If something called “Project METERON” sounds to you like a sinister project involving astronauts, robots, the International Space Station, and artificial intelligence, I don’t blame you. Because that’s what it is (except for the sinister part.) In fact, the Meteron Project (Multi-Purpose End-to-End Robotic Operation Network) is not sinister at all, but a friendly collaboration between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR.)

The idea behind the project is to place an artificially intelligent robot here on Earth under the direct control of an astronaut 400 km above the Earth, and to get the two to work together.

“Artificial intelligence allows the robot to perform many tasks independently, making us less susceptible to communication delays that would make continuous control more difficult at such a great distance.” – Neil Lii, DLR Project Manager.

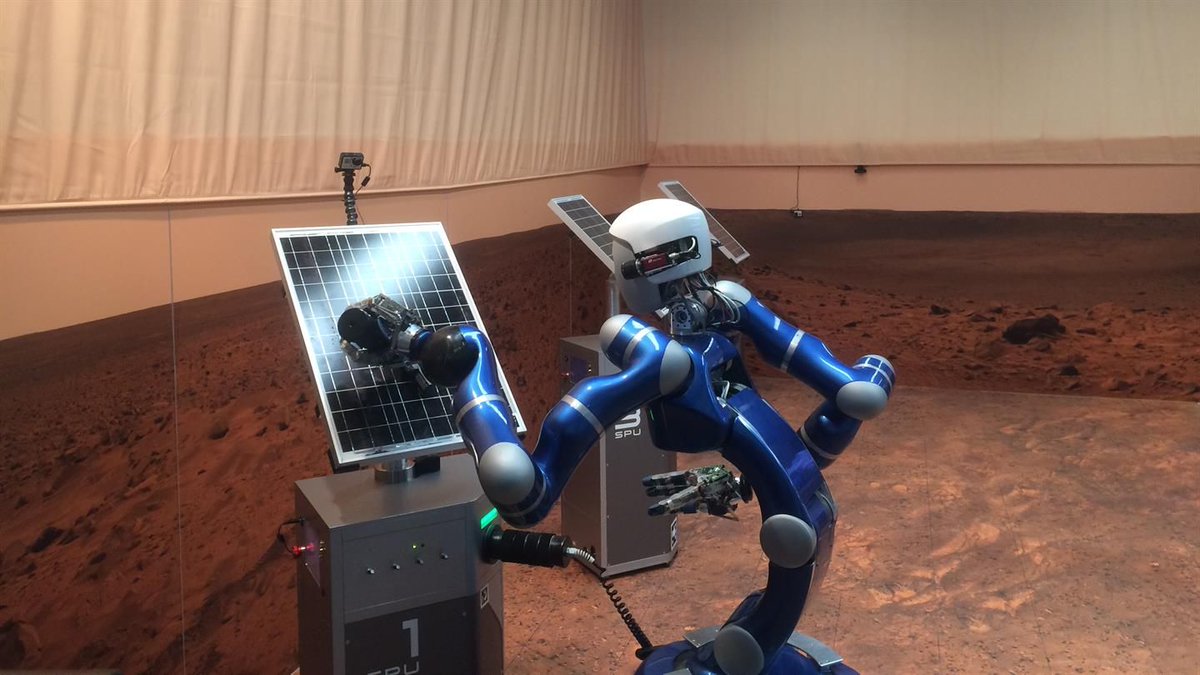

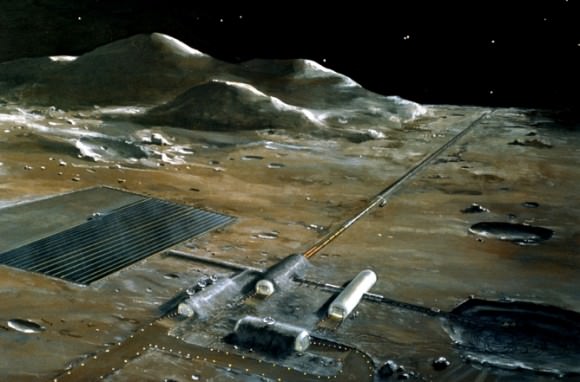

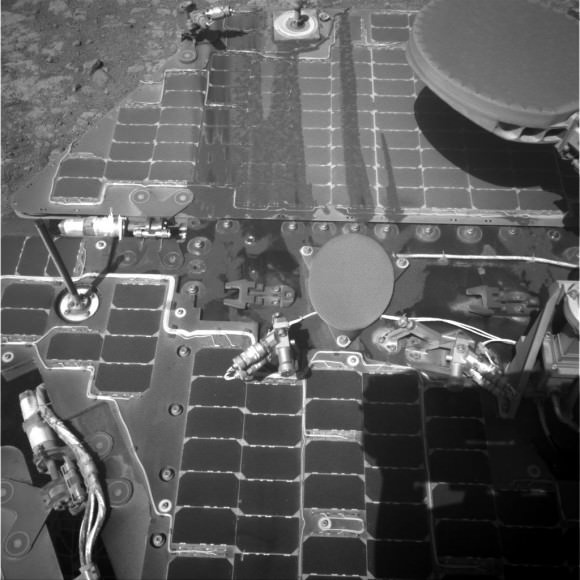

On March 2nd, engineers at the DLR Institute of Robotics and Mechatronics set up the robot called Justin in a simulated Martian environment. Justin was given a simulated task to carry out, with as few instructions as necessary. The maintenance of solar panels was the chosen task, since they’re common on landers and rovers, and since Mars can get kind of dusty.

The first test of the METERON Project was done in August. But this latest test was more demanding for both the robot and the astronaut issuing the commands. The pair had worked together before, but since then, Justin was programmed with more abstract commands that the operator could choose from.

American astronaut Scott Tingle issued commands to Justin from a tablet aboard the ISS, and the same tablet also displayed what Justin was seeing. The human-robot team had practiced together before, but this test was designed to push the pair into more challenging tasks. Tingle had no advance knowledge of the tasks in the test, and he also had no advance knowledge of Justin’s new capabilities. On-board the ISS, Tingle quickly realized that the panels in the simulation down here were dusty. They were also not pointed in the optimal direction.

This was a new situation for Tingle and for Justin, and Tingle had to choose from a range of commands on the tablet. The team on the ground monitored his choices. The level of complexity meant that Justin couldn’t just perform the task and report it completed, it meant that Tingle and the robot also had to estimate how clean the panels were after being cleaned.

