[/caption]

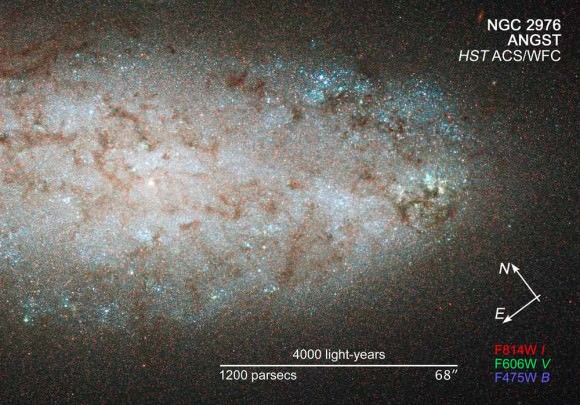

Most galaxies are throughout the universe are happenin’ places, with all sorts of raucous star formation going on. But for a nearby, small spiral galaxy, the star-making party is almost over. In this latest Hubble release, astronomers were surprised to find that star-formation activities in the outer regions of NGC 2976 are fizzling out, and any celebrating is confined to a few die-hard partygoers huddled in the galaxy’s inner region.

The reason? Well, the star birth began when another party-crashing galaxy interacted with NGC 2976. But that happened long ago, and now star formation in the galaxy is fizzling out in the outer parts as some of the gas was stripped away and the rest collapsed toward the center. With no gas left to fuel the party, more and more regions of the galaxy are going to sleep.

“Astronomers thought that grazing encounters between galaxies can cause the funneling of gas into a galaxy’s core, but these Hubble observations provide the clearest view of this phenomenon,” explains astronomer Benjamin Williams of the University of Washington in Seattle, who directed the Hubble study, which is part of the ACS Nearby Galaxy Survey Treasury (ANGST) program. “We are catching this galaxy at a very interesting time. Another 500 million years and the party will be over.”

NGC 2976 does not look like a typical spiral galaxy. It has a star-forming disk, but no obvious spiral pattern. Its gas is centrally concentrated, but it does not have a central bulge of stars. The galaxy resides on the fringe of the M81 group of galaxies, located about 12 million light-years away in the constellation Ursa Major.

“The galaxy looks weird because an interaction with the M81 group about a billion years ago stripped some gas from the outer parts of the galaxy, forcing the rest of the gas to rush toward the galaxy’s center, where it is has little organized spiral structure,” Williams says.

The galaxy’s relatively close distance to Earth allowed Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) to resolve hundreds of thousands of individual stars. What look like grains of sand in the image are actually individual stars. Studying the individual stars allowed astronomers to determine their color and brightness, which provided information about when they formed.

The image was taken over a period in late 2006 and early 2007.

“This type of observation is unique to Hubble,” Williams says. “If we had not been able to pick out individual stars, we would have known that the galaxy is weird, but we would not have dug up evidence for a significant gas rearrangement in the galaxy, which caused the stellar birth zone to shrink toward the galaxy’s center.”

Simulations predict that the same “gas-funneling” mechanism may trigger starbursts in the central regions of other dwarf galaxies that interact with larger neighbors. The trick to studying the effects of this process in detail, Williams says, is being able to resolve many individual stars in galaxies to create an accurate picture of their evolution.

Williams’ results will appear in the January 20, 2010 issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

Source: HubbleSite