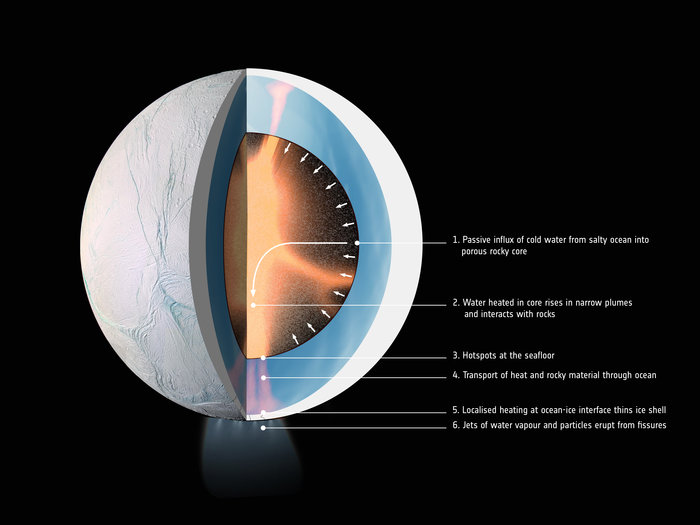

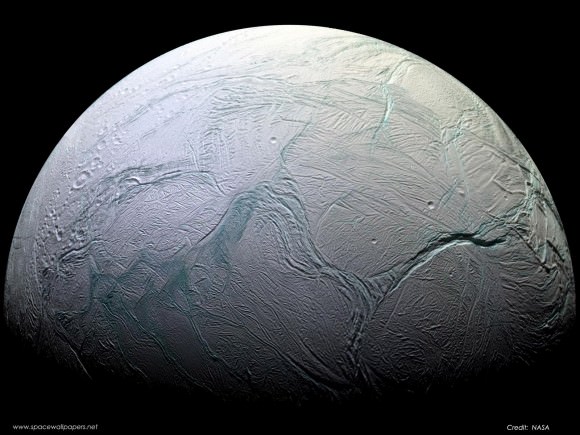

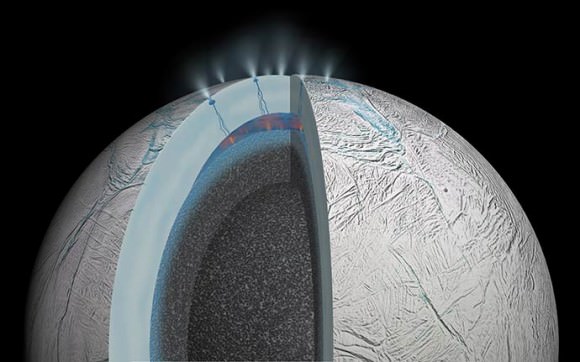

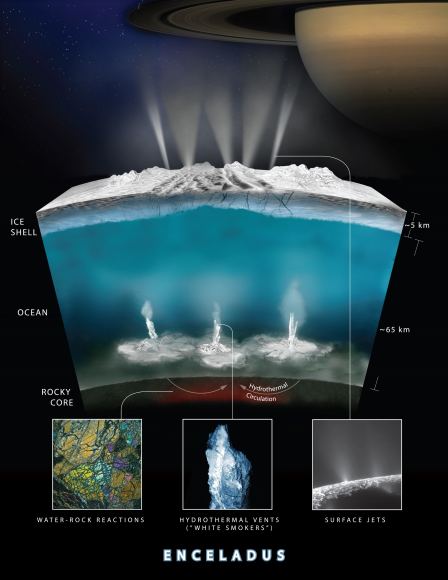

When the Cassini mission arrived in the Saturn system in 2004, it discovered something rather unexpected in Enceladus’ southern hemisphere. From hundreds of fissures located in the polar region, plumes of water and organic molecules were spotted periodically spewing forth. This was the first indication that Saturn’s moon may have an interior ocean caused by hydrothermal activity near the core-mantle boundary.

According to a new study based on Cassini data, which it obtained before diving into Saturn’s atmosphere on September 15th, this activity may have been going on for some time. In fact, the study team concluded that if the moon’s core is porous enough, it could have generated enough heat to maintain an interior ocean for billions of years. This study is the most encouraging indication yet that the interior of Enceladus could support life.

