Host: Fraser Cain (@fcain)

Astrojournalist: Morgan Rehnberg (cosmicchatter.org / @cosmic_chatter)

This Week’s Stories:

Continue reading “Weekly Space Hangout – February 21, 2014: Two-Man Show!”

Host: Fraser Cain (@fcain)

Astrojournalist: Morgan Rehnberg (cosmicchatter.org / @cosmic_chatter)

This Week’s Stories:

Continue reading “Weekly Space Hangout – February 21, 2014: Two-Man Show!”

If the dataset from the Kepler mission is any indication, the most common type of exoplanets in our galaxy aren’t Earth-sized rocky worlds or hot Jupiters. In fact, the most common type of exoplanet isn’t one that we see in our own neighborhood at all.

“Perhaps the most remarkable discovery by Kepler is the amount of planets between the size of Earth to four times the size of Earth,” said Geoff Marcy, professor of astronomy at University of California, speaking at the American Astronomical Society meeting this week in Washington D.C. “This is a size range that dominates the planet inventory from Kepler and it a size range not represented in our own Solar System. We don’t know for sure what these planets are made of and we don’t know how they form.”

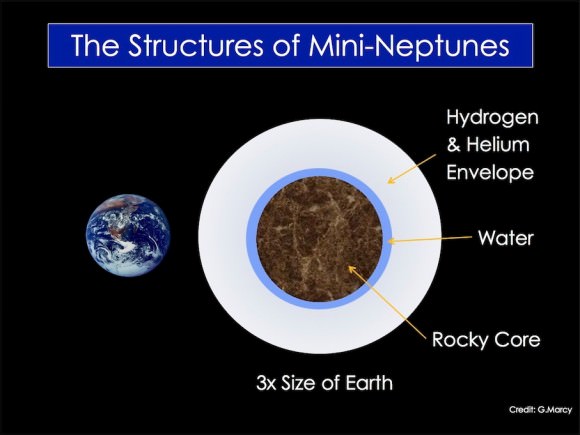

These “mini-Neptunes” as Marcy called them, represent a huge sample in the Kepler data; about 75% of the planets found by Kepler vary in size between the Earth and Neptune, and for four years since the Kepler data have been rolling in, scientists have been trying to understand these planets.

“There’s been an enormous amount of measurements and quantitative work by the NASA Ames Kepler team,” Marcy said.

While masses and planet densities emerged from the work, astronomers still aren’t certain how they form or if they are made of rock, water or gas.

The team focused on about 42 of these planets. Two planets highlighted by Marcy in his presentation are thought to be rocky, and are named Kepler-99b and Kepler-406b. Both are forty percent larger in size than Earth and have a density similar to lead. The planets orbit their host stars in less than five and three days respectively, making these worlds too hot for life as we know it.

The team used Doppler measurements of the planets’ host stars to measure the reflex wobble of the host star, caused by the gravitational tug on the star exerted by the orbiting planet. The measured wobble reveals the mass of the planet: the higher the mass of the planet, the greater the gravitational tug on the star and hence the greater the wobble.

They also the measured transit timing variations (TTV) to determine how much neighboring planets can tug on one another causing one planet to accelerate and another planet to decelerate along its orbit.

These measurements allow for computing mass and densities of the planets, as well as figuring out the possible chemical composition of these worlds. The majority of the measurements suggest that the mini-Neptunes have a rocky core but some may have a gaseous outer shell of hydrogen or helium. Some might just be rocky with no outer envelope at all.

“What we think is happening is that some of these planets may have water on top of a rocky core,” Marcy said. “Larger planets might have the same rocky core with added gas. That’s how you get planets measuring from 1 to 4 earth radii. The planets with lower densities imply increasing amounts of gas on top of a rocky core.”

“Kepler’s primary objective is to determine the prevalence of planets of varying sizes and orbits. Of particular interest to the search for life is the prevalence of Earth-sized planets in the habitable zone,” said Natalie Batalha, Kepler mission scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center. “But the question in the back of our minds is: are all planets the size of Earth rocky? Might some be scaled-down versions of icy Neptunes or steamy water worlds? What fraction are recognizable as kin of our rocky, terrestrial globe?”

The team said that the mass measurements produced by Doppler and TTV will help to answer these questions. The results hint that a large fraction of planets smaller than 1.5 times the radius of Earth may be comprised of the silicates, iron, nickel and magnesium that are found in the terrestrial planets here in the Solar System.

