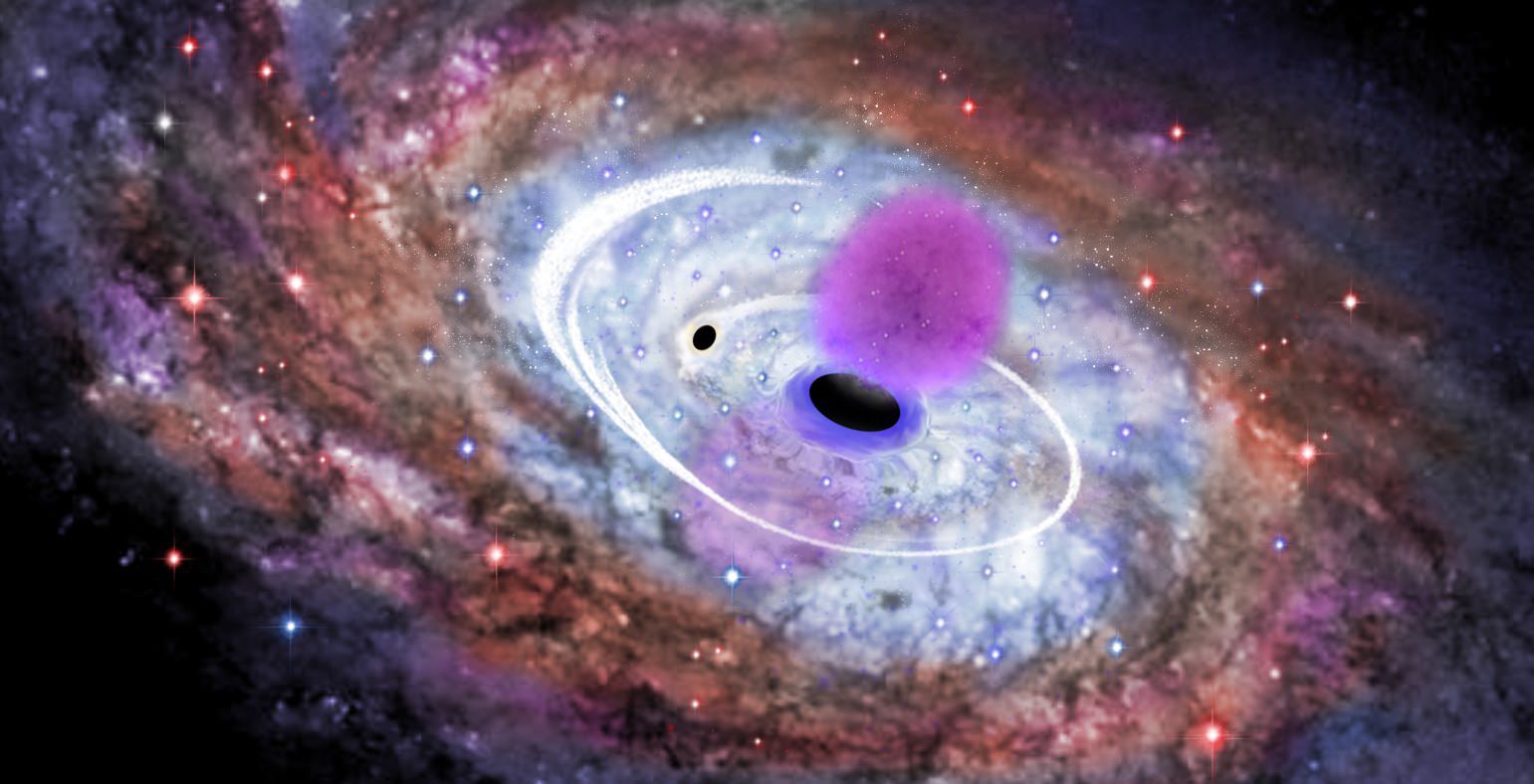

Deep at the heart of our galaxy lurks a black hole. This isn’t exciting news, but neither is it a very exciting place. Or is it? While all might be quiet on the western front now, there may be evidence that our galactic center was once home to some pretty impressive activity – activity which may have included multiple collision events and mergers of black holes as it gorged on a satellite galaxies. Thanks to new insights from a pair of assistant professors, Kelly Holley-Bockelmann at Vanderbilt and Tamara Bogdanovic at Georgia Institute of Technology, we have more evidence which points to the Milky Way’s incredibly active past.

