Astronomers have a thing for big explosions and collisions, and it always seems like they are trying to one-up themselves in finding a bigger, brighter one. There’s a new entrant to that category – an event so big it created a burst of particles over 1 billion years ago that is still visible today and is 60 times bigger than the entire Milky Way.

Continue reading “Astronomers see an Enormous Shockwave, 60 Times Bigger Than the Milky Way”The Large Magellanic Cloud Stole one of its Globular Clusters

Astronomers have known for years that galaxies are cannibalistic. Massive galaxies like our own Milky Way have gained mass by absorbing smaller neighbours.

Now it looks like smaller galaxies like the Large Magellanic Cloud have also feasted on smaller neighbours.

Continue reading “The Large Magellanic Cloud Stole one of its Globular Clusters”Rare Triple Galaxy Merger With at Least Two Supermassive Black Holes

One of the best things about that universe is that there is so much to it. If you look hard enough, you can most likely find any combination of astronomical events happening. Not long ago we reported on research that found 7 separate instances of three galaxies colliding with one another. Now, a team led by Jonathan Williams of the University of Maryland has found another triple galaxy merging cluster, but this one might potentially have two active supermassive black holes, allowing astronomers to peer into the system dynamics of two of the universe’s most extreme objects running into one another.

Continue reading “Rare Triple Galaxy Merger With at Least Two Supermassive Black Holes”Astronomers see a Rare “Double Quasar” in a Pair of Merging Galaxies

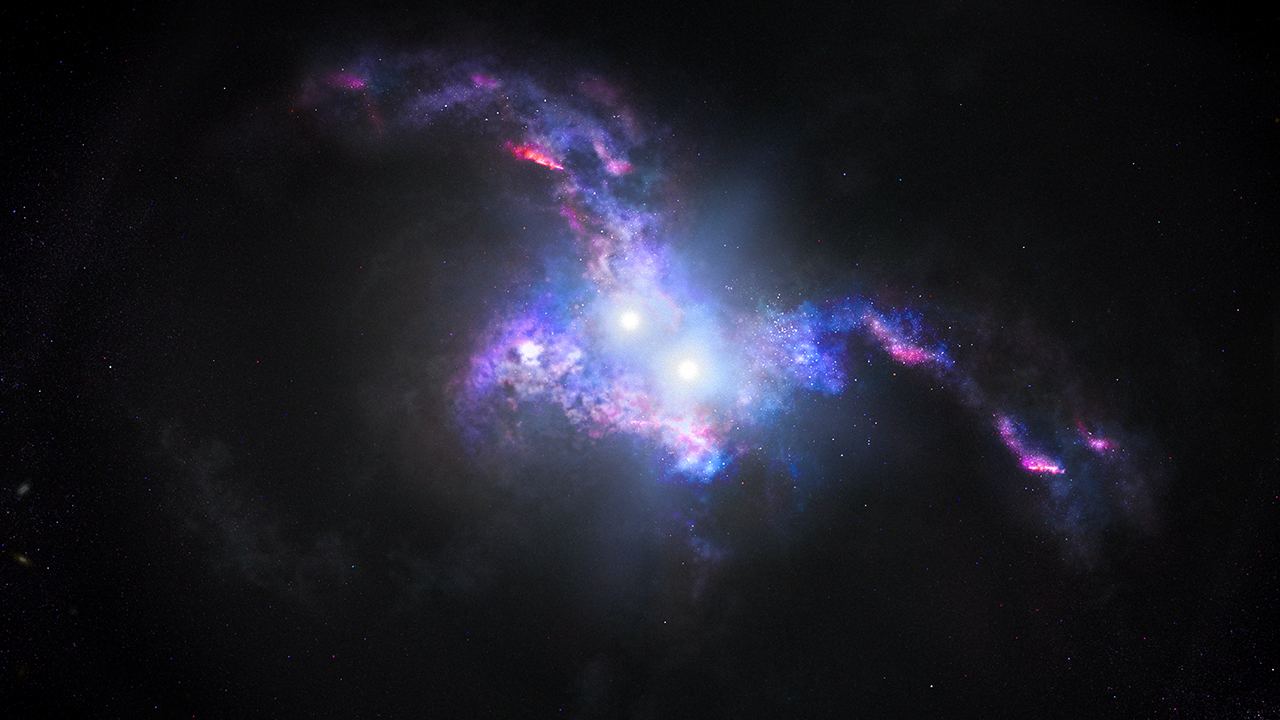

What’s better than a quasar? That’s right, two quasars. Astronomers have spotted for the first time two rare double-quasars, and the results show us the dynamic, messy consequences of galaxy formation.

Continue reading “Astronomers see a Rare “Double Quasar” in a Pair of Merging Galaxies”When Galaxies Collide, Black Holes Don’t Always Get the Feast They Were Hoping for

What happens when galaxies collide? Well, if any humans are around in about a billion years, they might find out. That’s when our Milky Way galaxy is scheduled to collide with our neighbour the Andromeda galaxy. That event will be an epic, titanic, collision. The supermassive black holes at the center of both galaxies will feast on new material and flare brightly as the collision brings more gas and dust within reach of their overwhelming gravitational pull. Where massive giant stars collide with each other, lighting up the skies and spraying deadly radiation everywhere. Right?

