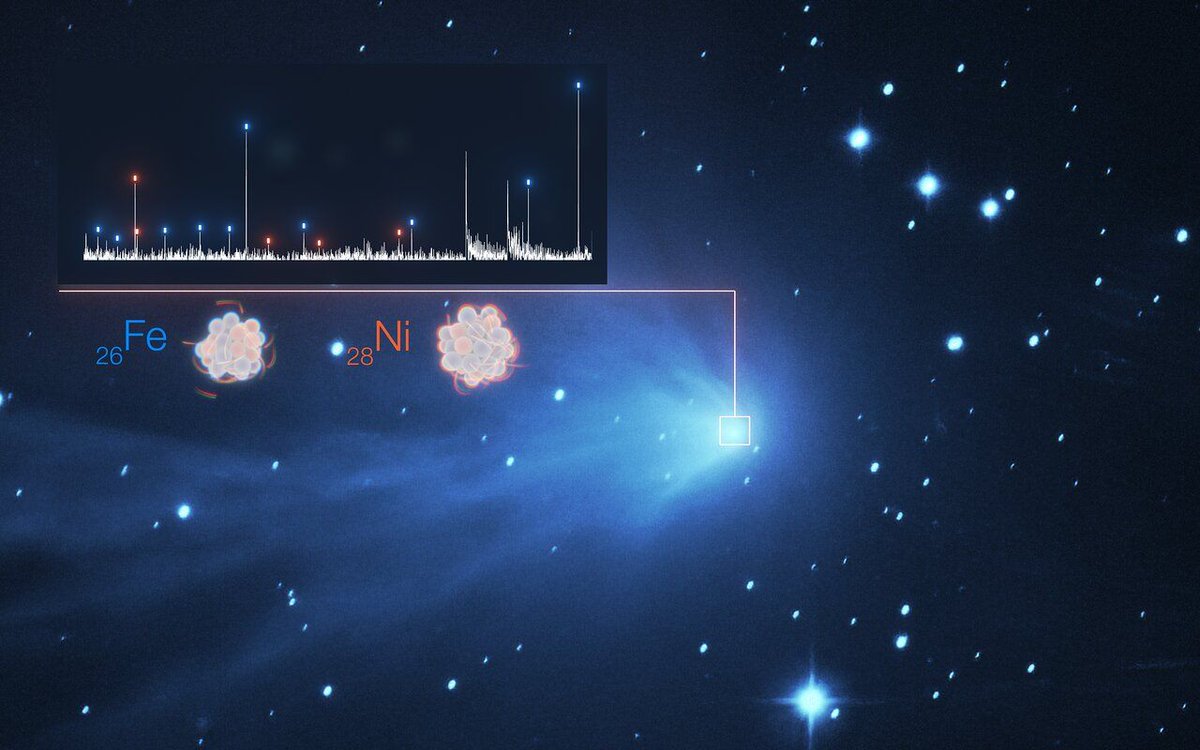

In outer space, an object’s location has a huge impact on its temperature. The closer the object is to its star, the hotter it most likely is. Heat then plays a major role in what materials are present in that object’s atmosphere, if it has one. Lighter elements such as hydrogen and helium and much easier to take a gaseous state and create an atmosphere. So it came as a surprise when two different teams found much heavier elements in the atmosphere of comets that were relatively far away from the Sun. And one of those comets happened to be from another solar system.

Continue reading “Comets Have Tails of gas, Dust… and Metal?”The Solar System has been Flying Through the Debris of a Supernova for 33,000 Years

An Ancient Voyage

Earth is on a journey…

While our planet orbits the Sun each year – a billion kilometers – our entire Solar System is drifting through the Milky Way Galaxy making one rotation every 225-250 million years (that means dinosaurs actually lived on the other side of the Galaxy!) Humanity has been on Earth for a small fraction of that journey, but parts of what we’ve missed is chronicled. It is written into the rock and life of our planet by the explosions of dying stars – supernova. Turns out supernovas write in radioactive ink called Iron-60.

