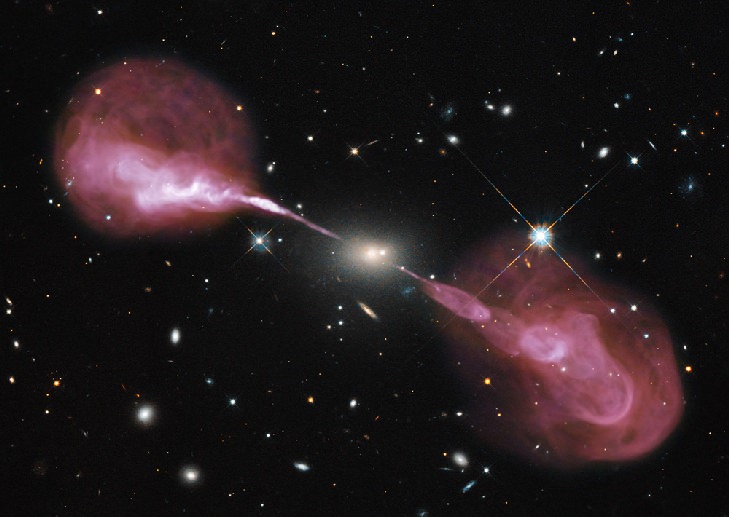

It’s long been a mystery for astronomers: why aren’t galaxies bigger? What regulates their rates of star formation and keeps them from just becoming even more chock-full-of-stars than they already are? Now, using a worldwide network of radio telescopes, researchers have observed one of the processes that was on the short list of suspects: one supermassive black hole’s jets are plowing huge amounts of potential star-stuff clear out of its galaxy.

Astronomers have theorized that many galaxies should be more massive and have more stars than is actually the case. Scientists proposed two major mechanisms that would slow or halt the process of mass growth and star formation — violent stellar winds from bursts of star formation and pushback from the jets powered by the galaxy’s central, supermassive black hole.

