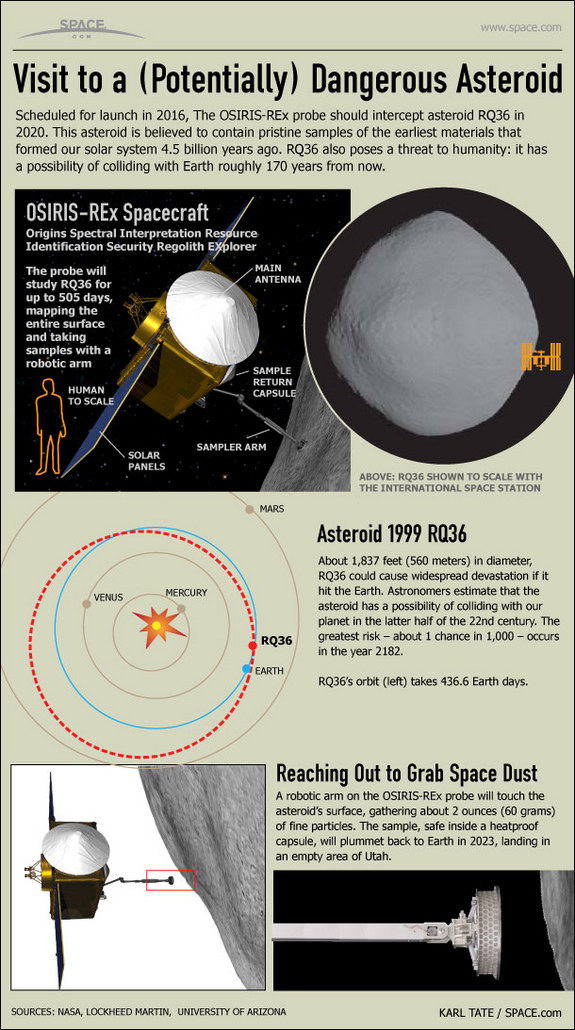

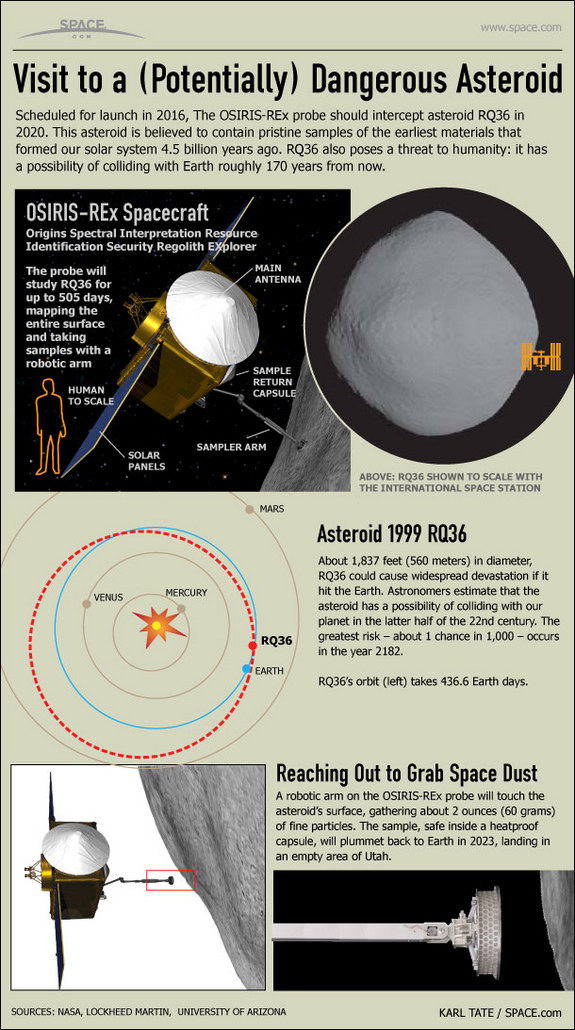

Thanks to Space.com and the Tech Media Network for sharing this infographic showing how NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission will reach out and grab a sample from asteroid RQ26 in 2020. Source SPACE.com:

Source SPACE.com.

Thanks to Space.com and the Tech Media Network for sharing this infographic showing how NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission will reach out and grab a sample from asteroid RQ26 in 2020. Source SPACE.com:

Source SPACE.com.

[/caption]

Scientists from Japan were given the go-ahead to retrieve the sample return capsule from the Hayabusa spacecraft, which is hoped to contain the first piece of asteroid ever brought to Earth, perhaps providing insight into the origins of asteroids – and our universe. The capsule was ejected three hours before reaching Earth, and the sample canister descended through Earth’s atmosphere, preceding the spacecraft which broke up in spectacular fashion (click here to see the video) over the Australian Outback. The capsule lay in the Woomera Prohibited Area until morning when Aboriginal elders deemed it had not landed in any indigenous sacred sites, giving the OK for the scientists to retrieve it.