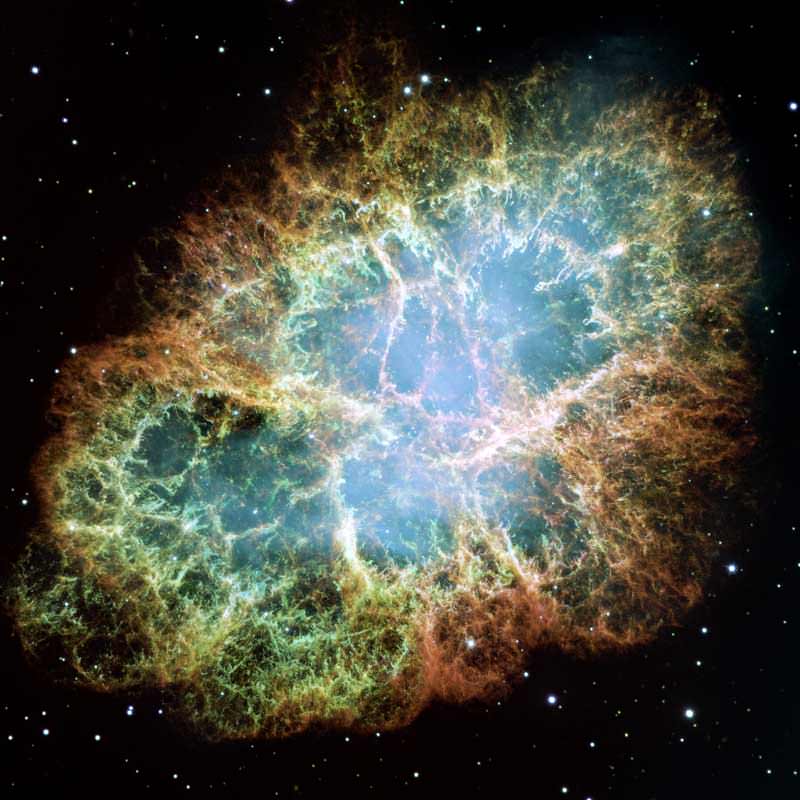

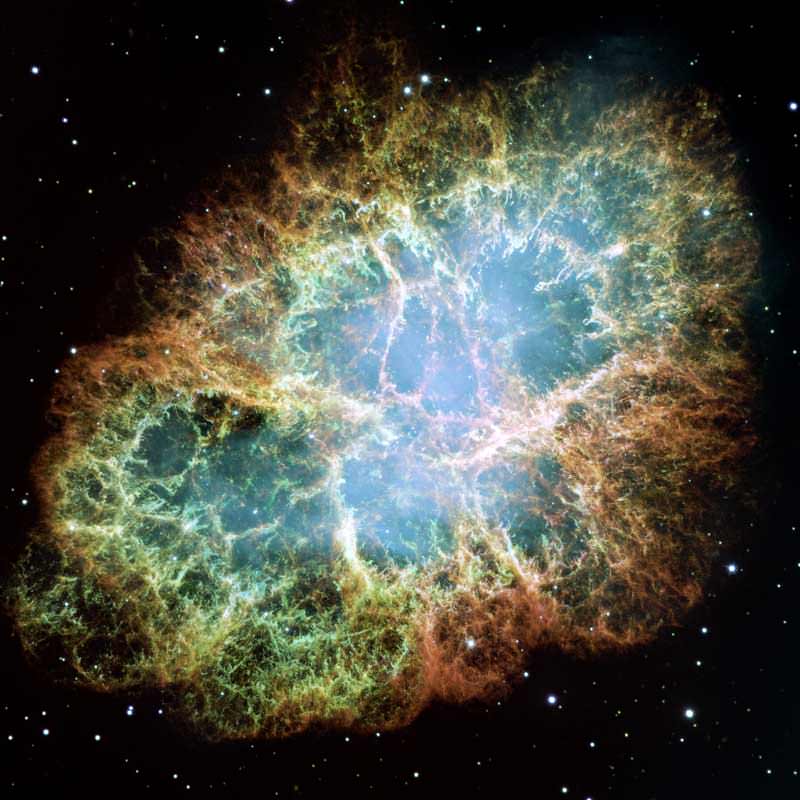

As the Sun travels through the Galaxy, so too do the hundreds of billions of other stars that comprise the Milky Way; all swirling and spiraling in varying directions. If you could time travel to a distant past, you’d look up and see an unfamiliar sky – different stars, different constellations, and sometimes the glow of a brilliant supernova. Stars explode in the Milky Way about once every fifty years. Given the immense size of the Galaxy at around 150,000 light years in diameter, the odds of one of those stars exploding in our backyard is low. But while supernova happen in the Galaxy twice a century, those in close proximity to Earth, within 400 light years, do happen once every few million years. And along Earth’s epic 4.5 billion-year journey, it appears that we’ve had close encounters with supernova several times. In fact, we seem to be travelling through the fallout cloud of supernovae right now.

Continue reading “The Solar System has been Flying Through the Debris of a Supernova for 33,000 Years”A Supernova 2.6 Million Years Ago Could Have Wiped Out the Ocean’s Large Animals

For many years, scientists have been studying how supernovae could affect life on Earth. Supernovae are extremely powerful events, and depending on how close they are to Earth, they could have consequences ranging from the cataclysmic to the inconsequential. But now, the scientists behind a new paper say they have specific evidence linking one or more supernova to an extinction event 2.6 million years ago.

About 2.6 million years ago, one or more supernovae exploded about 50 parsecs, or about 160 light years, away from Earth. At that same time, there was also an extinction event on Earth, called the Pliocene marine megafauna extinction. Up to a third of the large marine species on Earth were wiped out at the time, most of them living in shallow coastal waters.