“Tamara and I had just attended an astronomy conference in Aspen, Colorado, where several of these new observations were announced,” said Holley-Bockelmann. “It was January 2010 and a snow storm had closed the airport. We decided to rent a car to drive to Denver. As we drove through the storm, we pieced together the clues from the conference and realized that a single catastrophic event – the collision between two black holes about 10 million years ago – could explain all the new evidence.”

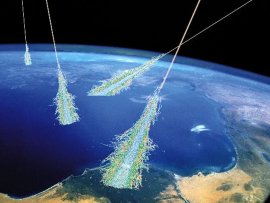

Now, imagine a night sky illuminated by a a huge nebula, one that covers half the celestial sphere. This isn’t a dream, it’s a reality. These massive lobes of high-energy radiation are known as Fermi bubbles and they cover a region some 30,000 light years on either side of the Milky Way’s core. While we can’t observe them directly in visible light, these particles are moving along at close to 186,000 miles per second and glowing in x-ray and gamma ray wavelengths.

According to Fulai Guo and William G. Mathews of the University of California at Santa Cruz: “The Fermi bubbles provide plausible evidence for a recent powerful AGN jet activity in our Galaxy, shedding new insights into the origin of the halo CR population and the channel through which massive black holes in disk galaxies release feedback energy during their growth.”

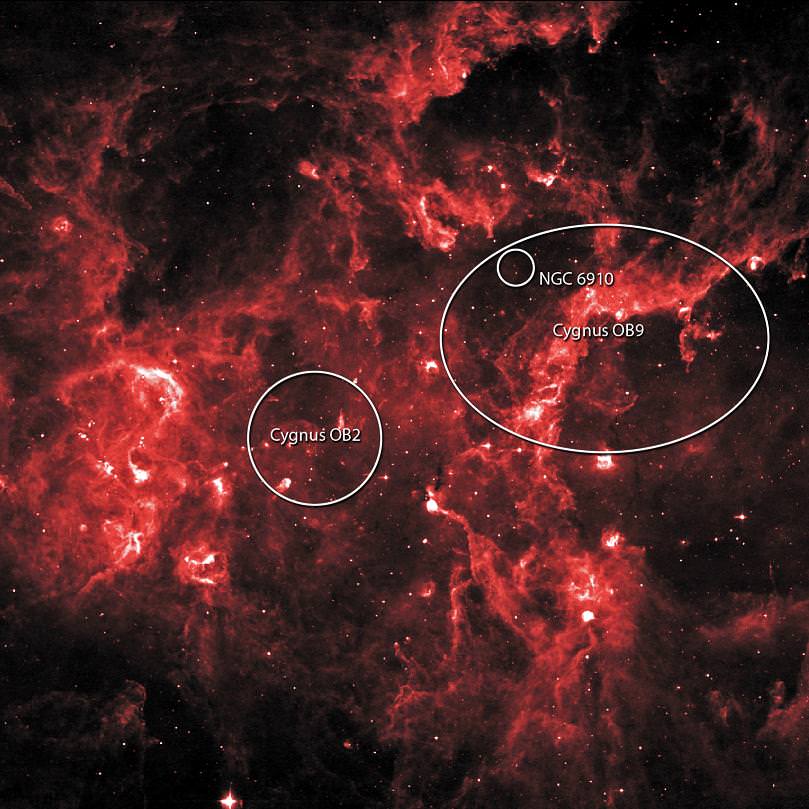

However, our galactic center is home to more than just some incredible bubbles – it’s the location of three of the most massive clusters of young stars within the Milky Way’s realm. Known as the Central, Arches and Quintuplet clusters, each grouping houses several hundred hot, young stars which dwarf the Sun. They will live short, bright, violent lives… burning out in a scant few million years. Because they live fast and die young, these cluster stars must have formed within recent years during a eruption of star formation near the galactic center – another clue to this cosmic puzzle.

