[/caption]

Officials from Namibia have been examining a hollow ball that fell from the sky back in November 2011. So far, they haven’t had much luck identifying it, so have called in NASA and ESA, hoping the space agencies can provide some answers. The spherical object has a circumference of 1.1 meters (43 inches) and was found in a remote area in the northern part of the country, about 750 kilometers (480 miles) from the capital Windhoek, according to police forensics director Paul Ludik, quoted in an article by AFP.

Ludik described it as made of a “metal alloy known to man” (so cross alien spacecraft part off the list), weighing six kilograms (13 pounds).

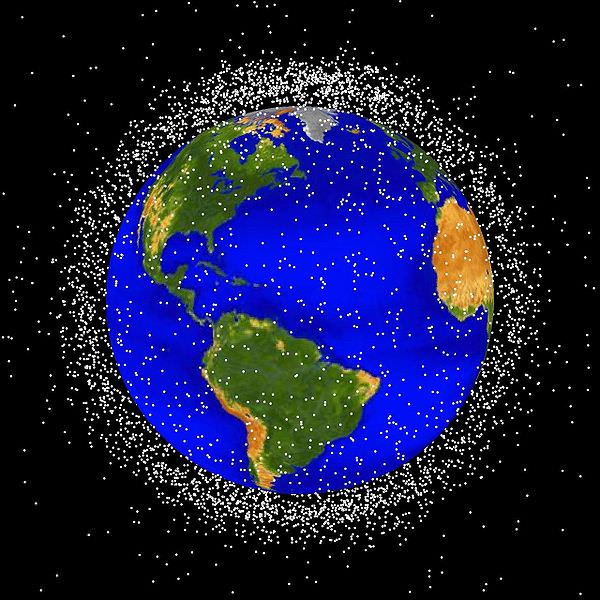

This isn’t the first time balls from space have dropped in on unsuspecting countries.

Back in 2008 spherical objects fell to Brazil and Australia, and there have been previous reports of similar objects, as well.

After some post-crash forensics, the two objects in 2008 were identified the as a Composite Overwrapped Pressure Vessel (or COPV), which were carried on the space shuttles, and are a high pressure container for inert gases. COPVs have been used for a variety of space missions.

They are built with a carbon fiber or Kevlar overcoat to provide reinforcement against the vast pressure gradient between the inside and outside of the container, and so can survive re-entry through Earth’s atmosphere.

The one in Namibia was found 18 meters from its landing spot – it created a mini-crater 33 centimeters deep and 3.8 meters wide.

Other suggestions of what the object could be is a piece from a space gyroscope, a satellite part, a tank from one of the Apollo missions, or a part of a Russian spacecraft, (which have been known to crash to the ground, as well)

Sources: PhysOrg, NASA, and thanks to Ian O’Neill for his previous and current articles on this subject