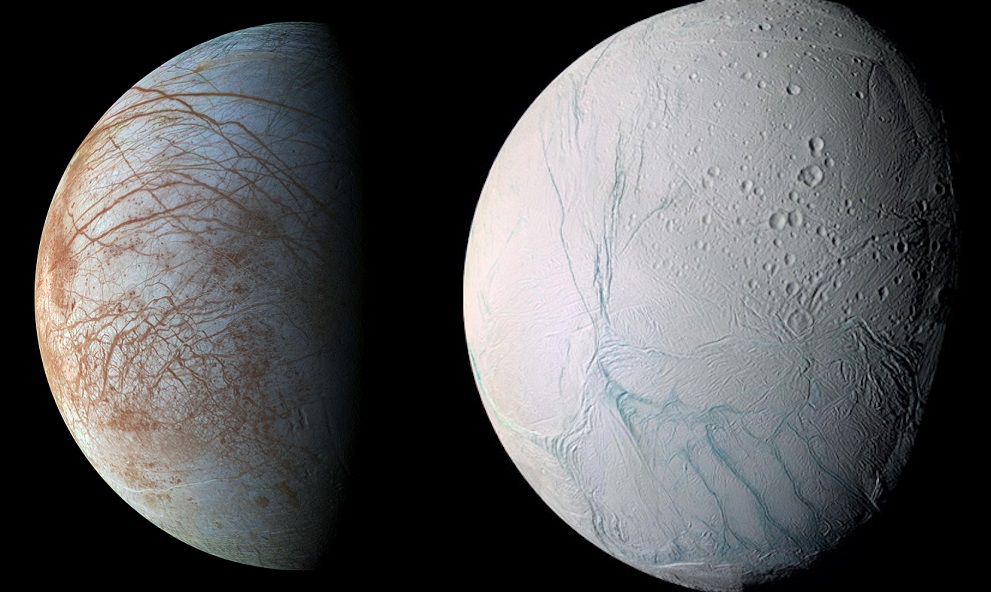

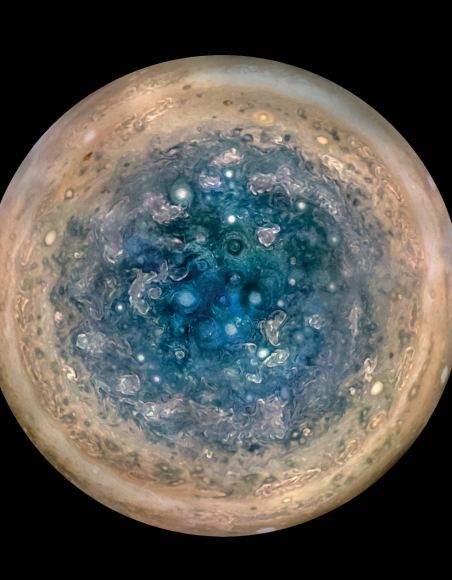

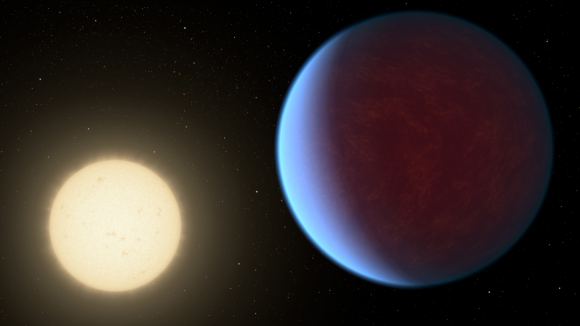

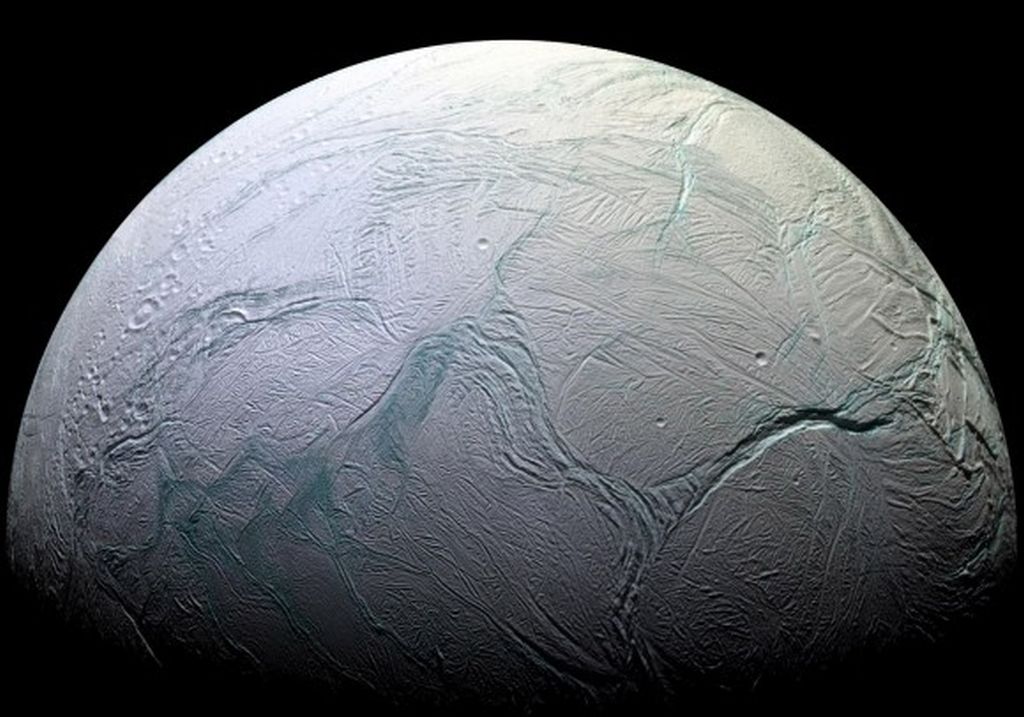

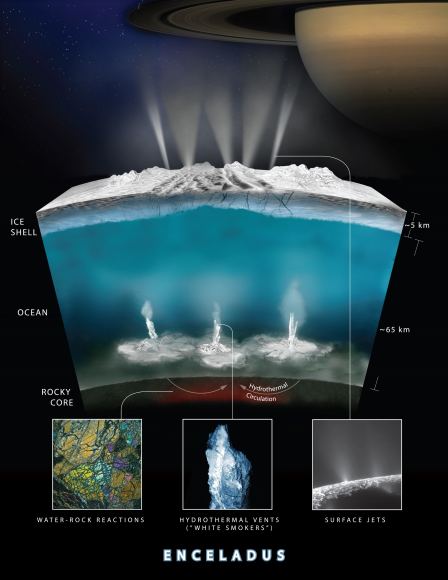

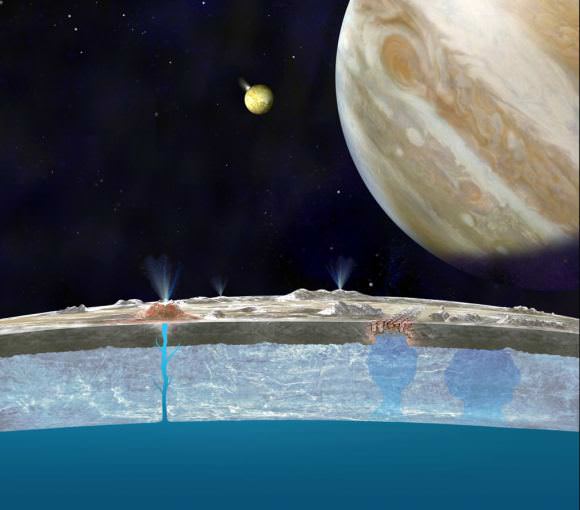

For decades, scientists have been speculating that life could exist in beneath the icy surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa. Thanks to more recent missions (like the Cassini spacecraft), other moons and bodies have been added to this list as well – including Titan, Enceladus, Dione, Triton, Ceres and Pluto. In all cases, it is believed that this life would exist in interior oceans, most likely around hydrorthermal vents located at the core-mantle boundary.

One problem with this theory is that in such undersea environments, life might have a hard time getting some of the key ingredients it would need to thrive. However, in a recent study – which