The study, titled “Powering prolonged hydrothermal activity inside Enceladus“, recently appeared in the journal Nature Astronomy. The study was led by Gaël Choblet, a researcher with the Planetary and Geodynamic Laboratory at the University of Nantes, and included members from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Charles University, and the Institute of Earth Sciences and the Geo- and Cosmochemistry Laboratory at the University of Heidelberg.

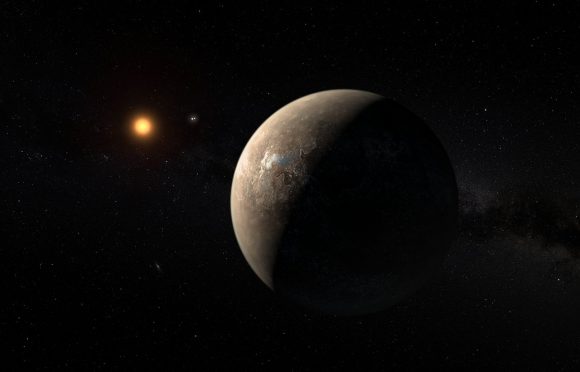

Prior to the Cassini mission’s many flybys of Enceladus, scientists believed this moon’s surface was composed of solid ice. It was only after noticing the plume activity that they came to realize that it had water jets that extended all the way down to a warm-water ocean in its interior. From the data obtained by Cassini, scientists were even able to make educated guesses of where this internal ocean lay.

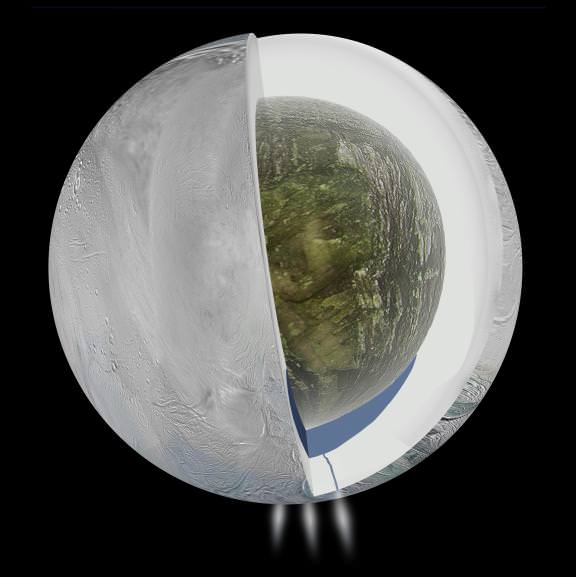

All told, Enceladus is a relatively small moon, measuring some 500 km (311 mi) in diameter. Based on gravity measurements performed by Cassini, its interior ocean is believed to lie beneath an icy outer surface at depths of 20 to 25 km (12.4 to 15.5 mi). However, this surface ice thins to about 1 to 5 km (0.6 to 3.1 mi) over the southern polar region, where the jets of water and icy particles jet through fissures.

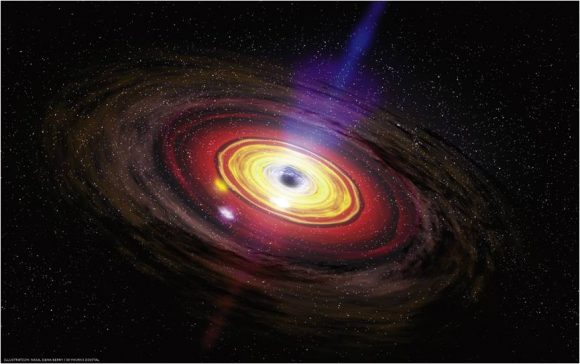

Based on the way Enceladus orbits Saturn with a certain wobble (aka. libration), scientists have been able to make estimates of the ocean’s depth, which they place at 26 to 31 km (16 to 19 mi). All of this surrounds a core which is believed to be composed of silicate minerals and metal, but which is also porous. Despite all these findings, the source of the interior heat has remained something of an open question.

