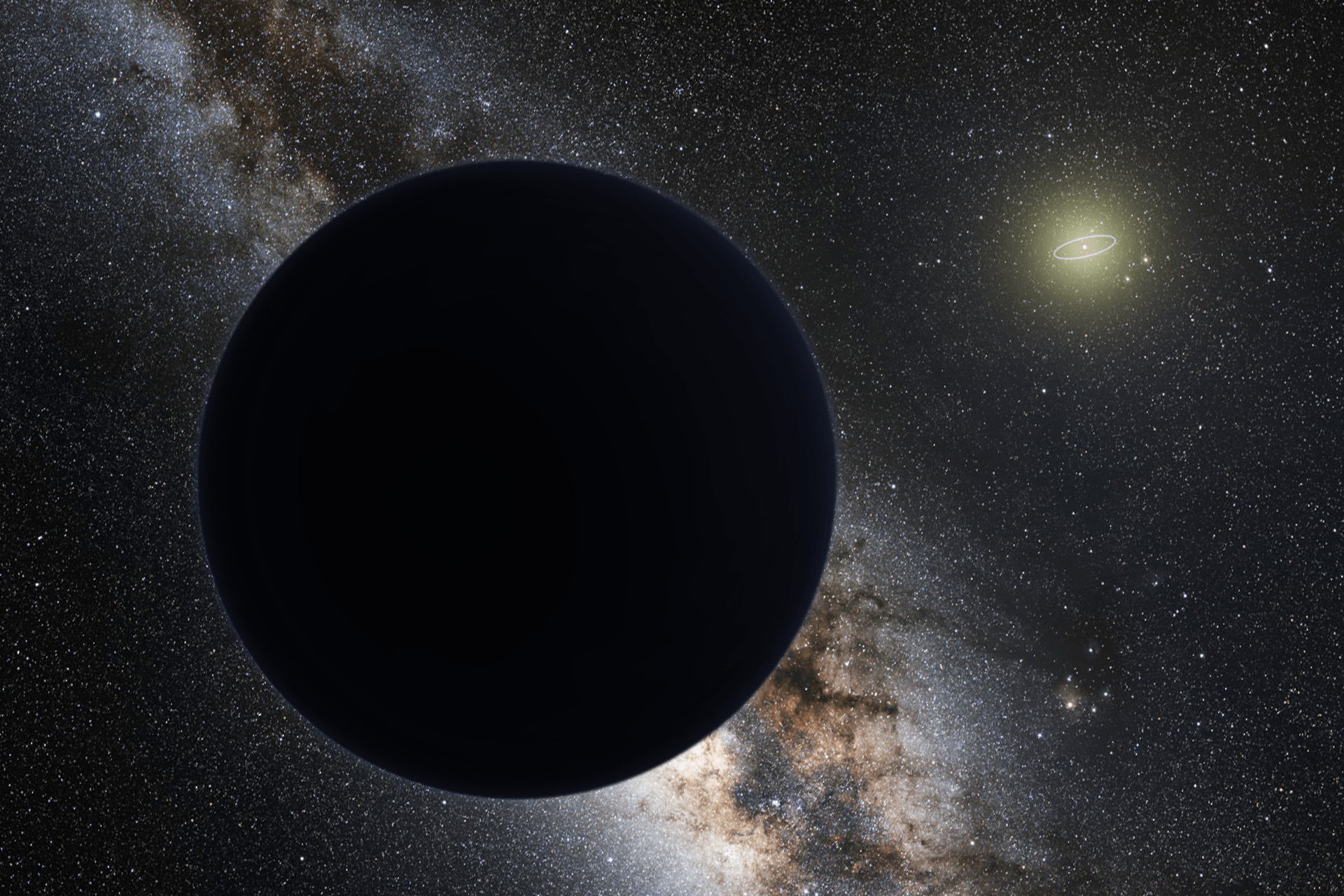

Like all living creatures, stars have a natural lifespan. After going through their main sequence phase, they eventually exhaust their nuclear fuel and begin the slow process towards death. In our Sun’s case, this will consist of it growing in size and entering the Red Giant phase of its evolution. When that happens, roughly 5.4 billion years from now, the Sun will encompass the orbit’s of Mercury, Venus, and maybe even Earth.