Read more: Our Galaxy’s Supermassive Black Hole is a Sloppy Eater

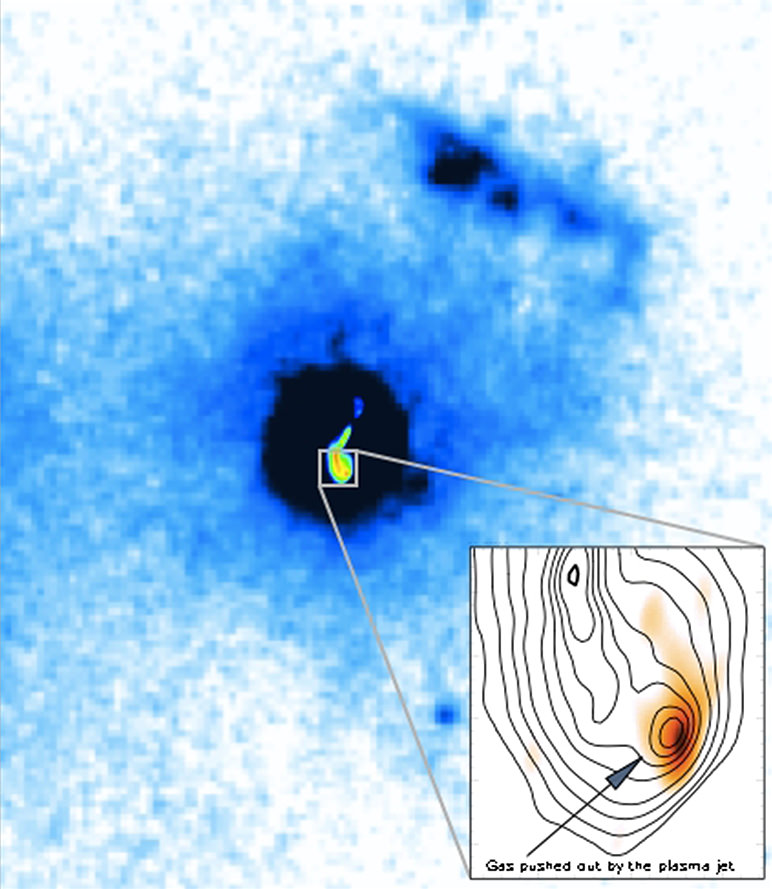

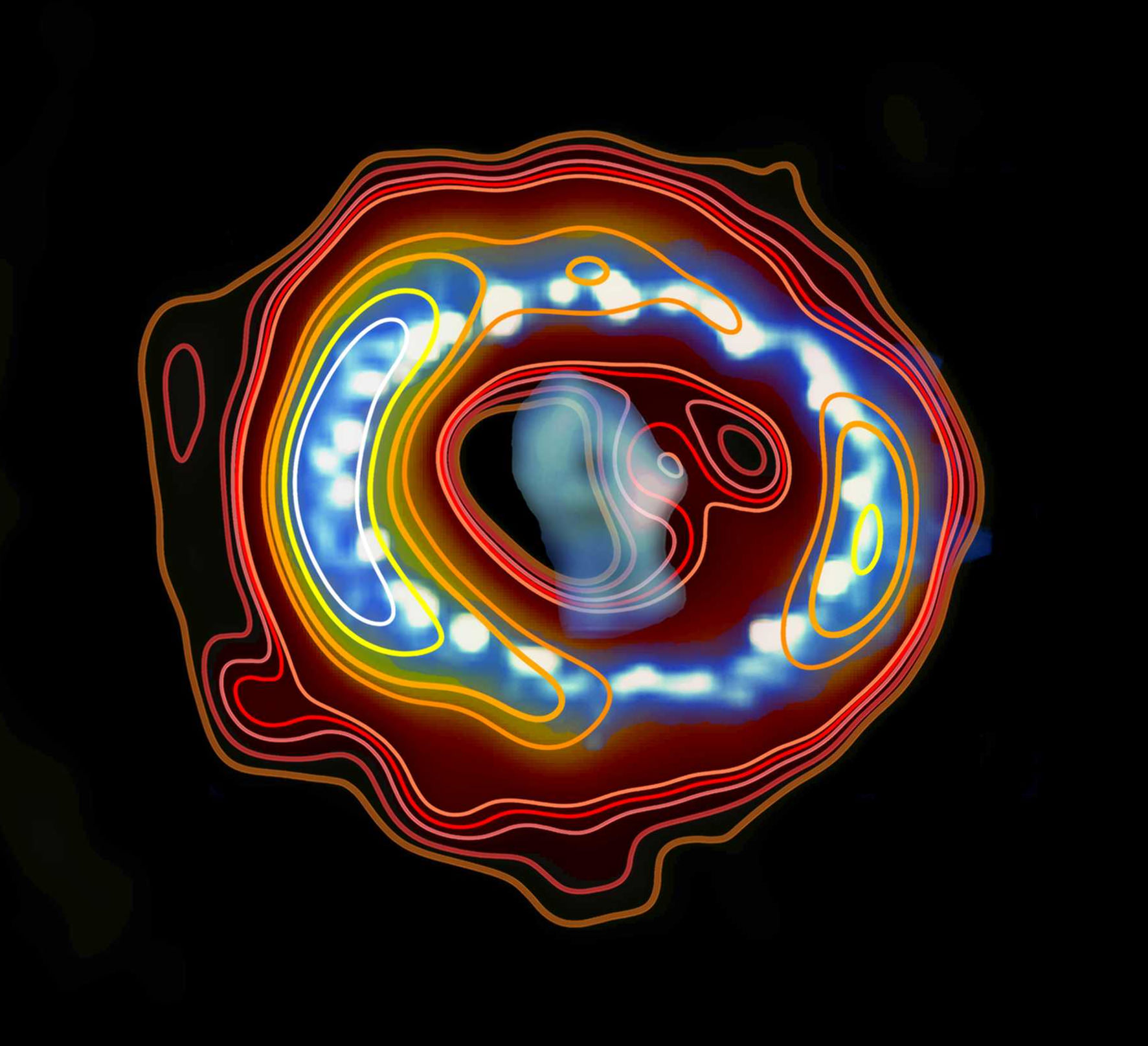

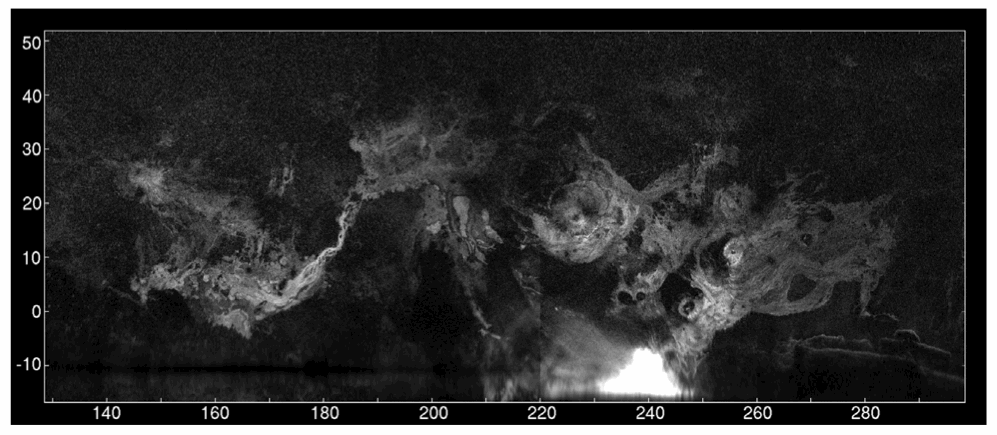

“With the finely-detailed images provided by an intercontinental combination of radio telescopes, we have been able to see massive clumps of cold gas being pushed away from the galaxy’s center by the black-hole-powered jets,” said Raffaella Morganti, of the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy and the University of Groningen.

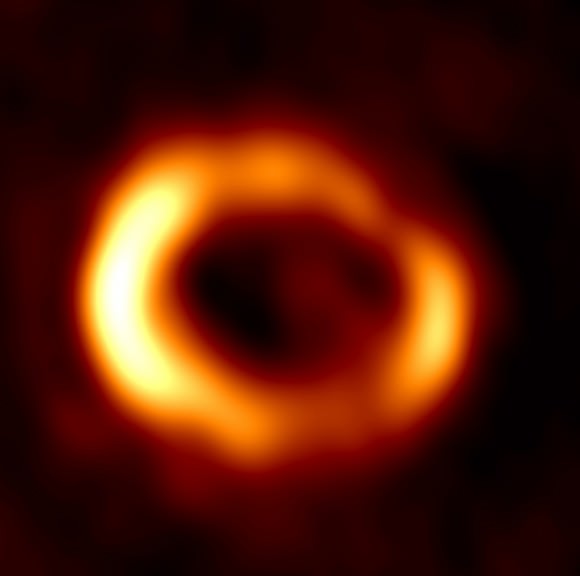

The scientists studied a galaxy called 4C12.50, nearly 1.5 billion light-years from Earth. They chose this galaxy because it is at a stage where the black-hole “engine” that produces the jets is just turning on. As the black hole, a concentration of mass so dense that not even light can escape, pulls material toward it, the material forms a swirling disk surrounding the black hole. Processes in the disk tap the tremendous gravitational energy of the black hole to propel material outward from the poles of the disk.

At the ends of both jets, the researchers found clumps of hydrogen gas moving outward from the galaxy at 1,000 kilometers per second. One of the clouds has much as 16,000 times the mass of the Sun, while the other contains 140,000 times the mass of the Sun.

The larger cloud, the scientists said, is roughly 160 by 190 light-years in size.

“This is the most definitive evidence yet for an interaction between the swift-moving jet of such a galaxy and a dense interstellar gas cloud,” Morganti said. “We believe we are seeing in action the process by which an active, central engine can remove gas — the raw material for star formation — from a young galaxy,” she added.

The researchers published their findings in the September 6 issue of the journal Science.

Source: NRAO press release