Testing is one of the unsung steps in the engineering process. Talk to any product development engineer, and they will tell you how big of a milestone passing “V&V” – or verification and validation – testing is. Testing is even more critical when you work on equipment meant for the harsh space environment. It is also more challenging to mimic those harsh environments on Earth. Luckily for some of NASA’s more critical upcoming missions, another government agency has a unique test lab to help V&V with some of its most critical components – their heat shields.

Continue reading “Testing Heat Shields for Different Atmospheres”An Innovative Heat Shield That Doesn’t Need to Be Replaced Between Missions

A revolution in space manufacturing is coming. Enabled by cheaper launch costs, companies are scrambling to take advantage of easier access to the benefits space offers as a manufacturing environment. These include a constant vacuum, near absolute zero temperatures, and a lack of any significant gravity. These features would enable easier processing and manufacturing of hundreds of products, from pharmaceuticals to metal alloys. The tricky part is getting them back down to Earth, where they can be used.

A company based in the UK recently revealed what they think is a viable solution for that. Space Forge, which is developing a reusable manufacturing platform for use in space, recently discussed their Pridwen heat shield. The most remarkable thing about this new heat shield is it’s reusable.

Continue reading “An Innovative Heat Shield That Doesn’t Need to Be Replaced Between Missions”SpaceX Releases a New Render of What the All-Steel Starship Will Look Like Returning to Earth

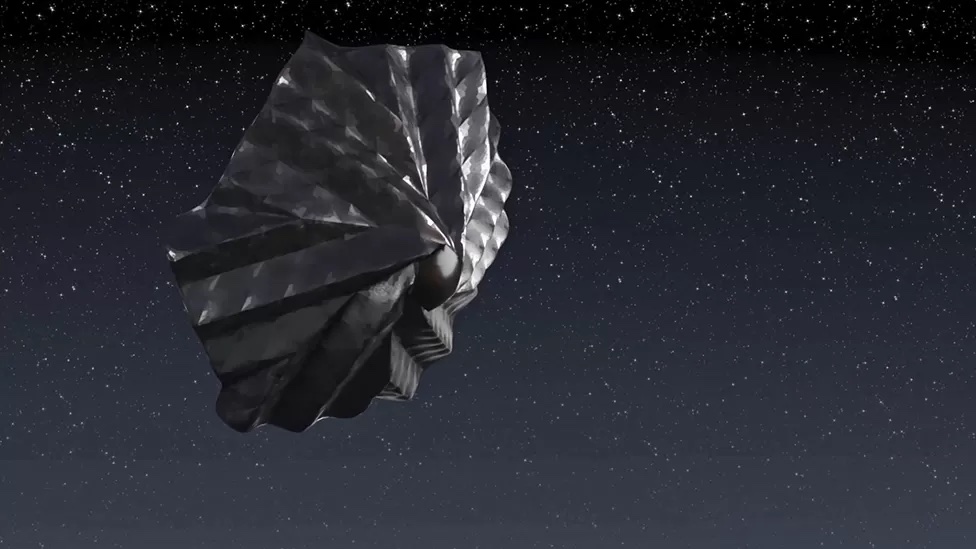

The design for SpaceX’s Starship (aka. Big Falcon Rocket) is really starting to come together! Over the holidays, sections of the Starship Hopper (a miniature version of the Starship) were photographed being put together at the company’s South Texas Launch Site. By mid-January, the parts were fully-integrated, forming the body of the stainless-steel prototype that would test the spacecraft’s overall architecture.

What followed, earlier this month, were tests of the Starship’s hexagonal heat shields to determine if they would offer sufficient protection during re-entry. And now, in anticipation of the spacecraft’s eventual launch, SpaceX released an eye-popping new rendering of the Starship that shows what it would look like reentering Earth’s atmosphere.

Continue reading “SpaceX Releases a New Render of What the All-Steel Starship Will Look Like Returning to Earth”Spinning Heat Shield Concept Could Provide a Lightweight Way to Survive Atmospheric Re-entry

One of the more challenging aspects of space exploration and spacecraft design is planning for re-entry. Even in the case of thinly-atmosphered planets like Mars, entering a planet’s atmosphere is known to cause a great deal of heat and friction. For this reason, spacecraft have always been equipped with heat shields to absorb this energy and ensure that the spacecraft do not crash or burn up during re-entry.