“This time, it’s different. We have evidence of nearby events at a specific time.” – Dr. Adrian Melott, University of Kansas.

Continue reading “A Supernova 2.6 Million Years Ago Could Have Wiped Out the Ocean’s Large Animals”

A History Of Violence: Iron Found in Fossils Suggests Supernova Role In Mass Dying

Outer space touches us in so many ways. Meteors from ancient asteroid collisions and dust spalled from comets slam into our atmosphere every day, most of it unseen. Cosmic rays ionize the atoms in our upper air, while the solar wind finds crafty ways to invade the planetary magnetosphere and set the sky afire with aurora. We can’t even walk outside on a sunny summer day without concern for the Sun’s ultraviolet light burning out skin.

So perhaps you wouldn’t be surprised that over the course of Earth’s history, our planet has also been affected by one of the most cataclysmic events the universe has to offer: the explosion of a supergiant star in a Type II supernova event. After the collapse of the star’s core, the outgoing shock wave blows the star to pieces, both releasing and creating a host of elements. One of those is iron-60. While most of the iron in the universe is iron-56, a stable atom made up of 26 protons and 30 neutrons, iron-60 has four additional neutrons that make it an unstable radioactive isotope.

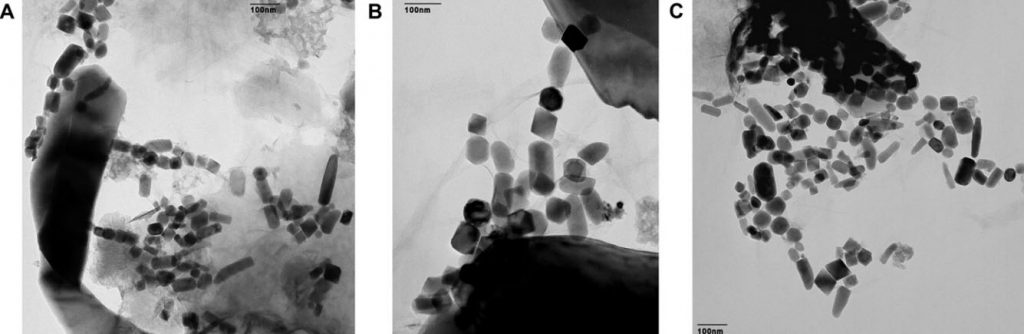

If a supernova occurs sufficiently close to our Solar System, it’s possible for some of the ejecta to make its way all the way to Earth. How might we detect these stellar shards? One way would be to look for traces of unique isotopes that could only have been produced by the explosion. A team of German scientists did just that. In a paper published earlier this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, they report the detection of iron-60 in biologically produced nanocrystals of magnetite in two sediment cores drilled from the Pacific Ocean.

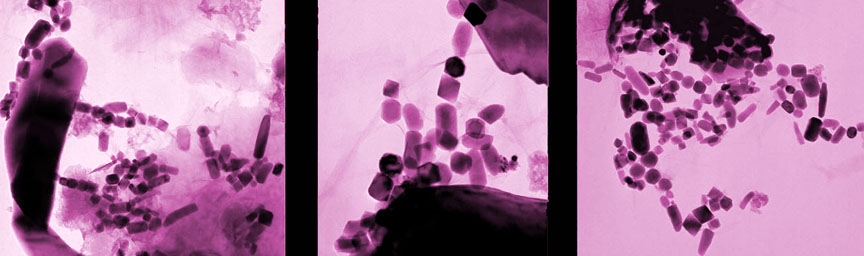

Magnetite is an iron-rich mineral naturally attracted to a magnet just as a compass needle responds to Earth’s magnetic field. Magnetotactic bacteria, a group of bacteria that orient themselves along Earth’s magnetic field lines, contain specialized structures called magnetosomes, where they store tiny magnetic crystals – primarily as magnetite (or greigite, an iron sulfide) in long chains. It’s thought nature went to all this trouble to help the creatures find water with the optimal oxygen concentration for their survival and reproduction. Even after they’re dead, the bacteria continue to align like microscopic compass needles as they settle to the bottom of the ocean.

After the bacteria die, they decay and dissolve away, but the crystals are sturdy enough to be preserved as chains of magnetofossils that resemble beaded garlands on the family Christmas tree. Using a mass spectrometer, which teases one molecule from another with killer accuracy, the team detected “live” iron-60 atoms in the fossilized chains of magnetite crystals produced by the bacteria. Live meaning still fresh. Since the half-life of iron-60 is only 2.6 million years, any primordial iron-60 that seeded the Earth in its formation has long since disappeared. If you go digging around now and find iron-60, you’re likely looking at at a supernova as the smoking gun.