“Because of their high mass, and apparent top-heavy IMF, the Galactic Center clusters contain some of the most massive stars in the Galaxy. This is important, as massive stars are key ingredients and probes of astrophysical phenomena on all size and distance scales, from individual star formation sites, such as Orion, to the early Universe during the age of reionization when the first stars were born. As ingredients, they control the dynamical and chemical evolution of their local environs and individual galaxies through their influence on the energetics and composition of the interstellar medium.” says Donald F. Figer. “They likely play an important role in the early evolution of the first galaxies, and there is evidence that they are the progenitors of the most energetic explosions in the Universe, seen as gamma ray bursts. As probes, they define the upper limits of the star formation process and their presence likely ends further formation of nearby lower mass stars. They are also prominent output products of galactic mergers, starburst galaxies, and active galactic nuclei.”

To deepen the mystery, take a closer look at our central black hole. It spans about 40 light seconds in diameter and weighs about four million solar masses. According to what we know, this should produce intensive gravitational tides – ones that should be sucking in the surroundings. So how is it that astronomers have uncovered groups of new, bright stars closer than 3 light years from the event horizon? Of course, they could be on their way to oblivion, but the data shows these stars seem to have formed there. That’s quite a feat considering it would require a molecular cloud 10,000 times more dense than the one located at our galactic center! Shouldn’t there also be old stars located there as well? The answer is yes, there should be… but there are far fewer than what we can observe and what current theoretical models predict.

Holley-Bockelmann wasn’t about to let the problem rest. When she returned home, she enlisted the aid of Vanderbilt graduate student Meagan Lang to help solve the riddle. Then they recruited Pau Amaro-Seoane from the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics in Germany, Alberto Sesana from the Institut de Ciències de l’Espai in Spain, and Vanderbilt Research Assistant Professor Manodeep Sinha to help. With so many bright minds to help solve this riddle, they soon arrived at a plausible explanation – one which matches observations and allows for testable predictions.

According to their theory, a Milky Way satellite galaxy began migrating towards our core. As it merged with our galaxy, its mass was torn away, leaving only its black hole and a small collection of gravitationally bound stars. After several million years, this “leftover” eventually reached the galactic center and the black holes began to merge. As the smaller black hole was swirled around the larger, it plowed up huge furrows of gas and dust, pushing it into the larger black hole and created the Fermi bubbles. The dueling gravitational forces weren’t gentle… these intense tides were quite capable of compressing the molecular clouds surrounding the core into the density required to produce fresh, young stars. Perhaps the very young stars we now observe at the galactic center?

However, there’s more to the picture than meets the eye. This same plowing of the cosmic turf would have also pushed out existing older stars from the vicinity of the massive central black hole. It’s a scene which fits current models where a black hole merger flings stars out into the galaxy at hyper velocities… a scene which fits the observation of a lack of old stars at the boundaries of our supermassive black hole.

“The gravitational pull of the satellite galaxy’s black hole could have carved nearly 1,000 stars out of the galactic centre,” said Bogdanovic. “Those stars should still be racing through space, about 10,000 light years away from their original orbits.”

Can any of this be proved? The answer is yes. Thanks to large scale surveys like the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, we should be able to pinpoint stars moving at a higher velocity than stars which haven’t been subjected to a similar interaction. If astronomers like Holley-Bockelmann and Bogdanovic look at the hard evidence, they are likely to discover a credible number of high velocity stars which will validate their Milky Way merger model.

Or are they just blowing bubbles?

![A composite illustration of the AGILE satellite and the Crab Nebula imaged by the Chandra observatory. [Image courtesy of ASI, INAF and NASA]](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/tavani1HR.jpg)