“Our team closely observed how the astronaut accomplished these tasks, without being aware of these problems in advance and without any knowledge of the robot’s new capabilities,” says DLR engineer Daniel Leidner.

The next test will take place in Summer 2018 and will push the system even further. Justin will have an even more complex task before him, in this case selecting a component on behalf of the astronaut and installing it on the solar panels. The German ESA astronaut Alexander Gerst will be the operator.

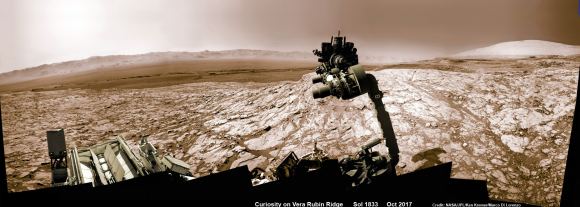

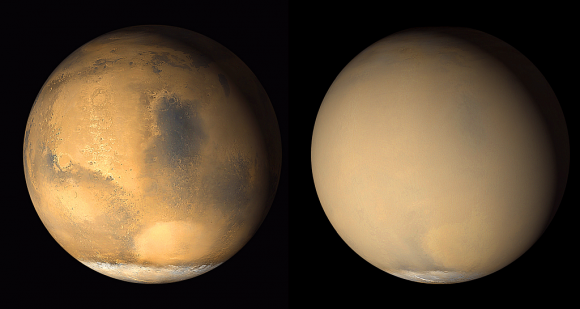

If the whole point of this is not immediately clear to you, think Mars exploration. We have rovers and landers working on the surface of Mars to study the planet in increasing detail. And one day, humans will visit the planet. But right now, we’re restricted to surface craft being controlled from Earth.

What METERON and other endeavours like it are doing, is developing robots that can do our work for us. But they’ll be smart robots that don’t need to be told every little thing. They are just given a task and they go about doing it. And the humans issuing the commands could be in orbit around Mars, rather than being exposed to all the risks on the surface.

“Artificial intelligence allows the robot to perform many tasks independently, making us less susceptible to communication delays that would make continuous control more difficult at such a great distance,” explained Neil Lii, DLR Project Manager. “And we also reduce the workload of the astronaut, who can transfer tasks to the robot.” To do this, however, astronauts and robots must cooperate seamlessly and also complement one another.

That’s why these tests are important. Getting the astronaut and the robot to perform well together is critical.

“This is a significant step closer to a manned planetary mission with robotic support,” says Alin Albu-Schäffer, head of the DLR Institute of Robotics and Mechatronics. It’s expensive and risky to maintain a human presence on the surface of Mars. Why risk human life to perform tasks like cleaning solar panels?

“The astronaut would therefore not be exposed to the risk of landing, and we could use more robotic assistants to build and maintain infrastructure, for example, with limited human resources.” In this scenario, the robot would no longer simply be the extended arm of the astronaut: “It would be more like a partner on the ground.”