This mechanism would have to be active when the moon formed billions of years ago and is still active today (as evidenced by the current plume activity). As Dr. Choblet explained in an ESA press statement:

“Where Enceladus gets the sustained power to remain active has always been a bit of mystery, but we’ve now considered in greater detail how the structure and composition of the moon’s rocky core could play a key role in generating the necessary energy.”

For years, scientists have speculated that tidal forces caused by Saturn’s gravitational influence are responsible for Enceladus’ internal heating. The way Saturn pushes and pulls the moon as it follows an elliptical path around the planet is also believed to be what causes Enceladus’ icy shell to deform, causing the fissures around the southern polar region. These same mechanisms are believed to be what is responsible for Europa’s interior warm-water ocean.

However, the energy produced by tidal friction in the ice is too weak to counterbalance the heat loss seen from the ocean. At the rate Enceladus’ ocean is losing energy to space, the entire moon would freeze solid within 30 million years. Similarly, the natural decay of radioactive elements within the core (which has been suggested for other moons as well) is also about 100 times too weak to explain Enceladus interior and plume activity.

To address this, Dr. Choblet and his team conducted simulations of Enceladus’ core to determine what kind of conditions could allow for tidal heating over billions of years. As they state in their study:

“In absence of direct constraints on the mechanical properties of Enceladus’ core, we consider a wide range of parameters to characterize the rate of tidal friction and the efficiency of water transport by porous flow. The unconsolidated core of Enceladus can be viewed as a highly granular/fragmented material, in which tidal deformation is likely to be associated with intergranular friction during fragment rearrangements.”

What they found was that in order for the Cassini observations to be borne out, Enceladus’ core would need to be made of unconsolidated, easily deformable, porous rock. This core could be easily permeated by liquid water, which would seep into the core and gradually heated through tidal friction between sliding rock fragments. Once this water was sufficiently heated, it would rise upwards because of temperature differences with its surroundings.

This process ultimately transfers heat to the interior ocean in narrow plumes which rise to the meet Enceladus’ icy shell. Once there, it causes the surface ice to melt and forming fissures through which jets reach into space, spewing water, ice particles and hydrated minerals that replenish Saturn’s E-Ring. All of this is consistent with the observations made by Cassini, and is sustainable from a geophysical point of view.

In other words, this study is able to show that action in Enceladus’ core could produce the necessary heating to maintain a global ocean and produce plume activity. Since this action is a result of the core’s structure and tidal interaction with Saturn, it is perfectly logical that it has been taking place for billions of years. So beyond providing the first coherent explanation for Enceladus’ plume activity, this study is also a strong indication of habitability.

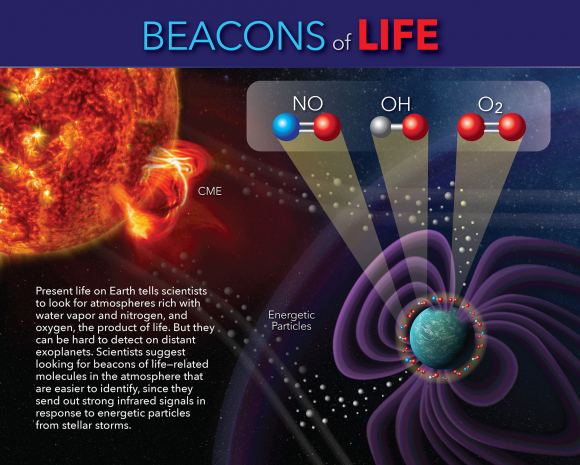

As scientists have come to understand, life takes a long time to get going. On Earth, it is estimated that the first microorganisms arose after 500 million years, and hydrothermal vents are believed to have played a key role in that process. It took another 2.5 billion years for the first multi-cellular life to evolve, and land-based plants and animals have only been around for the past 500 million years.

Knowing that moons like Enceladus – which has the necessary chemistry to support for life – has also had the necessary energy for billions of years is therefore very encouraging. One can only imagine what we will find once future missions begin inspecting its plumes more closely!

Further Reading: ESA, Nature Astronomy