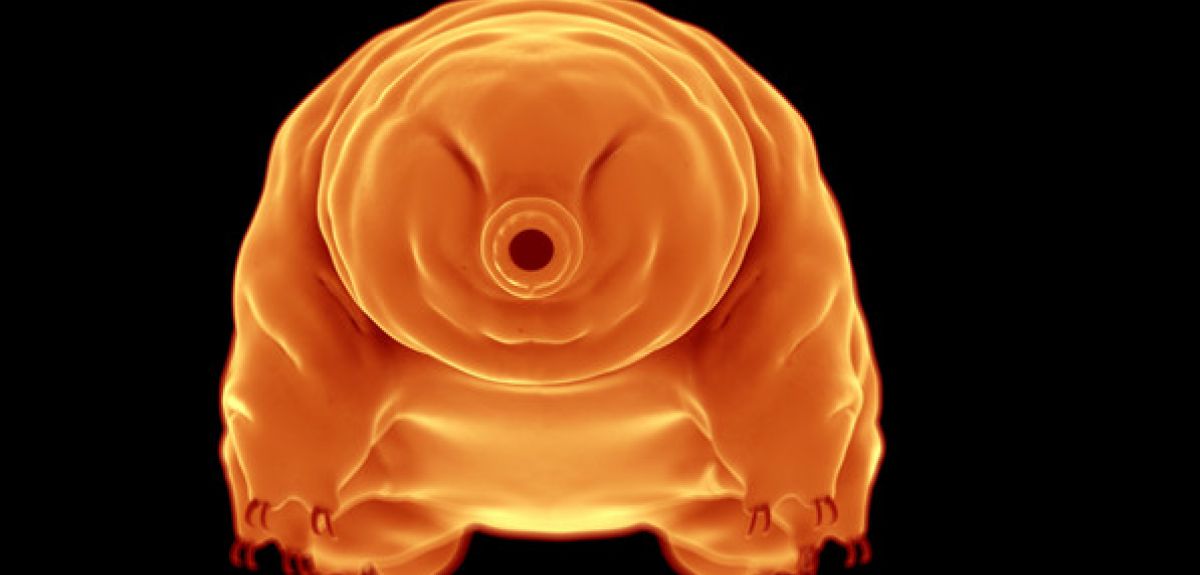

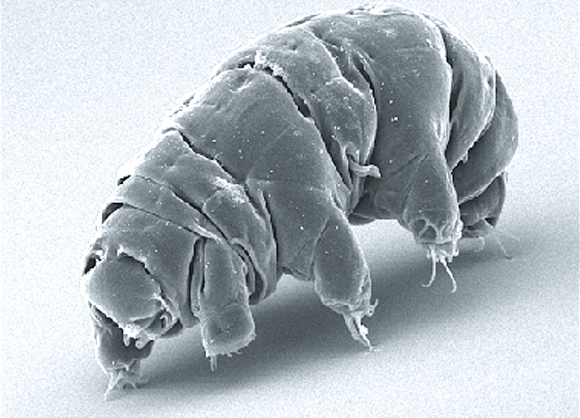

However, even before this happens, astronomers theorize that the Sun will dramatically heat up, which will render Earth uninhabitable to most species. But according to a new study by a team of researchers from Oxford and the University of Harvard, the species known as tardigrades (aka. the “water bear”) will likely survive even after humanity and all other species have perished.

