[/caption]

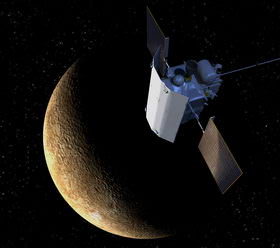

In a case of being in the right place at the right time, the MESSENGER spacecraft was able to capture a average-sized solar flare, allowing astronomers to study high-energy solar neutrons at less than 1 astronomical unit (AU) from the sun for the first time. When the flare erupted on Dec. 31, 2007, MESSENGER – on course for entering orbit around Mercury — was flying at about half an AU, said William C. Feldman, a scientist at the Planetary Science Institute. Previously, only the neutron bursts from the most powerful solar flares have been recorded on neutron spectrometers on Earth or in near-Earth orbit. The MESSENGER results help solve a mystery of why some coronal mass ejections produce almost no energetic protons that reach the Earth, while others produce huge amounts.

Solar flares spew high-energy neutrons into interplanetary space. Typically, these bursts last about 50 to 60 seconds at the sun. But MESSENGER’s Neutron Spectrometer was able to record neutrons from this flare over a period of six to ten hours. “What that’s telling us is that at least some moderate-sized flares continuously produce high-energy neutrons in the solar corona.” Said Feldman. “From this fact, we inferred the continuous production of protons in the 30-to-100-MeV (million electron volt) range due to the flare.”

About 90 percent of all ions produced by a solar flare remain locked to the sun on closed magnetic lines, but another population results from the decay of the neutrons near the sun. This second population of decayed neutrons forms an extended seed population in interplanetary space that can be further accelerated by the massive shock waves produced by the flares, Feldman said.

“So the important results are that perhaps after many flare events two things may occur: continuous production of neutrons over an extended period of time and creation of seed populations of neutrons near the sun that have decayed into protons,” Feldman said. “When coronal mass ejections (nuclear explosions in the corona) send shock waves into space, these feedstock protons are accelerated into interplanetary space.”

“There has always been the question of why some coronal mass ejections produce almost no energetic protons that reach the Earth, while others produce huge amounts,” he added. “It appears that these seed populations of energetic protons near the sun could provide the answer, because it’s easier to accelerate a proton that already has an energy of 1 MeV than a proton that is at 1 keV (the solar wind).”

The seed populations are not evenly distributed, Feldman said. Sometimes they’re in the right place for the shock waves to send them toward Earth, while at other times they’re in locations where the protons are accelerated in directions that don’t take them near Earth.

The radiation produced by solar flares is of more than academic interest to NASA, Feldman added. Energetic protons from solar flares can damage Earth-orbiting satellites and endanger astronauts on the International Space Station or on missions to the Moon and Mars.

“People in the manned spaceflight program are very interested in being able to predict when a coronal mass ejection is going to be effective in generating dangerous levels of high-energy protons that produce a radiation hazard for astronauts,” he said.

To do this, scientists need to know a lot more about the mechanisms that produce flares and which flare events are likely to be dangerous. At some point they hope to be able to predict space weather — where precipitation is in the form of radiation — with the same accuracy that forecasters predict rain or snow on Earth.

MESSENGER could provide significant data toward this goal, Feldman observed. “What we saw and published is what we hope will be the first of many flares we’ll be able to follow through 2012,” he said. “The beauty of MESSENGER is that it’s going to be active from the minimum to the maximum solar activity during Solar Cycle 24, allowing us to observe the rise of a solar cycle much closer to the sun than ever before.”

MESSENGER is currently orbiting the sun between 0.3 and 0.6 AU — (an AU is the average distance between the Earth and the sun, or about 150,000 km) — on its way to orbit insertion around Mercury in March 2011. At Mercury, it will be within 0.45 AU of the sun for one Earth year.

Read the team’s paper: Evidence for Extended Acceleration of Solar Flare Ions from 1-8-MeV Solar Neutrons Detected with the MESSENGER Neutron Spectrometer.

Source: PSI