Armed with this type of information, scientists will be able to turn the fraction of stars harboring Earth-sizes planets into the fraction of stars harboring bona-fide rocky planets. And that’s a step closer to finding a habitable environment beyond the Solar System.

Marcy added later in the discussion that there’s one type of telescope that would most helpful: a Terrestrial Planet Finder type mission that would measure the temperature, size, and the orbital parameters of planets as small as our Earth in the habitable zones of distant solar systems. Alas, TPF was canceled.

Read more about the study of mini-Neptunes here.

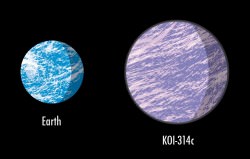

Gas planets aren’t always bloated, monstrous worlds the size of Jupiter or Saturn (or larger) they can also apparently be just barely bigger than Earth. This was the discovery announced earlier today during the 223rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Washington, DC, when findings regarding the gassy (but surprisingly small) exoplanet KOI-314c were presented.

“This planet might have the same mass as Earth, but it is certainly not Earth-like,” said David Kipping of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), lead author of the discovery. “It proves that there is no clear dividing line between rocky worlds like Earth and fluffier planets like water worlds or gas giants.”

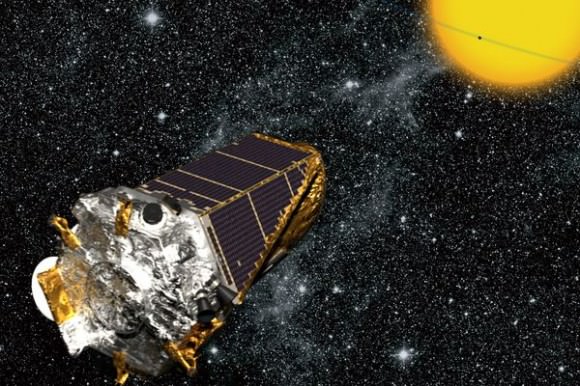

Discovered by the Kepler space telescope — ironically, during a hunt for exomoons — KOI-314c was found transiting a red dwarf star only 200 light-years away — “a stone’s throw by Kepler’s standards,” according to Kipping. (Kepler’s observation depth is about 3000 light-years.)

Kipping used a technique called transit timing variations (TTV) to study two of three exoplanets found orbiting KOI-314. Both are about 60% larger than Earth in diameter but their respective masses are very different. KOI-314b is a dense, rocky world four times the mass of Earth, while KOI-314c’s lighter, Earthlike mass indicates a planet with a thick “puffy” atmosphere… similar to what’s found on Neptune or Uranus.

Unlike those chilly worlds, though, this newfound exoplanet turns up the heat. Orbiting its star every 23 days, temperatures on KOI-314c reach 220ºF (104ºC)… too hot for water to exist in liquid form and thus too hot for life as we know it.

In fact Kipping’s team found KOI-314c to only be 30 percent denser than water, suggesting that it has a “significant atmosphere hundreds of miles thick,” likely composed of hydrogen and helium.

It’s thought that KOI-314c may have originally been a “mini-Neptune” gas planet and has since lost some of its atmosphere, boiled off by the star’s intense radiation.

Not only is KOI-314c the lightest exoplanet to have both its mass and diameter measured but it’s also a testament to the success and sensitivity of the relatively new TTV method, which is particularly useful in multiple-planet systems where the tiniest gravitational wobbles reveal the presence and details of neighboring bodies.

(Watch the latest Kepler Orrery video here)

“We are bringing transit timing variations to maturity,” Kipping said. He added during the closing remarks of his presentation at AAS223: “It’s actually recycling the way Neptune was discovered by watching Uranus’ wobbles 150 years ago. I think it’s a method you’ll be hearing more about. We may be able to detect even the first Earth 2.0 Earth-mass/Earth-radius using this technique in the future.”

Host: Fraser Cain

Guests: +Brian Koberlein (@briankoberlein), David Dickinson (@Astroguyz), Pamela Gay (@starstryder)

Big thanks to Nicole Gugliucci (@noisyastronomer) for doing a wonderful job producing this past year!

