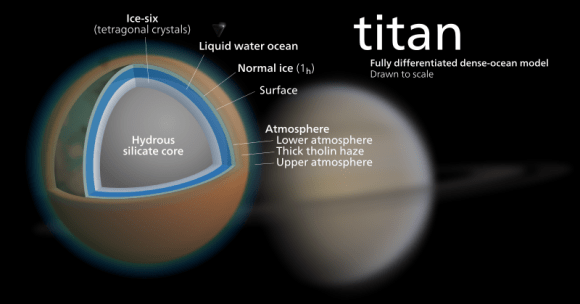

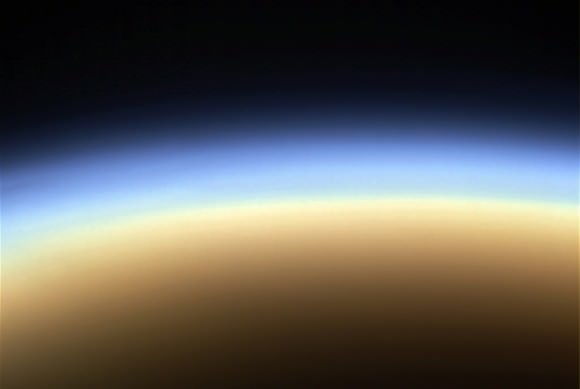

Titan is aptly named, this titanic moon contains more mass than than all of Saturn’s sixty or so other moons and by an entire order of magnitude at that. It is massive enough to hold an atmosphere, and one where the surface pressure is 45% higher than here on Earth. Even though Titan is much smaller than Earth, its atmosphere is about 20% more massive than our own. It’s almost all nitrogen too, even more than our own atmosphere, so while you would need a breather mask to supply oxygen and it is also super-cold, so you’d need a thick insulated suit, it doesn’t have to be a pressure suit like it would on Mars or almost anyplace else.

There’s no oxygen in the atmosphere, what little isn’t nitrogen is mostly methane and hydrogen, but there is plenty of oxygen in the ice on Titan which is quite abundant. So it has everything we need for life except energy and gravity. At 14% of earth normal it is probably too low for people to comfortably and safely adapt to, but we’ve already discussed ways of dealing with that. It is low enough that you could probably flap your arms and fly, if you had wing attached.

It needs some source of energy though, and we discussed that. Obviously if you’ve got fusion you have all the hydrogen you need, but Titan is one of those places we would probably want to colonize early on if we could, it is something you need a lot of to terraform other places, and is also rich in a lot of the others things we want. So we often think of it as a low-tech colony since it is one we would want early on.

In an scenario like that it is very easy to imagine a lot of local transit between Titan and its smaller neighboring moons, which are more rocky and might be easier to dig fissile materials like Uranium and Thorium out of. You might have a dozen or so small outposts on neighboring moons mining fissile materials and other metals and a big central hub on Titan they delivered that too which also exported Nitrogen to other colonies in the solar system.

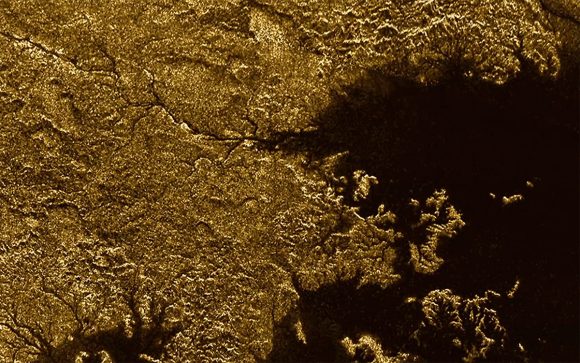

Moving back and forth between moons is pretty easy, especially since things landing on Titan can aerobrake quite easily, whereas Titan itself has a pretty strong gravity well and thick atmosphere to climb out of but is a good candidate for a space elevator, since it requires nothing more sophisticated than a Lunar Elevator on our own moon and has an abundant supply of the materials needed to make Zylon for instance, a material strong enough to make an elevator there and which we can mass manufacture right now.

