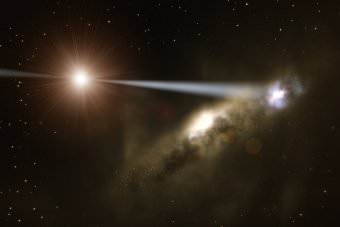

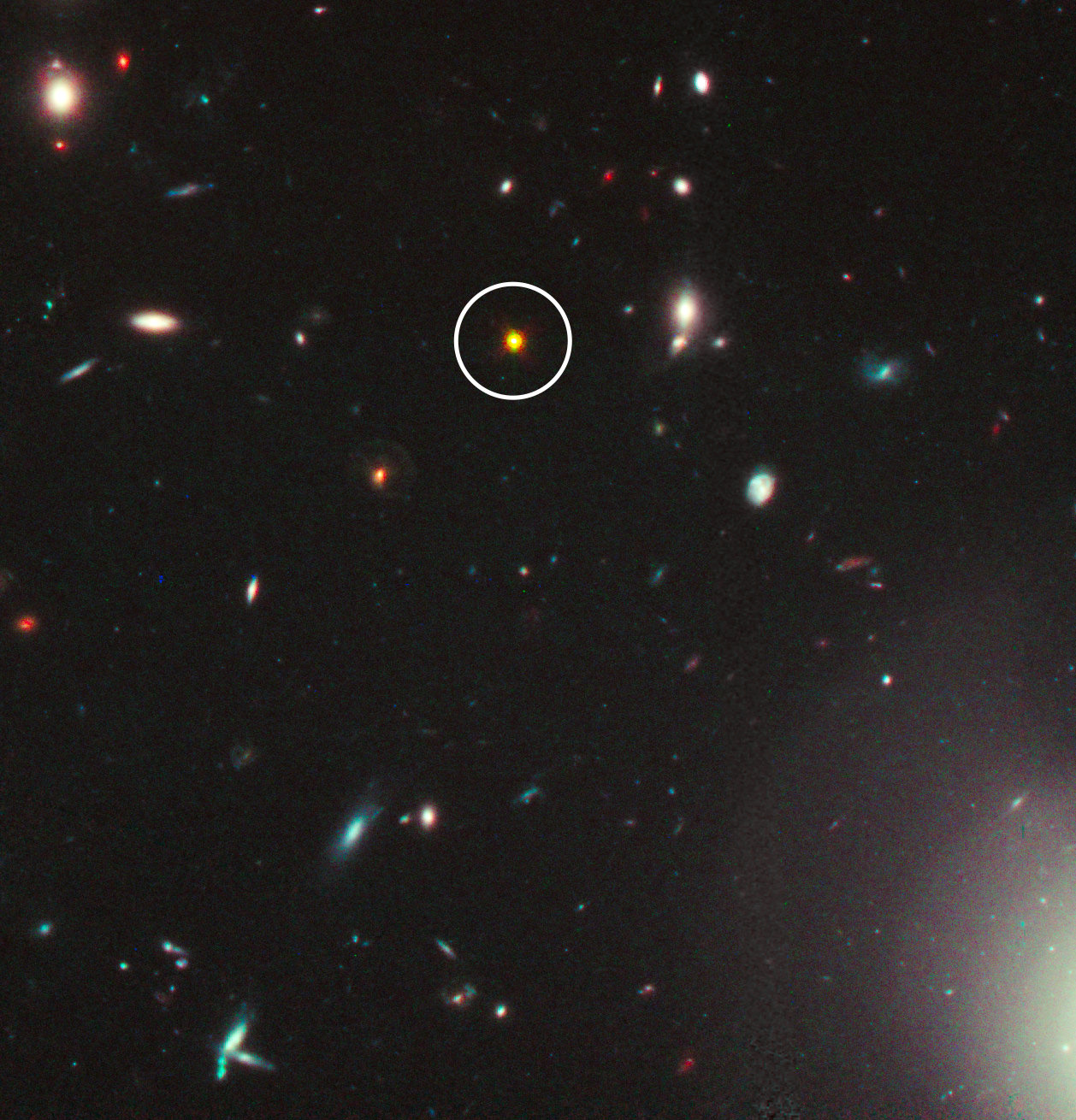

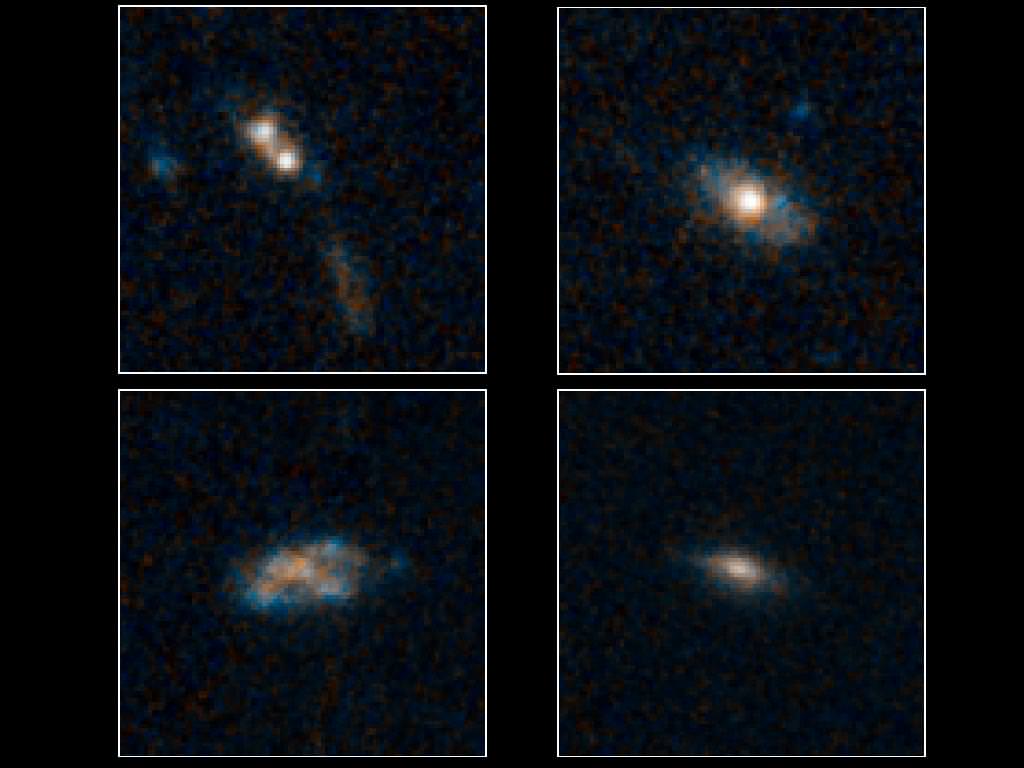

Black holes one billion times the Sun’s mass or more lie at the heart of many galaxies, driving their evolution. Although common today, evidence of supermassive black holes existing since the infancy of the Universe, one billion years or so after the Big Bang, has puzzled astronomers for years.

How could these giants have grown so massive in the relatively short amount of time they had to form? A new study led by Tal Alexander from the Weizmann Institute of Science and Priyamvada Natarajn from Yale University, may provide a solution.