Continue reading “Weekly Space Hangout – December 27, 2013: Year in Review & Looking Forward”

Exoplanets are really tiny compared to their host star, and it’s hard to imagine sometimes how astronomers can even find one of these worlds — let alone thousands of them. This nifty two-part series from PBS explains how it’s possible in an easy-to-understand and hilarious way. As an example, this is how they describe the Kepler space telescope’s capabilities:

“It can’t actually see those exoplanets because the stars that they surround are so big and bright. Instead, it looks for the tiny shadow of the planet as it passes in front of its parent star. If that sounds hard, that’s because it is. It’s like seeing a flea in a lightbulb in Los Angeles from New York City,” said host Joe Hanson in the video.

Near the end, he provides an interesting segway into the question of life beyond Earth: “The question we’re really interested in is not how common are planets, but how common are we.” That gets tackled in part 2 of the video, which you can see below the jump.

Remember that 2014 will be an interesting year for Kepler as NASA figures out what to do next with the observatory. It isn’t able to perform its primary mission (seeking exoplanets in Cygnus) because two of its four reaction wheels or pointing devices are malfunctioning. NASA, however, has an innovative fix on the books that could allow it to swing different fields of view during the year — check out this infographic for more details.

If you’ve ever wanted to know what 3,538 exoplanets look like spinning around their stars, here you go!

This is the third and latest installment of the mesmerizing Kepler Orrery videos by Daniel Fabrycky from the Kepler science team. It shows the relative sizes of the orbits and planets in the multi-transiting planetary systems discovered by Kepler up to November 2013 (according to the Kepler site, 3,538 candidates so far.) According to Daniel “the colors simply go by order from the star (the most colorful is the 7-planet system KOI-351). The terrestrial planets of the Solar System are shown in gray.”

Not that our Solar System is boring, of course, but well, ya know… there are an awful lot of planets out there.

Check out Daniel’s previous version here.

Last week I held an interview with Dr. Sara Seager – a lead astronomer who has contributed vastly to the field of exoplanet characterization. The condensed interview may be found here. Toward the end of our interview we had a lengthy conversation regarding the future of exoplanet research. I quickly realized that this subject should be an article in itself.

The following is a list of approved missions that will continue the search for habitable worlds, with input from Dr. Seager about their potential for finding planets that might harbor life.

Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS)

Slated to launch in 2017, TESS will search for exoplanets by looking for faint dips in brightness as the unseen planet passes in front of its host star. With a price tag of $200 million, TESS will be the first space-based mission to scan the entire sky for exoplanets.

While the Kepler space telescope confirmed hundreds of exoplanets (with thousands of candidates yet to be confirmed) it stared 3000-light-years deep into a single patch of sky. TESS will scan hundreds of thousands of the brightest and closest stars in our galactic neighborhood.

“TESS will find many planets,” explained Seager in our interview. “The ones we’re highlighting it will find are rocky planets transiting small stars.” One of the missions goals is to find earth-like exoplanets in the habitable zone – the band around a star where water can exist in its liquid state.

The team hopes that TESS will find up to 1000 exoplanets in the first two years of searching. This will give astronomers a wealth of new worlds to study in more detail.

While the stars Kepler examined were faint and difficult to study in follow-up observations, the stars TESS will focus on are bright and close to home. These stars will be prime targets for further scrutiny with other space based telescopes.

“We plan to have a pool of planets, maybe a handful of them, that we can follow up with the James Webb Space Telescope … which will look at the atmospheres of those transiting planets, looking for signs of life,” Seager said.

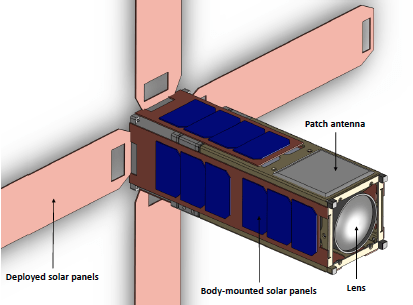

ExoplanetSat

While slightly under the radar, ExoplanetSat will monitor bright stars using nano-satellites. Each nano-satellite will be capable of monitoring a single, bright, sun-like star for two years.

“The way that we describe this mission is not that we will find earth,” Seager said. “But if there is a transiting earth-like planet around a bright sun-like star, we will find it.”

Currently no planned mission has the capability to survey the brightest stars in the sky. TESS will observe stars of magnitude 5 through 12 – the dimmest our eyes can see and fainter.

The brightest stars are too widely spaced for a single telescope to continuously monitor. The best method is to monitor the brightest sun-like stars in a targeted star search instead.

The mission is pretty far along in terms of funding. It has already received a few million dollars and is about one million short of launching the first prototype.