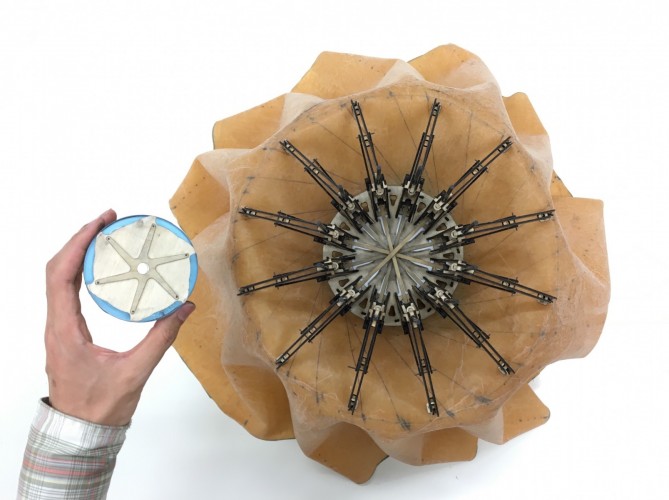

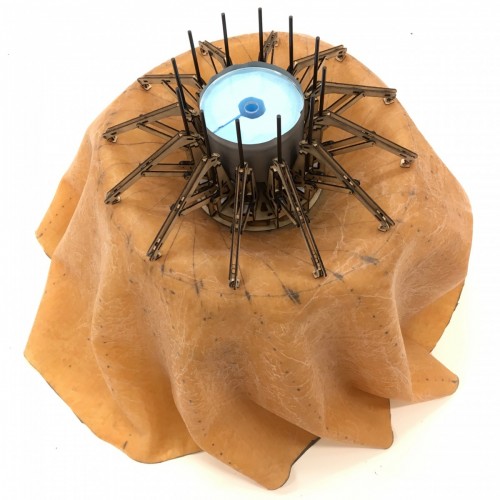

Unfortunately, current spacecraft must rely on huge inflatable or mechanically deployed shields, which are often heavy and complicated to use. To address this, a PhD student from the University of Manchester has developed a prototype for a heat shield that would rely on centrifugal forces to stiffen flexible, lightweight materials. This prototype, which is the first of its kind, could reduce the cost of space travel and facilitate future missions to Mars.

The concept was proposed by Rui Wu, a PhD student from Manchester’s School of Mechanical, Aerospace and Civil Engineering (MACE). He was joined by Peter C.E. Roberts and Carl Driver – a Senior Lecturer in Spacecraft Engineering and a Lecturer at MACE, respectively – and Constantinos Soutis of The University of Manchester Aerospace Research Institute.

To put it simply, planets with atmospheres allow spacecraft to utilize aerodynamic drag to slow down in preparation for landing. This process creates a tremendous amount of heat. In the case of Earth’s atmosphere, temperatures of 10,000 °C (18,000 °F) are generated and the air around the spacecraft can turn into plasma. For this reason, spacecraft require a front-end mounted heat shield that can tolerate extreme heat and is aerodynamic in shape.

When deploying to Mars, the circumstances are somewhat different, but the challenge remains the same. While the Martian atmosphere is less than 1% that of Earth’s – with an average surface pressure of 0.636 kPa compared to Earth’s 101.325 kPa – spacecraft still require heat shields to avoid burnup and carry heavy loads. Wu’s design potentially solves both of these issues.

The prototype’s design, which consists of a skirt-shaped shield designed to spin, seeks to create a heat shield that can accommodate the needs of current and future space missions. As Wu explained:

“Spacecraft for future missions must be larger and heavier than ever before, meaning that heat shields will become increasingly too large to manage… Spacecraft for future missions must be larger and heavier than ever before, meaning that heat shields will become increasingly too large to manage.”

Wu and his colleagues described their concept in a recent study that appeared in the journal Arca Astronautica (titled “Flexible heat shields deployed by centrifugal force“). The design consists of an advanced, flexible material that has a high temperature tolerance and allows for easy-folding and storage aboard a spacecraft. The material becomes rigid as the shield applies centrifugal force, which is accomplished by rotating upon entry.

So far, Wu and his team have conducted a drop test with the prototype from an altitude of 100 m (328 ft) using a balloon (the video of which is posted below). They also conducted a structural dynamic analysis that confirmed that the heat shield is capable of automatically engaging in a sufficient spin rate (6 revolutions per second) when deployed from altitudes of higher than 30 km (18.64 mi) – which coincides with the Earth’s stratosphere.