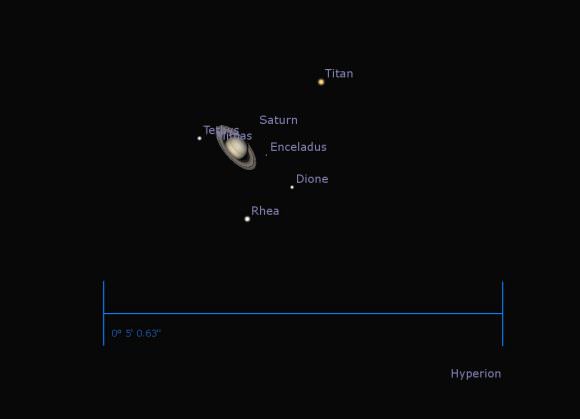

Titan might be the largest and most useful of Saturn’s moons, but again it isn’t the only one and not all of the other are just rocks for mining. At last count it has over sixty and many of them quite large. One of those, Enceladus, Saturn’s sixth largest moon, is a lot like Jupiter’s Moon Europa, in that we believe it has a large and thick subsurface ocean. So just like Europa it is an interesting candidate for Colonization. So Titan might be the hub for Saturn but it wouldn’t be the only significant place to colonize.

While Saturn is best known for its amazing rings, they tend to be overlooked in colonization. Now those rings are almost all ice and in total mass about a quarter as much as Enceladus, which again is Saturn’s Sixth largest moon, which is itself not even a thousandth of the Mass of Titan.

In spite of that the rings are not a bad place to set up shop. Being mostly water, they are abundant in hydrogen for fusion fuel and have little mass individually makes them as easy to approach or leave as an asteroid. Just big icebergs in space really, and there are many moonlets in the rings that can be as large as half a kilometer across. So you can burrow down inside one for protection from radiation and impacts and possibly mine smaller ones for their ice to be brought to places where water is not abundant.

In total those rings, which are all frozen water, only mass about 2% of Earth’s oceans, and about as much as the entire Antarctic sheet. So it is a lot of fresh water that is very easy to access and move elsewhere, and ice mines in the rings of Saturn might be quite useful and make good homes. Living inside an iceball might not sound appealing but it is better than it sounds like and we will discuss that more when we reach the Kupier Belt.

But first we still have two more planets to look at, Uranus and Neptune.

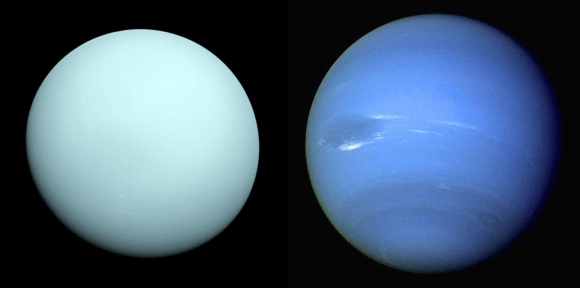

Uranus, and Neptune, are sometimes known as Ice Giants instead of Gas Giants because it has a lot more water. It also has more ammonia and methane and all three get called ices in this context because they make up most of the solid matter when you get this far out in the solar system.

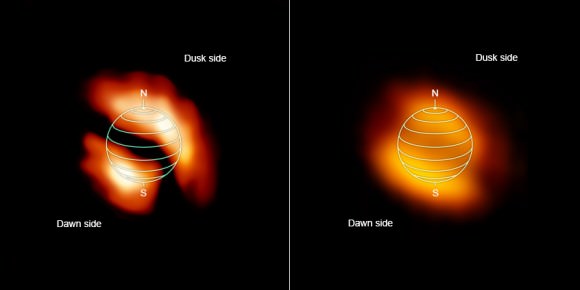

While Jupiter is over a thousand times the mass of Earth, Uranus weighs in at about 15 times the Earth and has only about double the escape velocity of Earth itself, the least of any of the gas giants, and it’s strange rotation, and its strange tilt contributes to it having much less wind than other giants. Additionally the gravity is just a little less than Earth’s in the atmosphere so we have the option for floating habitats again, though it would be a lot more like a submarine than a hot air balloon.

Like Venus, Uranus has very long days, at least in terms of places receiving continual sunlight, the poles get 42 years of perpetual sunlight then 42 of darkness. Sunlight being a relative term, the light is quite minimal especially inside the atmosphere. The low wind in many places makes it a good spot for gas extraction, such as Helium-3, and it’s a good planet to try to scoop gas from or even have permanent installations.