This study, which was recently published in the journal Scientific Reports under the title “The Resilience of Life to Astrophysical Events“, was conducted by Dr. David Sloan, Dr. Rafael Alves Batista – from the Department of Astrophysics at Oxford University – and Dr. Abraham Loeb of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA). As they indicate, previous studies into the effect Solar evolution will have on life have been rather lopsided.

Essentially, much attention has been dedicated to whether or not humanity will survive our Sun leaving its main sequence phase. Comparatively, very little research has been conducted on whether or not life itself (and which lifeforms) will be able to survive this change. As such, they considered the most statistically-likely events that would be capable of completely sterilizing an Earth-like planet, and sought to determine what lifeforms could endure them.

As Dr. Loeb told Universe Today via email, their team wanted to consider if there was an extinction-level event that could eliminate all life on Earth (not just humans):

“We wanted to find out how long life may survive on a planet once formed. Most previous studies focused on the survival of humans which are very sensitive to changes in the atmosphere or climate of the Earth and can be eliminated by the impact of an asteroid (nuclear winter) or bad politics.”

What they found was that the species Milnesium tardigradum would survive all potential astrophysical catastrophes. What’s more, they estimated that these creatures will be around for another 10 billion years at least – far longer than what is anticipated for the human race! As Loeb indicates, this was not an outcome that they were expecting.

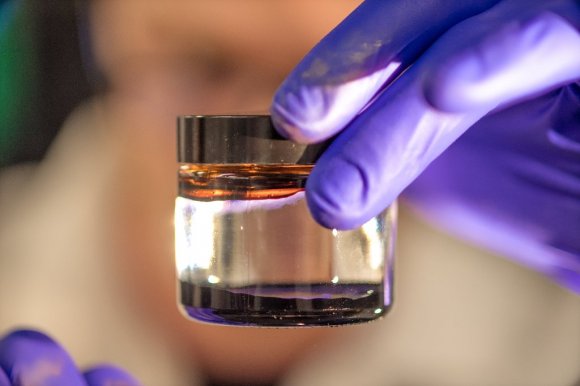

“To our surprise, tardigrades are likely to survive all astrophysical catastrophes,” he said. “Most likely, the DNA of tardigrades is able to repair itself quickly due to damage encountered by the environment. The process is not fully understood, and there is a group at Harvard University who studies the SNA of tardigrades with the hope of understanding it better.”

To be fair, it has been known for some time that Tardigrades are the most resilient life form on Earth. Not only can they survive for up to 30 years without food or water (half their natural lifespan), they can also survive temperatures of up to 150 °C (302 °F) and as low as -200 °C (-328 °F). They have also shown themselves to be capable of enduring extremes in pressure, ranging from the 6000 atmospheres to the vacuum of open space.

Under these conditions, the research team concluded that they are likely to survive the Sun becoming a red giant and irradiating Earth, and will likely be alive even after the Sun has winked out of existence. On top of that, tardigrades can even be brought back to life, under the right circumstances. Much like all life on Earth, tradigrades need water to survive, even though they can survive in a dry state for extended periods of time – up to ten years, in fact.

But even after being deprived of water to the point of death, scientists have found that these organisms can be reanimated once water is reintroduced. This was demonstrated in 2007 when a batch of tardigrades was dehydrated before being launched to Low Earth Orbit (LEO). After being exposed to the hard vacuum of space and UV radiation for 10 days, they were returned to Earth and rehydrated – at which point, the majority were revived and able to produce viable embryos.

The team also concluded that other cataclysmic events – such as an asteroid strike, exploding stars (i.e. a supernovae) or gamma ray bursts – pose no existential threat to tardigrades. As Loeb explained:

“We have found that asteroid impacts are capable of boiling off all the oceans on Earth, but only if the asteroid is more massive than 1018 kg [10,000 trillion metric tons]. Such events are extremely rare and will not happen before the Sun will die; the probability of them happening earlier is less than one part in a million.”

