It’s one of the most intense and violent of all events in space – a supernova. Now a team of researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics have been taking a very specialized look at the formation of neutron stars at the center of collapsing stars. Through the use of sophisticated computer simulations, they have been able to create three-dimensional models which show the physical effects – intense and violent motions which occur when stellar matter is drawn inward. It’s a bold, new look into the dynamics which happen when a star explodes.

As we know, stars which have eight to ten times the mass of the Sun are destined to end their lives in a massive explosion, the gases blown into space with incredible force. These cataclysmic events are among the brightest and most powerful events in the Universe and can outshine a galaxy when they occur. It is this very process which creates elements critical to life as we know it – and the beginnings of neutron stars.

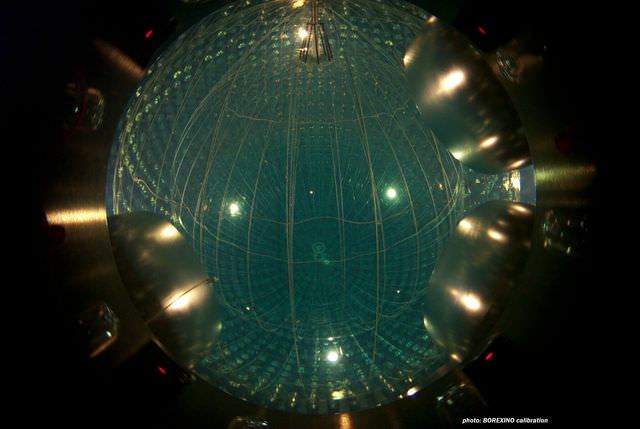

Neutron stars are an enigma unto themselves. These highly compact stellar remnants contain as much as 1.5 times the mass of the Sun, yet are compressed to the size of a city. It is not a slow squeeze. This compression happens when the stellar core implodes from the intense gravity of its own mass… and it takes only a fraction of a second. Can anything stop it? Yes. It has a limit. Collapse ceases when the density of the atomic nuclei is exceeded. That’s comparable to around 300 million tons compressed into something the size of a sugar cube.

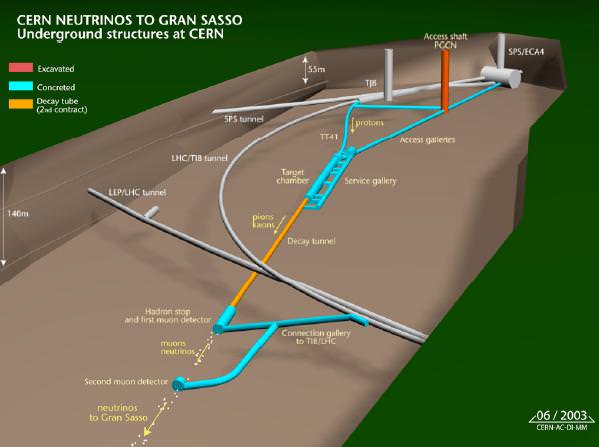

Studying neutron stars opens up a whole new dimension of questions which scientists are keen to answer. They want to know what causes stellar disruption and how can the implosion of the stellar core revert to an explosion. At present, they theorize that neutrinos may be a critical factor. These tiny elemental particles are created and expelled in monumental numbers during the supernova process and may very well act as heating elements which ignite the explosion. According to the research team, neutrinos could impart energy into the stellar gas, causing it to build up pressure. From there, a shock wave is created and as it speeds up, it could disrupt the star and cause a supernova.

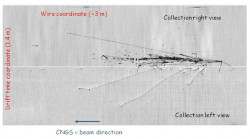

As plausible as it might sound, astronomers aren’t sure if this theory could work or not. Because the processes of a supernova cannot be recreated under laboratory conditions and we’re not able to directly see into the interior of a supernovae, we’ll just have to rely on computer simulations. Right now, researchers are able to recreate a supernova event with complex mathematical equations which replicate the motions of stellar gas and the physical properties which happen at the critical moment of core collapse. These types of computations require the use of some of the most powerful supercomputers in the world, but it has also been possible to use more simplified models to get the same results. “If, for example, the crucial effects of neutrinos were included in some detailed treatment, the computer simulations could only be performed in two dimensions, which means that the star in the models was assumed to have an artificial rotational symmetry around an axis.” says the research team.

With the support of the Rechenzentrum Garching (RZG), scientists were able to create in a singularly efficient and fast computer program. They were also given access to most powerful supercomputers, and a computer time award of nearly 150 million processor hours, which is the greatest contingent so far granted by the “Partnership for Advanced Computing in Europe (PRACE)” initiative of the European Union, the team of researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics (MPA) in Garching could now for the first time simulate the processes in collapsing stars in three dimensions and with a sophisticated description of all relevant physics.

“For this purpose we used nearly 16,000 processor cores in parallel mode, but still a single model run took about 4.5 months of continuous computing”, says PhD student Florian Hanke, who performed the simulations. Only two computing centers in Europe were able to provide sufficiently powerful machines for such long periods of time, namely CURIE at Très Grand Centre de calcul (TGCC) du CEA near Paris and SuperMUC at the Leibniz-Rechenzentrum (LRZ) in Munich/Garching.

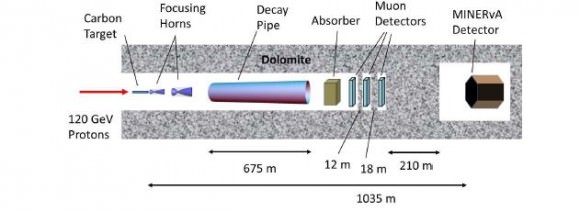

“My colleague Thierry Foglizzo at the Service d’ Astrophysique des CEA-Saclay near Paris has obtained a detailed understanding of the growth conditions of this instability”, explains Hans-Thomas Janka, the head of the research team. “He has constructed an experiment, in which a hydraulic jump in a circular water flow exhibits pulsational asymmetries in close analogy to the shock front in the collapsing matter of the supernova core.” Known as Shallow Water Analogue of Shock Instability, the dynamic process can be demonstrated in less technicalized manners by eliminating the important effects of neutrino heating – a reason which causes many astrophysicists to doubt that collapsing stars might go through this type of instability. However, the new computer models are able to demonstrate the Standing Accretion Shock Instability is a critical factor.

“It does not only govern the mass motions in the supernova core but it also imposes characteristic signatures on the neutrino and gravitational-wave emission, which will be measurable for a future Galactic supernova. Moreover, it may lead to strong asymmetries of the stellar explosion, in course of which the newly formed neutron star will receive a large kick and spin”, describes team member Bernhard Müller the most significant consequences of such dynamical processes in the supernova core.

Are we finished with supernova research? Do we understand everything there is to know about neutron stars? Not hardly. At the present time, the scientist are ready to further their investigations into the measurable effects connected to SASI and refine their predictions of associated signals. In the future they will further their understanding by performing more and longer simulations to reveal how instability and neutrino heating react together. Perhaps one day they’ll be able to show this relationship to be the trigger which ignites a supernova explosion and conceives a neutron star.

Original Story Source: Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics News Release.