After a successful demonstration the goal is to launch a fleet of nano-satellites to observe enough bright stars to find a number of interesting exoplanets. One day we may be able to look at a bright star in our night sky and know it has a planet.

Direct Imaging Missions

Disentangling a faint, barely reflective, exoplanet from its overwhelmingly bright host star in a direct image seems nearly impossible. A common analogy is looking for a firefly next to a searchlight across North America. Needless to say, very few exoplanets have been seen directly.

Because of the difficulties NASA is fostering a study and soliciting applications with a single goal in mind: create a mission that will directly image exoplanets under a price cap of one billion dollars.

Seager is working with a team that plans to utilize a star shade – “a specially shaped screen that will fly far from the telescope and block out the light from the star so precisely that we will see any planets like earth.”

The shade isn’t circular but shaped like a flower. Light waves would bend around a circle and create spots brighter than the planets themselves. The flower-like shape avoids this while blocking out the starlight – making a planet that is one ten billionth as bright as its host star visible.

The star shade and the telescope have to be aligned perfectly at 125,000 miles away. Once aligned, the system will observe a distant star, and then move to another distant star and re-align. This is technologically speaking, unchartered territory.

While this mission may not occur in full tomorrow, or even years from tomorrow, astronomers’ synapses are firing. We’re coming up with new techniques that will advance technology and find earth-like worlds.

Etc.

Above is a list of only a handful of future exoplanet missions – all at various stages in their production – with some still on the drawing board and others having received full funding and preparing for launch. With creativity and advancing technology we’ll detect a true-earth analogue in the near future.

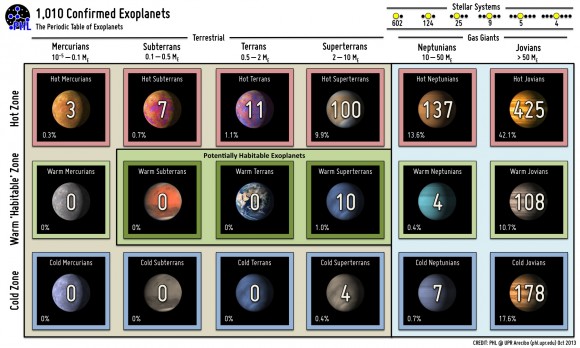

It was just last week that we reported on the oh-so-close approach to 1,000 confirmed exoplanets discovered thus far, and now it’s official: the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia now includes more than 1,000! (1,010, to be exact.)

21 years after the first planets beyond our own Solar System were even confirmed to exist, it’s quite a milestone!

The milestone of 1,000 confirmed exoplanets was surpassed on October 22, 2013 after twenty-one years of discoveries. The long-established and well-known Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia now lists 1,010 confirmed exoplanets.

Not all current exoplanet catalogs list the same numbers as this depends on their particular criteria. For example, the more recent NASA Exoplanet Archive lists just 919. Nevertheless, over 3,500 exoplanet candidates are waiting for confirmation.

The first confirmed exoplanets were discovered by the Arecibo Observatory in 1992. Two small planets were found around the remnants of a supernova explosion known as a pulsar. They were the surviving cores of former planets or newly formed bodies from the ashes of a dead star. This was followed by the discovery of exoplanets around sun-like stars in 1995 and the beginning of a new era of exoplanet hunting.

(The first exoplanets to be confirmed were two orbiting pulsar PSR B1257+12, 1,000 light-years away. A third was found in 2007.)

Exoplanet discoveries have been full of surprises from the outset. Nobody expected exoplanets around the remnants of a dead star (i.e. PSR 1257+12), nor Jupiter-size orbiting close to their stars (i.e. 51 Pegasi). We also know today of stellar systems packed with exoplanets (i.e. Kepler-11), around binary stars (i.e. Kepler-16), and with many potentially habitable exoplanets (i.e. Gliese 667C).

Read more: Earthlike Exoplanets are All Around Us

“The discovery of many worlds around others stars is a great achievement of science and technology. The work of scientists and engineers from many countries were necessary to achieve this difficult milestone. However, one thousand exoplanets in two decades is still a small fraction of those expected from the billions of stars in our galaxy. The next big goal is to better understand their properties, while detecting many new ones.”

– Prof. Abel Mendéz, Associate Professor of Physics and Astrobiology, UPR Arecibo

Source: Press release by Professor Abel Méndez at the Planetary Habitability Laboratory (PHL) at Arecibo

Read more: Kepler Can Still Hunt For Earth-Sized Exoplanets

While not illustrating the full 1,010 lineup, this is still a mesmerizing visualization by Daniel Fabrycky of 885 planetary candidates in 361 systems as found by the Kepler mission. (I for one am looking forward to the third installment!)