The insulated and cushioned re-entry capsule, 40 cm in diameter and 25 cm deep has a mass of about 20 kg. The capsule had a convex nose covered with a 3 cm thick ablative heat shield to protect the samples from the high velocity (~13 km/s) re-entry.

Apparently, it landed right on target. The director of the Woomera test range, Doug Gerrie, said the probe had completed a textbook landing in the South Australian desert. “They landed it exactly where they nominated they would.

The capsule will remain sealed until it arrives at the JAXA facility near Tokyo, and may remain unopened for weeks as it undergoes testing.

The mission launched in 2003, and endured a series of technical glitches over its five-billion-kilometer (three-billion-mile) journey to the asteroid Itokawa and back. A large solar flare in late 2003 “injured” the solar panels, providing less power to Hayabusa’s ion engines, delaying the rendezvous with the asteroid. Then, as the spacecraft approached Itokawa, Hayabusa lost the use of its Y-axis reaction wheel. While it flew near the asteroid and sent back data, scientists and engineers aren’t sure if the spacecraft was successful in obtaining samples, as while it appears Hayabusa landed briefly, it is not certain the “bullets” fired to stir up dust for the container to capture. The return to Earth was delayed by three years from more thruster and navigational failures, but the JAXA team nursed and coaxed the spacecraft back home to a spectacular return. There was concern that the parachute batteries may be been depleted due to the extra time it took to get back to Earth, but obviously they worked quite well.

Sources: JAXA, NASA, AFP

[/caption]

After overcoming multiple serious glitches, and a three-year delay in its four billion miles (six billion kilometers) round-trip journey, JAXA’s Hayabusa spacecraft is expected to land in Australia around 14:00 UTC on Sunday, June 13; (midnight local time in Australia, 11 pm in Japan and 11:00 a.m. ET in the US). Scientists and space enthusiasts alike are hoping there is some precious cargo aboard in the sample return capsule: dust from an asteroid.

The latest word from JAXA, as of this writing, is that all systems were doing well on Hayabusa. The teams assessed the trajectory of Hayabusa and confirmed that everything was nominal.

If all goes well, Hayabusa will release a canister that will land in the Woomera Prohibited Area in the outback of South Australia; Hayabusa itself will follow, putting on a show over Australia as it breaks up and incinerates in Earth’s atmosphere.

You can follow the landing in several ways. A NASA team will be attempting to observe the re-entry of Hayabusa in a DC-8 plane, and they hope to have a webcast at this link.

There will be a “Hayabusa Live” website and a Hayabusa blog will be updated frequently, plus this Hayabusa Twitter feed.

Here’s a link to a finder chart and more from Paul Floyd at his website, Night Sky Online.

The Hayabusa spacecraft, formerly known as MUSES-C launched on May 9, 2003 and rendezvoused with the asteroid Itokawa in mid-September 2005. Hayabusa studied the asteroid’s shape, spin, topography, color, composition, density, and history. Then in November 2005, it attempted to land on the asteroid to collect samples but failed to do so. However, it is hoped that some dust swirled into the sampling chamber. You can listen to Universe Today writer Steve Nerlich (from Cheap Astronomy) tell the story of Hayabusa’s trials and tribulations on this 365 Days of Astronomy podcast.

The aim of the $200 million Hayabusa project was to learn more about asteroids and to help in our understanding of the origin and evolution of the solar system.

If Hayabusa is indeed carrying samples from the asteroid, it would be only the fourth sample return of space material in history — including the moon matter collected by the Apollo missions, comet matter by Stardust and solar matter in the Genesis mission.

We’re all hoping for the best for this first sample return from an asteroid, and it should be an interesting time in Australia. Dozens of scientists will be watching and waiting to see the return.

Plus, as Col Maybury from radio station 2NUR in Australia tells me, all traffic around the area will be stopped, including the Ghan train, one of the world’s great trains that travels from south to north across the continent of Australia, and it happens to be passing through Woomera right at the time Hayabusa should be returning. Col said he called the train company, and was told that the train engineers are to keep a look out for the entry trail.

“So a mighty train named after Afghan camel drivers may have to halt for a small spacecraft or be hit by a flying object,” Col wrote me in an email. He will have a live report on Radio 2NUR-FM on Tuesday the 15th at 10:20 am in Newcastle, 12:20 GMT, talking with the Woomera officials for a follow-up of the Hayabusa event.

Preliminary analysis of the samples will be carried out by the team in Japan, but after one year scientists around the world can apply for access to bits of the asteroid material for research.