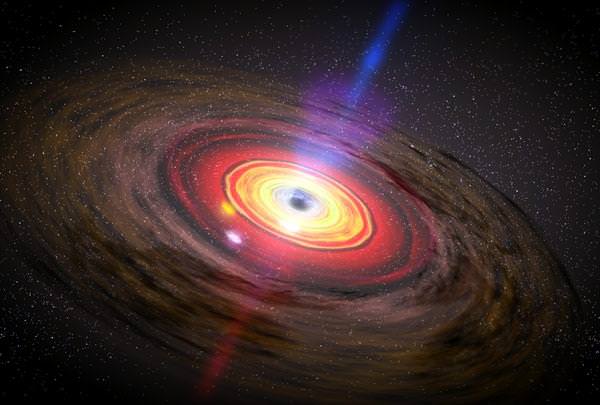

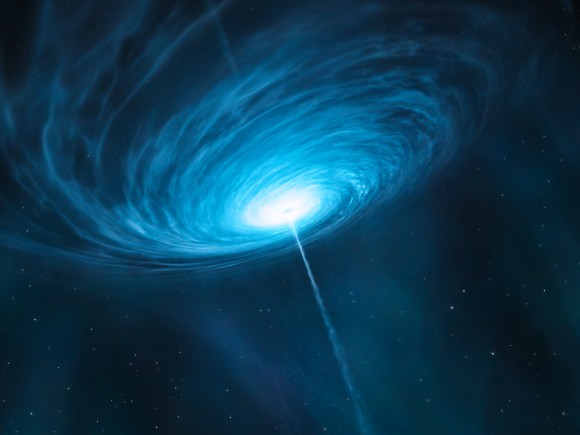

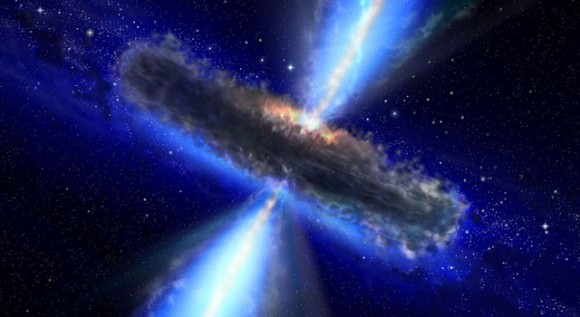

Black holes are often mistaken to be monstrous creatures that suck in dust and gas at an enormous rate. But this couldn’t be further from the truth (in fact the words “suck” and “black hole” in the same sentence makes me cringe). Although they typically accumulate bright accretion disks — swirling disks of gas and dust that make them visible across the observable Universe — these very disks actually limit the speed of growth.

First, as matter in an accretion disk gets close to the black hole, traffic jams occur that slow down any other infalling material. Second, as matter collides within these traffic jams, it heats up, generating energy radiation that actually drives gas and dust away from the black hole.

A star or a gas stream can actually be on a stable orbit around the black hole, much as a planet orbits around a star. So it is quite a challenge for astronomers to think of ways that would make a black hole grow to supermassive proportions.