Of course, scientists are still hunting for the “Holy Grail” of extrasolar planets: an Earth-sized, rocky world orbiting a Sun-like star within its habitable zone. But with new discoveries and confirmations happening almost every week, it’s now only a matter of time. Read more in this recent article by Universe Today writer David Dickinson.

Kepler may not be hanging up its planet-hunting hat just yet. Even though two of its four reaction wheels — which are crucial to long-duration observations of distant stars — are no longer operating, it could still be able to seek out potentially-habitable exoplanets around smaller stars. In fact, in its new 2-wheel mode, Kepler might actually open up a whole new territory of exoplanet exploration looking for Earth-sized worlds orbiting white dwarfs.

An international team of scientists, led by Mukremin Kilic of the University of Oklahoma’s Department of Physics and Astronomy, are suggesting that NASA’s Kepler spacecraft should turn its gaze toward dim white dwarfs, rather than the brighter main-sequence stars it was previously observing.

“A large fraction of white dwarfs (WDs) may host planets in their habitable zones. These planets may provide our best chance to detect bio-markers on a transiting ex- oplanet, thanks to the diminished contrast ratio between the Earth-sized WD and its Earth-sized planets. The James Webb Space Telescope is capable of obtaining the first spectroscopic measurements of such planets, yet there are no known planets around WDs. Here we propose to take advantage of the unique capability of the Kepler space- craft in the 2-Wheels mode to perform a transit survey that is capable of identifying the first planets in the habitable zone of a WD.”

– Kilic et al.

Any bio-markers — such as molecular oxygen, O2 — could later be identified around such Earth-sized exoplanets by the JWST, they propose.

Because Kepler’s precision has been greatly reduced by the failure of a second reaction wheel earlier this year, it cannot accurately aim at large stars for the long periods of time required to identify the minute dips in brightness caused by the silhouetted specks of passing planets. But since white dwarfs — the dim remains of stars like our Sun — are much smaller, any eclipsing exoplanets would make a much more pronounced effect on their apparent luminosity.

In effect, exoplanets ranging from Earth- to Jupiter-size orbiting white dwarfs as close as .03 AU — well within their habitable zones — would significantly block their light, making Kepler’s diminished aim not so much of an issue.

“Given the eclipse signature of Earth-size and larger planets around WDs, the systematic errors due to the pointing problems is not the limiting factor for WDHZ observations,” the team assures in their paper “Habitable Planets Around White Dwarfs: an Alternate Mission for the Kepler Spacecraft.”

Even smaller orbiting objects could potentially be spotted in this fashion, they add… perhaps even as small as the Moon.

The team is proposing a 200-day-long survey of 10,000 known white dwarfs within the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) area, and expects to find up to 100 exoplanet candidates as well as other “eclipsing short period stellar and sub-stellar companions.”

“If the history of exoplanet science has taught us anything, it is that planets are ubiquitous and they exist in the most unusual places, including very close to their host stars and even around pulsars… Currently there are no known planets around WDs, but we have never looked at a sufficient number of WDs at high cadence to find them through transit observations.”

– Kilic et al.

Read the team’s full report here, and learn more about the Kepler mission here.

NASA’s Ames Research Center made an open call for proposals regarding Kepler’s future operations on August 2. Today is the due date for submissions, which will undergo a review process until Nov. 1, 2013.

Added 9/4: For another take on this, check out Paul Gilster’s write-up on Centauri Dreams.

It’s time for another Weekly Space Hangout, where a dedicated team of space journalists run down all the big stories in space and astronomy for the week of July 26, 2013.

Host: Fraser Cain

Panel: Jason Major, Scott Lewis, David Dickinson

Stories:

Astrological Sign of the Royal Baby

Cosmos Trailer Showcased at Comiccon

Asteroid 2003 DZ15 Close Pass on Monday

Comet ISON Image with Galaxies

Delta Aquarids Meteor Shower

Pale Blue Dot II

Apollo 11 Anniversary

Some Success with the Kepler Recovery

We record the Weekly Space Hangout live as a Google+ Hangout on Air every Friday at Noon Pacific, 3:00 pm Eastern. You can watch the show live on Google+, or here on Universe Today. But you can also watch the archive after the fact, if live video isn’t your thing.