Now Uranus has a large collection of moons as well, useful and colonizable like the other moons we have looked at, but otherwise unremarkable beyond being named for characters from Shakespeare, rather than the more common mythological names. None have atmospheres though there is a possibility Oberon or Titania might have subsurface oceans.

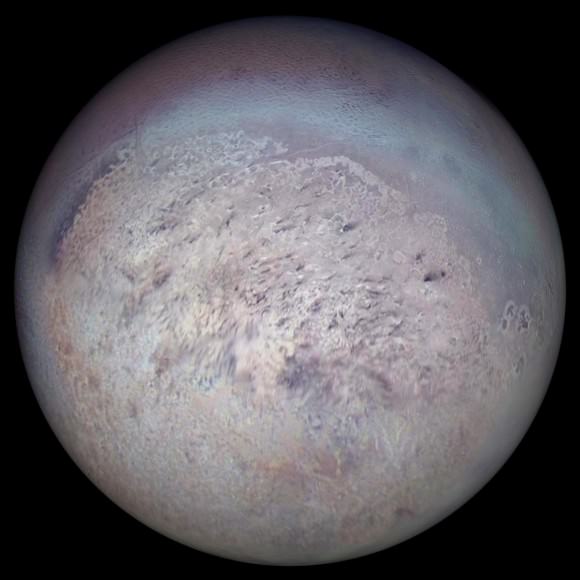

Neptune makes for a brief entry, it is very similar to Uranus except it has the characteristically high winds of gas giants that Uranus’s skewed poles mitigate, meaning it has no advantages over Uranus and the disadvantages of high wind speeds everywhere and being even further from the Sun. It too has moons and one of them, Triton, is thought to have subsurface oceans as well. Triton also presumably has a good amount of nitrogen inside it since it often erupts geysers of nitrogen from its surface.

Triton is one of the largest moons in the solar system, coming in seventh just after our Moon, number 5, and Europa at number 6. Meaning that were it not a moon it would probably qualify as a Dwarf Planet and it is often thought Pluto might be an escaped moon Neptune. So Triton might be one that didn’t escape, or didn’t avoid getting captured. In fact there are an awful lot of bodies in this general size range and composition wandering about in the outer regions of our solar system as we get out into the Kuiper Belt.

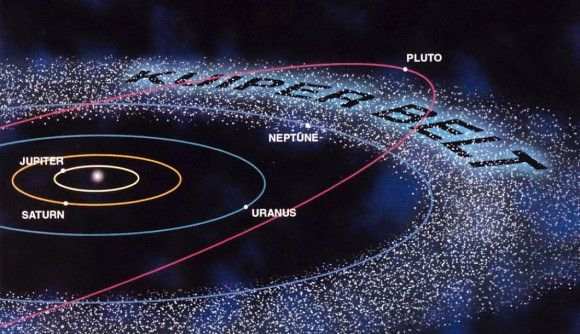

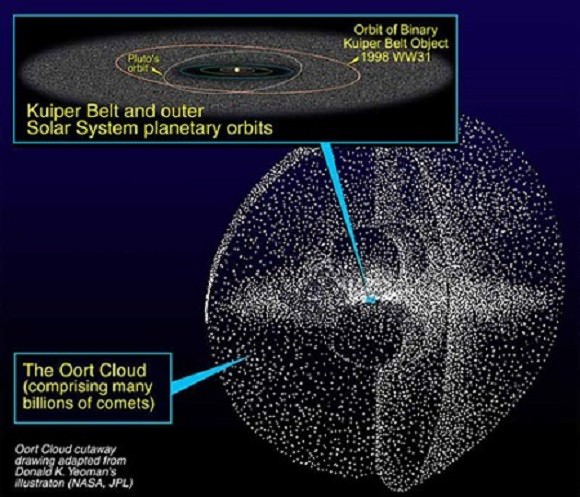

The Kuiper Belt is one of those things that has a claim on the somewhat arbitrary and hazy boundary marking the edge of the Solar System. It extends from out past Neptune to beyond Pluto and contains a good deal more mass than the asteroid Belt. It is where a lot of our comets come from and while there is plenty of rocks out there they tend to be covered in ice. In other words it is like our asteroid belt only there’s more of it and the one thing the belt is not very abundant in, water and hydrogen in general, is quite abundant out there. So if you have a power source life fusion they can be easily terraformed and are just as attractive as a source of minerals as the various asteroids and moons closer in.