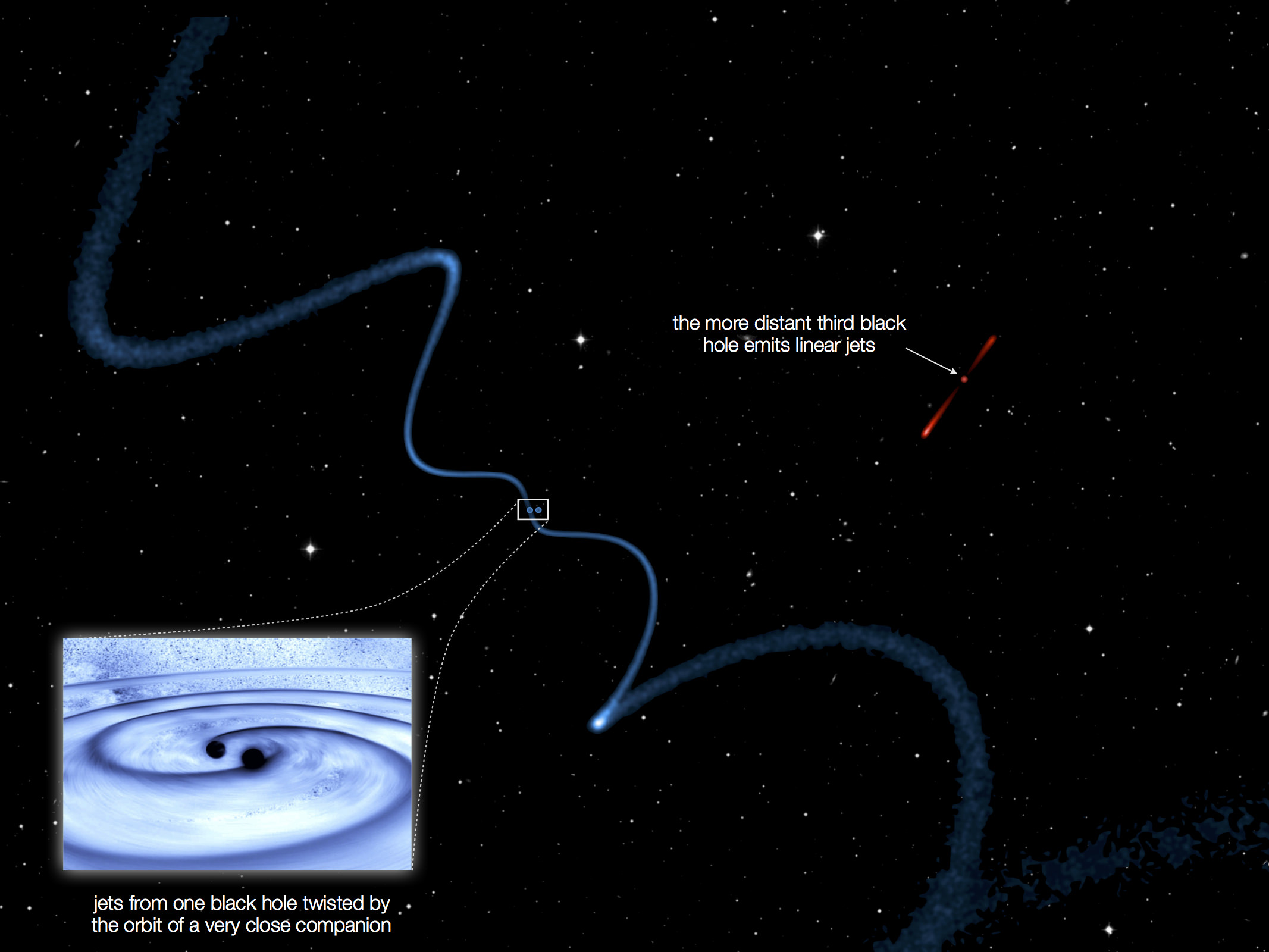

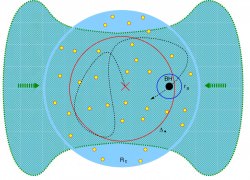

Luckily, Alexander and Natarajan may have found a way to do this: by placing the black hole within a cluster of thousands of stars, they’re able to operate without the restrictions of an accretion disk.

Black holes are generally thought to form when massive stars, weighing tens of solar masses, explode after their nuclear fuel is spent. Without the nuclear furnace at its core pushing against gravity, the star collapses. While the inner layers fall inward to form a black hole of only about 10 solar masses, the outer layers fall faster, hitting the inner layers, and rebounding in a huge supernova explosion. At least that’s the simple version.

The team began with a model of a black hole, created from this stellar blast, embedded within a cluster of thousands of stars. A continuous flow of dense, cold, opaque gas fell into the black hole. But here’s the trick: the gravitational pull of many nearby stars caused it to zigzag randomly, preventing it from forming an accretion disk.

Without an accretion disk, not only is matter more able to fall into the black hole from all sides, but it isn’t slowed down in the accretion disk itself.

All in all, the model suggests that a black hole 10 times the mass of the Sun could grow to more than 10 billion times the mass of the Sun by one billion years after the Big Bang.

The paper was published Aug. 7 in Science and is available online.