The team also conducted a thermal analysis that indicated that the heat shield could reduce front end temperatures by 100 K (100 °C; 212 °F) on a CubeSat-sized vehicle without the need for thermal insulation around the shield itself (unlike inflatable structures). The design is also self-regulating, meaning that it does not rely on additional machinery, reducing the weight of a spacecraft even further.

And unlike conventional designs, their prototype is scalable for use aboard smaller spacecraft like CubeSats. By being equipped with such a shield, CubeSats could be recovered after they re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere, effectively becoming reusable. This is all in keeping with current efforts to make space exploration and research cost-effective, in part through the development of reusable and retrievable parts. As Wu explained:

“More and more research is being conducted in space, but this is usually very expensive and the equipment has to share a ride with other vehicles. Since this prototype is lightweight and flexible enough for use on smaller satellites, research could be made easier and cheaper. The heat shield would also help save cost in recovery missions, as its high induced drag reduces the amount of fuel burned upon re-entry.”

When it comes time for heavier spacecraft to be deployed to Mars, which will likely involve crewed missions, it is entirely possible that the heat shields that ensure they make it safely to the surface are composed of lightweight, flexible materials that spin to become rigid. In the meantime, this design could enable lightweight and compact entry systems for smaller spacecraft, making CubeSat research that much more affordable.

Such is the nature of modern space exploration, which is all about cutting costs and making space more accessible. And be sure to check out this video from the team’s drop test as well, courtesy of Rui Wui and the MACE team:

Further Reading: University of Manchester, Acta Astronica

World’s Largest Heat Shield Attached to NASA’s Orion Crew Capsule for Crucial Fall 2014 Test Flight

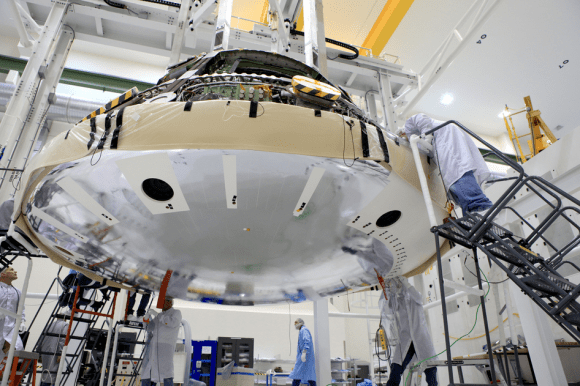

Lockheed Martin and NASA engineers are installing the largest heat shield ever built onto the Orion EFT-1 spacecraft’s crew module at the Kennedy Space Center. Liftoff is slated for late Fall 2014. Credit: Lockheed Martin

Story updated[/caption]

In a key milestone, technicians at the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida have attached the world’s largest heat shield to a pathfinding version of NASA’s Orion crew capsule edging ever closer to its inaugural unmanned test flight later this Fall on a crucial mission dubbed Exploration Flight Test-1 (EFT-1).

One of the primary goals of NASA’s eagerly anticipated Orion EFT-1 uncrewed test flight is to test the efficacy of the heat shield in protecting the vehicle – and future human astronauts – from excruciating temperatures reaching 4000 degrees Fahrenheit (2200 C) during scorching re-entry heating.

A trio of parachutes will then unfurl to slow Orion down for a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

Orion is NASA’s next generation human rated vehicle now under development to replace the now retired space shuttle. The state-of-the-art spacecraft will carry America’s astronauts on voyages venturing farther into deep space than ever before – past the Moon to Asteroids, Mars and Beyond!

“The Orion heat shield is the largest of its kind ever built. Its wider than the Apollo and Mars Science Lab heat shields,” Todd Sullivan told Universe Today. Sullivan is the heat shield senior manager at Lockheed Martin, Orion’s prime contractor.

The heat shield measures 16.5 feet (5 m) in diameter.

Lockheed Martin and NASA technicians mated the heat shield to the bottom of the capsule during assembly work inside the Operations and Checkout High Bay facility at KSC.

“Holes were drilled into the heat shield from the inside to the outside at the structural attached points at the underside of the crew module,” said Jules Schneider, Orion Project manager for Lockheed Martin at KSC, during a recent exclusive interview by Universe Today inside the Orion clean room at KSC.

“Then its opened up from the outside and bolted in place underneath. Closeout plugs made of Avcoat are then installed to close it up and seal the gaps,” Schneider explained.