We mentioned the idea of living inside hollowed out asteroids earlier and you can use the same trick for comets. Indeed you could shape them to be much bigger if you like, since they would be hollow and ice isn’t hard to move and shape especially in zero gravity. Same trick as before, you place a spinning cylinder inside it. Not all the objects entirely ice and indeed your average comet is more a frozen ball of mud then ice with rocky cores. We think a lot of near Earth Asteroids are just leftover comets. So they are probably pretty good homes if you have fusion, lots of fuel and raw materials for both life and construction.

This is probably your cheapest interstellar spacecraft too, in terms of effort anyway. People often talk about re-directing comets to Mars to bring it air and water, but you can just as easily re-direct it out of the solar system entirely. Comets tend to have highly eccentric orbits, so if you capture one when it is near the Sun you can accelerate it then, actually benefiting from the Oberth Effect, and drive it out of the solar system into deep space. If you have a fusion power source to live inside one then you also have an interstellar spaceship drive, so you just carve yourself a small colony inside the comet and head out into deep space.

You’ve got supplies that will last you many centuries at least, even if it were home to tens of thousand of people, and while we think of smaller asteroids and comets as tiny, that’s just in comparison to planets. These things tend to be the size of mountain so there is plenty of living space and a kilometer of dirty ice between you and space makes a great shield against even the kinds of radiation and collisions you can experience at relativistic speeds.

Now the Oort Cloud is much like the Kupier Belt but begins even further out and extends out probably an entire light year or more. We don’t have a firm idea of its exact dimensions or mass, but the current notion is that it has at least several Earth’s worth of mass, mostly in various icy bodies. These will be quite numerous, estimates usually assumes at least trillion icy bodies a kilometer across or bigger, and even more smaller ones. However the volume of space is so large that those kilometer wide bodies might each be a around a billion kilometers distant from neighbors, or about a light hour. So it is spread out quite thinly, and even the inner edge is about 10 light days away.

That means that from a practical standpoint there is no source of power out there, the sun is simply too diffuse for even massive collections of mirrors and solar panels to be of use. It also means light-speed messages home or to neighbors are quite delayed. So in terms of communication it is a lot more like pre-modern times in sparsely settled lands where talking with your nearest neighbors might require an hour long walk over to their farm, and any news from the big cities might take months to percolate out to you.

There’s probably uranium and thorium out there to be found, maybe a decent amount of it, so fission as a power source is not ruled out. If you have fusion instead though each of these kilometer wide icy bodies is like a giant tank of gasoline, and as with the Kupier Belt, ice makes a nice shield against impacts and radiation.

And while there might be trillions of kilometer wide chunks of ice out there, and many more smaller bodies, you would have quite a few larger ones too. There are almost certainly tons of planets in the Pluto size-range out these, and maybe even larger ones. Even after the Oort cloud you would still have a lot of these deep space rogue planets which could bridge the gap to another solar system’s Oort Cloud. So if you have fusion you have no shortage of energy, and could colonize trillions of these bodies. There probably is a decent amount of rock and metal out there too, but that could be your major import/export option shipping home ice and shipping out metals.

That’s the edge of the Solar System so that’s the end of this article. If you haven’t already read the other half, colonizing the inner Solar System, head on over now.

![The northern polar area of Titan and Vid Flumina drainage basin. (left) On top of the image, the Ligeia Mare; in the lower right the North Kraken Mare; the two seas are connected each other by a labyrinth of channels. On the left, near the North pole, the Punga Mare. Red arrows indicate the position of the two flumina significant for this work. At the end of its mission (15 September 2017) the Cassini RADAR in its imaging mode (SAR+ HiSAR) will have covered a total area of 67% of the surface of Titan [Hayes, 2016]. Map credits: R. L. Kirk. (right) Highlighted in yellow are the half-power altimetric footprints within the Vid Flumina drainage basin and the Xanthus Flumen course for which specular reflections occurred. At 1400?km of spacecraft altitude, the Cassini antenna 0.35° central beam produces footprints of about 8.5?km in diameter (diameter of yellow circles). Credit: NASA/JPL](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/grl54735-fig-0001-580x282.png)