Throughout Earth’s history, the planet’s surface has been regularly impacted by comets, meteors, and the occasional large asteroid. While these events were often destructive, sometimes to the point of triggering a mass extinction, they may have also played an important role in the emergence of life on Earth. This is especially true of the Hadean Era (ca. 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago) and the Late Heavy Bombardment, when Earth and other planets in the inner Solar System were impacted by a disproportionately high number of asteroids and comets.

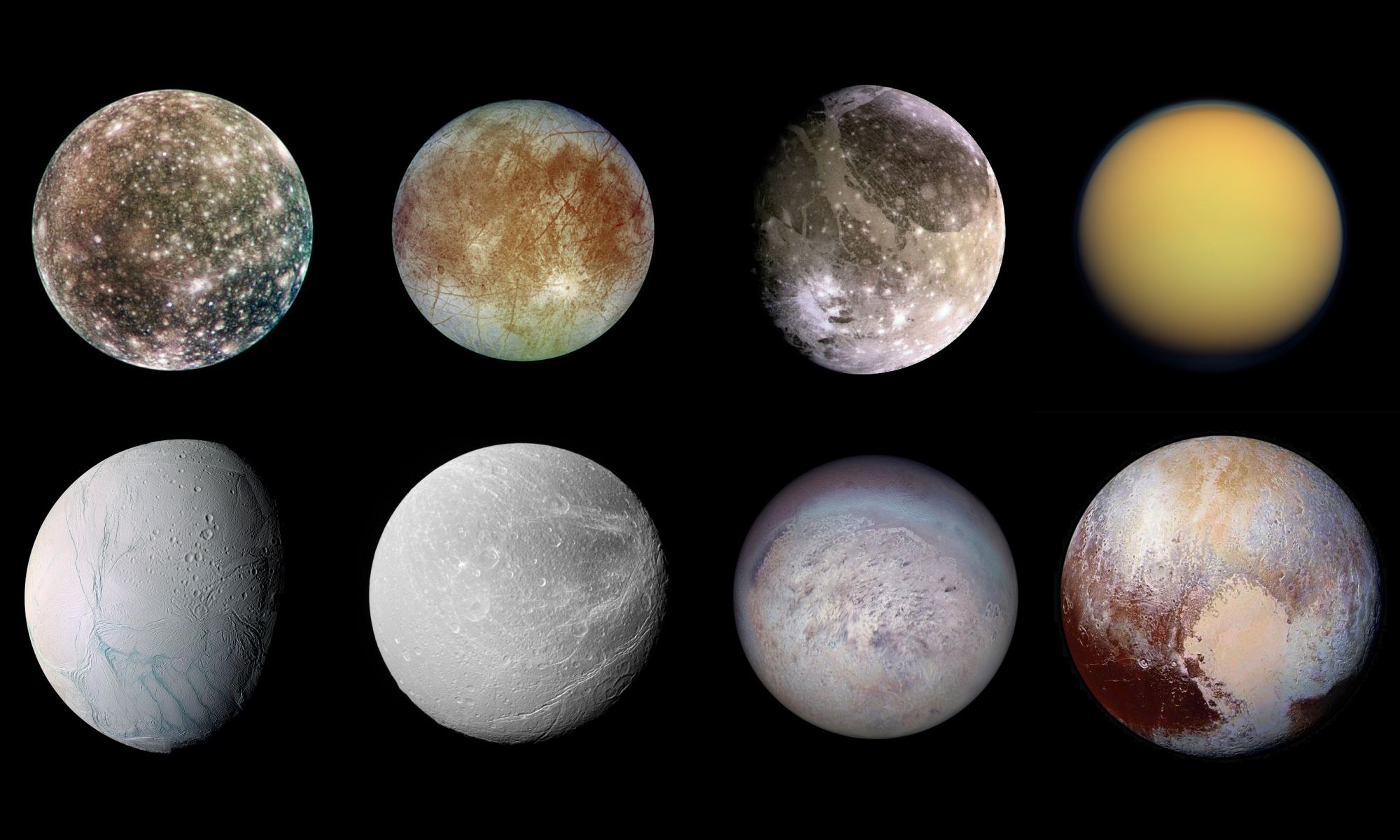

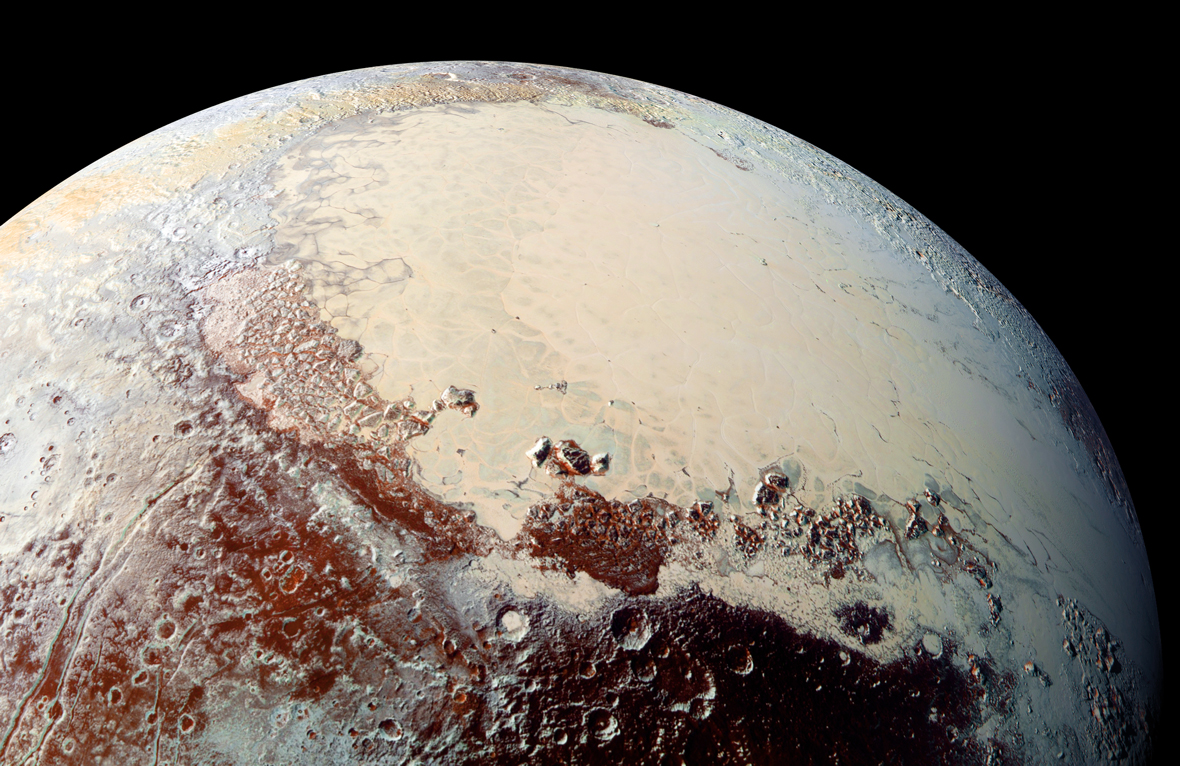

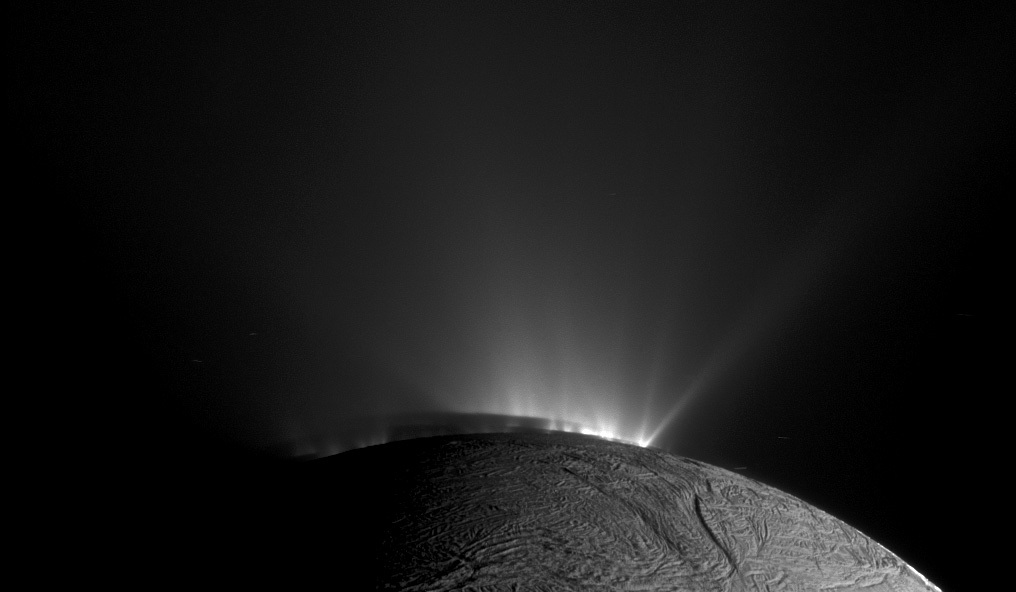

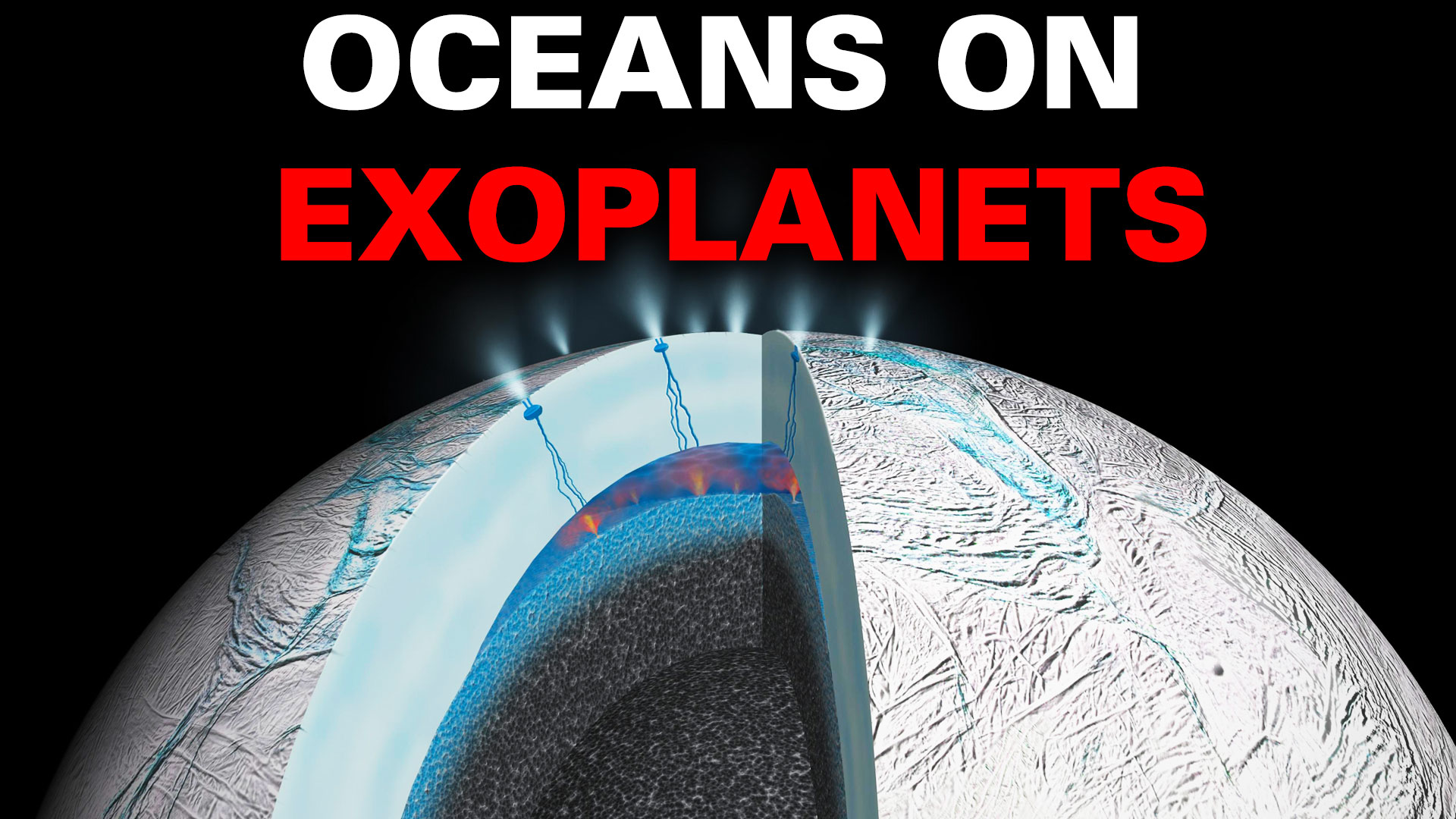

These impactors are thought to have been how water was delivered to the inner Solar System and possibly the building blocks of life. But what of the many icy bodies in the outer Solar System, the natural satellites that orbit gas giants and have liquid water oceans in their interiors (i.e., Europa, Enceladus, Titan, and others)? According to a recent study led by researchers from Johns Hopkins University, impact events on these “Ocean Worlds” could have significantly contributed to surface and subsurface chemistry that could have led to the emergence of life.

Continue reading “Could Comets have Delivered the Building Blocks of Life to “Ocean Worlds” like Europa, Enceladus, and Titan too?”