The heat shield is constructed from a single seamless piece of Avcoat ablator, that was applied by engineers at Textron Defense System near Boston, Mass.

“They applied the Avcoat ablater material to the outside. That’s what protects the spacecraft from the heat of reentry,” Sullivan explained.

The ablative material will wear away as it heats up during the capsules atmospheric re-entry thereby preventing the 4000 degree F heat from being transferred to the rest of the capsule and saving it and the human crew from utter destruction.

Orion EFT-1 is slated to launch in December 2014 atop the mammoth, triple barreled United Launch Alliance (ULA) Delta IV Heavy rocket, currently the most powerful booster in America’s fleet.

The Delta IV Heavy is the only rocket with sufficient thrust to launch the Orion EFT-1 capsule and its attached upper stage to its intended orbit of 3600 miles altitude above Earth – about 15 times higher than the International Space Station (ISS) and farther than any human spacecraft has journeyed in 40 years.

At the conclusion of the two-orbit, four- hour EFT-1 flight, the detached Orion capsule plunges back and re-enters the Earth’s atmosphere at 20,000 MPH (32,000 kilometers per hour).

“That’s about 80% of the reentry speed experienced by the Apollo capsule after returning from the Apollo moon landing missions,” Scott Wilson, NASA’s Orion Manager of Production Operations at KSC, told me during an interview at KSC.

“The big reason to get to those high speeds during EFT-1 is to be able to test out the thermal protection system, and the heat shield is the biggest part of that.”

“Numerous sensors and instrumentation have been specially installed on the EFT-1 heat shield and the back shell tiles to collect measurements of things like temperatures, pressures and stresses during the extreme conditions of atmospheric reentry,” Wilson explained.

The heat shield arrived at KSC in December 2013 loaded inside NASA’s Super Guppy aircraft while I was onsite. Read my story – here.

The data gathered during the unmanned EFT-1 flight will aid in confirming. or refuting, design decisions and computer models as the program moves forward to the first flight atop NASA’s mammoth SLS booster in late 2017 on the EM-1 mission and more human crewed missions thereafter.

Recently, the EFT-1 launch was postponed three months from its long planned slot in mid-September to December 2014 when NASA was ordered to make way for the accelerated launch of recently declassified US Air Force Space Surveillance satellites that were given a higher priority.

The covert Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program, or GSSAP, satellites were only unveiled in Feb. 2014 during a speech by General William Shelton, commander of the US Air Force Space Command.

Despite the EFT-1 launch postponement, Kennedy Space Center Director Bob Cabana said technicians are pressing forward and continue to work around the clock at KSC in order to still be ready in time to launch by the original launch window that opens in mid- September 2014.

“The contractor teams are working to get the Orion spacecraft done on time for the December 2017 launch,” said Cabana.

“They are working seven days a week in the Operations and Checkout High Bay facility to get the vehicle ready to roll out for the EFT-1 mission and be mounted on top of the Delta IV Heavy.”

“I can assure you the Orion will be ready to go on time, as soon as we get our opportunity to launch that vehicle on its first flight test and that is pretty darn amazing.”

“Our plan is to have the Orion spacecraft ready because we want to get EFT-1 out so we can start getting the hardware in for Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1) and start processing for that vehicle that will launch on the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket in 2017,” Cabana told me

Concurrently, new American-made private crewed spaceships are under development by SpaceX, Boeing and Sierra Nevada – with funding from NASA’s Commercial Crew Program (CCP) – to restore US capability to ferry US astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS) and back to Earth by late 2017.

Read my exclusive new interview with NASA Administrator Charles Bolden explaining the importance of getting Commercial Crew online – here.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Orion, Boeing, SpaceX, Orbital Sciences, commercial space, Curiosity, Mars rover, MAVEN, MOM and more planetary and human spaceflight news.

Ken Kremer Delta 4 Heavy rocket and super secret US spy satellite roar off Pad 37 on June 29, 2012 from Cape Canaveral, Florida. NASA’s Orion EFT-1 capsule will blastoff atop a similar Delta 4 Heavy Booster in December 2014. Credit: Ken Kremer- kenkremer.com[/caption]

Delta 4 Heavy rocket and super secret US spy satellite roar off Pad 37 on June 29, 2012 from Cape Canaveral, Florida. NASA’s Orion EFT-1 capsule will blastoff atop a similar Delta 4 Heavy Booster in December 2014. Credit: Ken Kremer- kenkremer.com[/caption]