Maybe not. In fact, there might be no feasting at all, and hardly anything titanic about it.

Continue reading “When Galaxies Collide, Black Holes Don’t Always Get the Feast They Were Hoping for”Galaxy Mergers can Boost Star Formation, and it can Also Shut it Down

Galaxy mergers are beautiful sights, but ultimately deadly. In the midst of the collision, the combined galaxy will shine brighter than it ever has before. But that glory comes with a price: all those new stars use up all the available fuel, and star formation grinds to a halt.

Continue reading “Galaxy Mergers can Boost Star Formation, and it can Also Shut it Down”Astronomers Find the Hollowed-Out Shell of a Dwarf Galaxy that Collided With the Milky Way Billions of Years Ago

In 2005 astronomers found a dense grouping of stars in the Virgo constellation. It looked like a star cluster, except further surveys showed that some of the stars are moving towards us, and some are moving away. That finding was unexpected and suggested the Stream was no simple star cluster.

A 2019 study showed that the grouping of stars is no star cluster at all; instead, it’s the hollowed-out shell of a dwarf spheroidal galaxy that merged with the Milky Way. It’s called the Virgo Overdensity (VOD) or the Virgo Stellar Stream.

A new study involving some of the same researchers shows how and when the merger occurred and identifies other shells from the same merger.

Continue reading “Astronomers Find the Hollowed-Out Shell of a Dwarf Galaxy that Collided With the Milky Way Billions of Years Ago”A Stellar Stream of Stars, Stolen from Another Galaxy

Modern professional astronomers aren’t much like astronomers of old. They don’t spend every suitable evening with their eyes glued to a telescope’s eyepiece. You might be more likely to find them in front of a super-computer, working with AI and deep learning methods.

One group of researchers employed those methods to find a whole new collection of stars in the Milky Way; a group of stars which weren’t born here.

Continue reading “A Stellar Stream of Stars, Stolen from Another Galaxy”Astronomers Find a Galaxy Containing Three Supermassive Black Holes at the Center

NGC 6240 is a puzzle to astronomers. For a long time, astronomers thought the galaxy is a result of a merger between two galaxies, and that merger is evident in the galaxy’s form: It has an unsettled appearance, with two nuclei and extensions and loops.

Continue reading “Astronomers Find a Galaxy Containing Three Supermassive Black Holes at the Center”Astronomers Have Found a Place With Three Supermassive Black Holes Orbiting Around Each Other

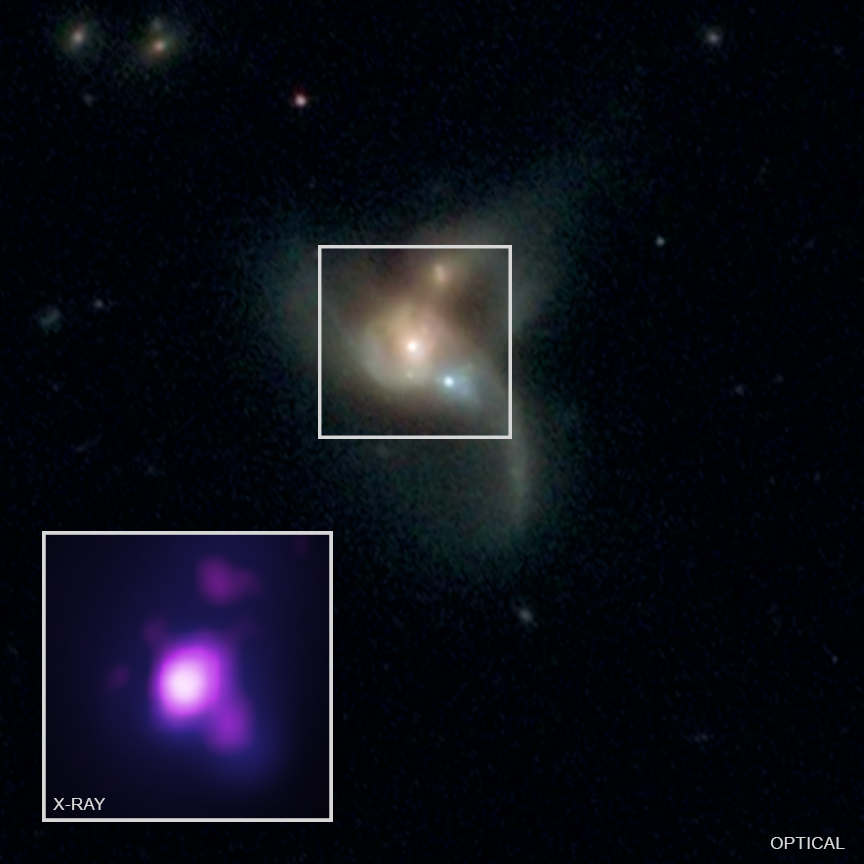

Astronomers have spotted three supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at the center of three colliding galaxies a billion light years away from Earth. That alone is unusual, but the three black holes are also glowing in x-ray emissions. This is evidence that all three are also active galactic nuclei (AGN,) gobbling up material and flaring brightly.

This discovery may shed some light on the “final parsec problem,” a long-standing issue in astrophysics and black hole mergers.

Continue reading “Astronomers Have Found a Place With Three Supermassive Black Holes Orbiting Around Each Other”