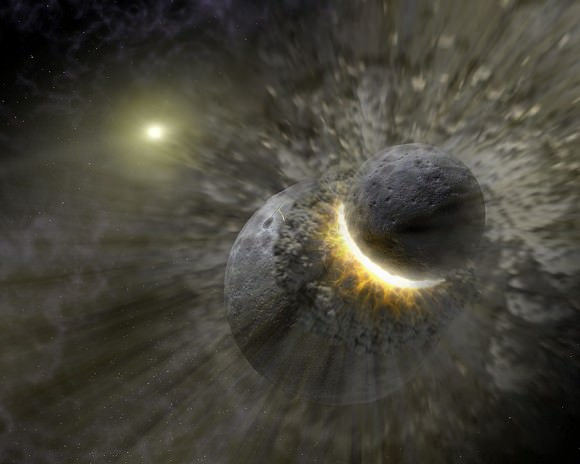

In fact, the last time an object large enough to boil the oceans (2 x 1018 kg) collided with Earth occurred roughly 4.51 billion years ago. On this occasion, Earth was struck by a Mars-sized object named Theia, which is believed to be what caused the formation of the Moon. Today, there are only a dozen known asteroids or dwarf planets in the Solar System that have this kind of mass, and none of them will intersect the Earth’s orbit in the future.

As for supernova, they indicated that an exploding star would need to be 0.14 light-years from Earth in order for it to boil the oceans from its surface. Since the closest star to our Sun (Proxima Centauri) is 4.25 light years away, this scenario is not a foreseeable risk. As for gamma-ray bursts, which are even rarer than supernova, the team determined that they too are too far away from Earth to pose a threat.

The implications of this study are quite fascinating. For one, it reminds us just how fragile human life is compared to basic, microscopic life forms. It also demonstrates that similarly hardy organisms could exist in a variety of locations that we may have once considered too hostile for life. As Dr Rafael Alves Batista, one of the co-authors on the study, said in a University of Oxford press release:

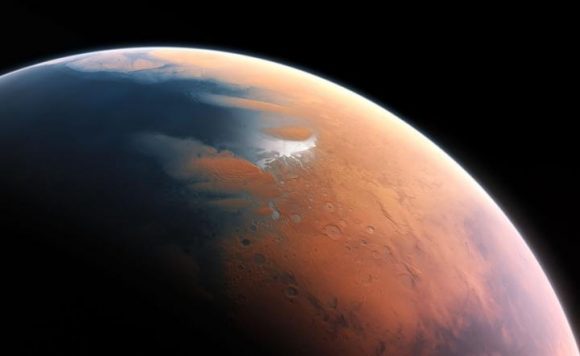

“Without our technology protecting us, humans are a very sensitive species. Subtle changes in our environment impact us dramatically. There are many more resilient species’ on earth. Life on this planet can continue long after humans are gone. Tardigrades are as close to indestructible as it gets on Earth, but it is possible that there are other resilient species examples elsewhere in the Universe. In this context there is a real case for looking for life on Mars and in other areas of the Solar System in general. If Tardigrades are earth’s most resilient species, who knows what else is out there?’”

And as Dr. Loeb explained, studies like this have potential benefits that go far beyond assessing our own survivability. Not only do they help us understand life’s ability to endure catastrophic events – which is essential to understanding how and where life could emerge in the Universe – but they also offer possibilities on how we might better our own chances of survival.

“We get a better understanding of the conditions under which life will persist,” he said. “In about a billion years, when the Sun will heat up life will cease, but until then it will continue in some form. Understanding the self-repair mechanism of the DNA on tardigrades could potentially help in combating disease for humans as well.”

And all his time, we thought cockroaches were the toughest critters on the planet, what with their ability to withstand a nuclear holocaust. But these eight-legged creatures, which are arguably cuter than cockroaches too, clearly have the market on toughness cornered. We’re just lucky they only get up to 0.5 mm (0.02 in) in size, otherwise we might have something to worry about!

Further Reading: University of Oxford, Scientific Reports