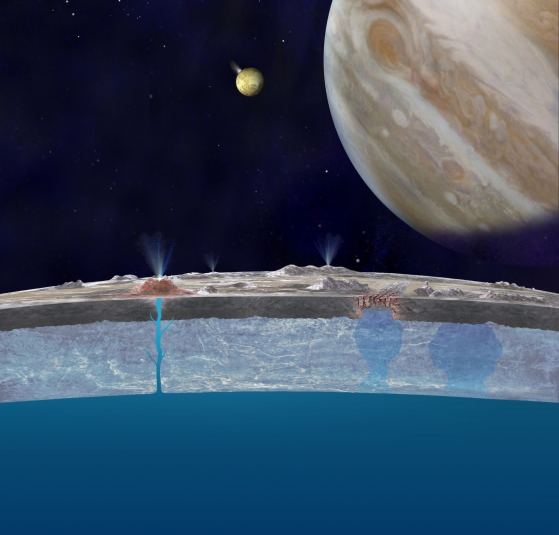

Astronomer Mike Brown and his colleague Kevin Hand might be suffering from “Pump Handle Phobia,” as radio personality Garrison Keillor calls it, where those afflicted just can’t resist putting their tongues on something frozen to see if it will stick. But Brown and Hand are doing it all in the name of science, and they may have found the best evidence yet that Europa has a liquid water ocean beneath its icy surface. Better yet, that vast subsurface ocean may actually shoot up to Europa’s surface, on occasion.

In a recent blog post, Brown pondered what it would taste like if he could lick the icy surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa. “The answer may be that it would taste a lot like that last mouthful of water that you accidentally drank when you were swimming at the beach on your last vacation. Just don’t take too long of a taste. At nearly 300 degrees (F) below zero your tongue will stick fast.”

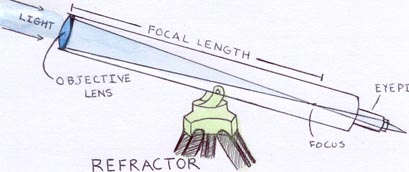

His ponderings were based on a new paper by Brown and Hand which combined data from the Galileo mission (1989 to 2003) to study Jupiter and its moons, along with new spectroscopy data from the 10-meter Keck II telescope in Hawaii.

The study suggests there is a chemical exchange between the ocean and surface, making the ocean a richer chemical environment.

“We now have evidence that Europa’s ocean is not isolated—that the ocean and the surface talk to each other and exchange chemicals,” said Brown, who is an astronomer and professor of planetary astronomy at Caltech. “That means that energy might be going into the ocean, which is important in terms of the possibilities for life there. It also means that if you’d like to know what’s in the ocean, you can just go to the surface and scrape some off.”

“The surface ice is providing us a window into that potentially habitable ocean below,” said Hand, deputy chief scientist for solar system exploration at JPL.

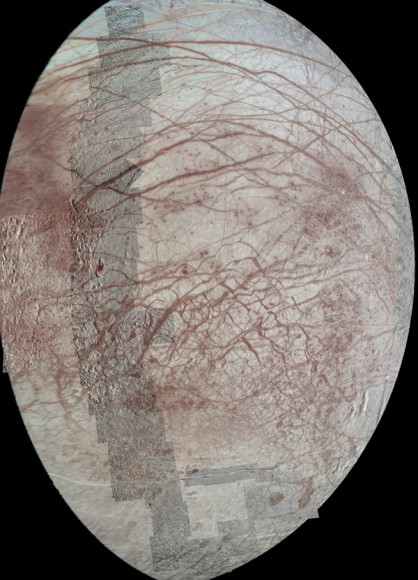

Europa’s ocean is thought to cover the moon’s whole globe and is about 100 kilometers (60 miles) thick under a thin ice shell. Since the days of NASA’s Voyager and Galileo missions, scientists have debated the composition of Europa’s surface.

Salts were detected in the Galileo data – “Not ‘salt’ as in the sodium chloride of your table salt,” Brown wrote in his blog, “Mike Brown’s Planets,” “but more generically ‘salts’ as in ‘things that dissolve in water and stick around when the water evaporates.’”

That idea was enticing, Brown said, because if the surface is covered by things that dissolve in water, that strongly implies that Europa’s ocean water has flowed on the surface, evaporated, and left behind salts.

But there were other explanations for the Galileo data, as Europa is constantly bombarded by sulfur from the volcanoes on Io, and the spectrograph that was on the Galileo spacecraft wasn’t able to tell the difference between salts and sulfuric acid.

But now, with data from the Keck Observatory, Brown and Hand have identified a spectroscopic feature on Europa’s surface that indicates the presence of a magnesium sulfate salt, a mineral called epsomite, that could have formed by oxidation of a mineral likely originating from the ocean below.

Brown and Hand started by mapping the distribution of pure water ice versus anything else. The spectra showed that even Europa’s leading hemisphere contains significant amounts of non-water ice. Then, at low latitudes on the trailing hemisphere — the area with the greatest concentration of the non-water ice material — they found a tiny, never-before-detected dip in the spectrum.

The two researchers tested everything from sodium chloride to Drano in Hand’s lab at JPL, where he tries to simulate the environments found on various icy worlds. At the end of the day, the signature of magnesium sulfate persisted.

The magnesium sulfate appears to be generated by the irradiation of sulfur ejected from the Jovian moon Io and, the authors deduce, magnesium chloride salt originating from Europa’s ocean. Chlorides such as sodium and potassium chlorides, which are expected to be on the Europa surface, are in general not detectable because they have no clear infrared spectral features. But magnesium sulfate is detectable. The authors believe the composition of Europa’s ocean may closely resemble the salty ocean of Earth.

While no one is going to be traveling to Europa to lick its surface, for now, astronomers will continue to use the modern giant telescopes on Earth to continue to “take spectral fingerprints of increasing detail to finally understand the mysterious details of the salty ocean beneath the ice shell of Europa,” Brown said.

Also, NASA is looking into options to explore Europa further. (Universe Today likes the idea of a big drill or submarine!)

But in the meantime what happens next? “We look for chlorine, I think,” Brown wrote. “The existence of chlorine as one of the main components of the non-water-ice surface of Europa is the strongest prediction that this hypothesis makes. We have some ideas on how we might look; we’re working on them now. Stay tuned.”

Sources: Mike Brown’s Planets, Keck Observatory, JPL