Co-authors Peter Ludwig and Shawn Bishop, along with the team, found that the supernova material arrived at Earth about 2.7 million years ago near the boundary of the Pleistocene and Pliocene epochs and rained down for all of 800,000 years before coming to an end around 1.7 million years ago. If ever a hard rain fell.

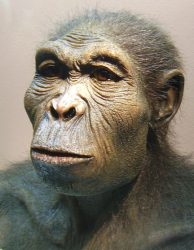

The peak concentration occurred about 2.2 million years ago, the same time our early human ancestors, Homo habilis, were chipping tools from stone. Did they witness the appearance of a spectacularly bright “new star” in the night sky? Assuming the supernova wasn’t obscured by cosmic dust, the sight must have brought our bipedal relations to their knees.

There’s even a possibility that an increase in cosmic rays from the event affected our atmosphere and climate and possibly led to a minor die-off at the time. Africa’s climate dried out and repeated cycles of glaciation became common as global temperatures continued their cooling trend from the Pliocene into the Pleistocene.

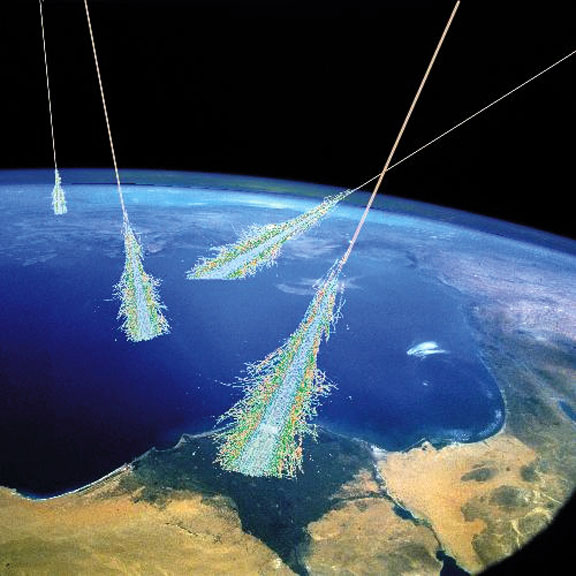

Cosmic rays, which are extremely fast-moving, high-energy protons and atomic nucleic, rip up molecules in the atmosphere and can even penetrate down to the surface during a nearby supernova explosion, within about 50 light years of the Sun. The high dose of radiation would put life at risk, while at the same time providing a surge in the number of mutations, one of the creative forces driving the diversity of life over the history of our planet. Life — always a story of taking the good with the bad.

The discovery of iron-60 further cements our connection to the universe at large. Indeed, bacteria munching on supernova ash adds a literal twist to the late Carl Sagan’s famous words: “The cosmos is within us. We are made of star-stuff.” Big or small, we owe our lives to the synthesis of elements within the bellies of stars.

Cosmic Explosion Left Imprint in Fossil Record

Ancient iron-loving bacteria may have scooped up evidence of a nearby supernova explosion 2.2 million years ago, leaving an extraterrestrial iron signature in the fossil record, according to German researchers presenting their findings at a recent meeting of the American Physical Society.

In 2004, German scientists reported finding an isotope of iron in a core sample from the Pacific Ocean that does not form on Earth. The scientists calculated the decay rate of the radioactive isotope iron-60 and determined that the source was from a nearby supernova about 2 million years ago. The blast, they say, was close enough to Earth to seriously damage the ozone layer and may have contributed to a marine extinction at the Pliocene-Pleistocene geologic boundary.

Shawn Bishop, a physicist with the Technical University of Munich in Germany and the primary author of the recent study, wondered if traces of the supernova could be found in the fossil record as well. Some deep sea bacteria soak up iron creating tiny magnetic crystals. These 100-nanometer-wide crystals form long chains inside highly-specialized organelles called magnetosomes which help the bacteria orient themselves to Earth’s magnetic field. Using a core sample from the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean, Bishop and his team sampled strata spaced about 100,000 years apart. By using a chemical treatment that extracts iron-60 while leaving other iron, the scientists then ran the sample through a mass spectrometer to determine whether iron-60 was present.

And in the layers around 2.2 million years ago, tiny traces of iron-60 appeared.

Although the scientists are not sure which star exploded to rain radioactive iron onto Earth, the scientists refer to a paper from 2002 that points to several supernovae generated in the Scorpius-Centaurus star association. The group of young stars, just 130 parsecs (about 424 light-years) from Earth, has produced 20 supernovae within the past 11 million years.

Source: Nature.com and APS.org “Abstract X8.00002: Search for Supernova 60FE in the Earth’s Fossil Record”, Physical Review Letters, “Evidence for Nearby Supernova Explosions” and 60Fe Anomaly in a Deep-Sea Manganese Crust and Implications for a Nearby Supernova Source.