was supported by the NASA Astrobiology Institute (NAI) – a team of researchers ventured that in the outer Solar System, the combination of high-radiation environments, interior oceans and hydrothermal activity could be a recipe for life.

The study, titled “The Possible Emergence of Life and Differentiation of a Shallow Biosphere on Irradiated Icy Worlds: The Example of Europa“, recently appeared in the scientific journal Astrobiology. The study was led by Dr. Michael Russell with the support of Alison Murray of the Desert Research Institute and Kevin Hand – also a researcher with NASA JPL.

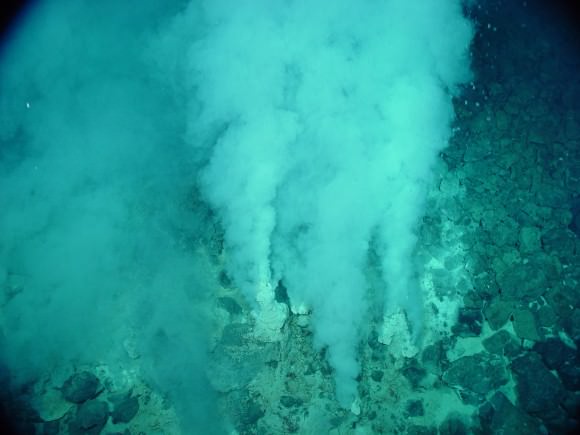

For the sake of their study, Dr. Russell and his colleagues considered how the interaction between alkaline hydrothermal springs and sea water is often considered to be how the key building blocks for life emerged here on Earth. However, they emphasize that this process was also dependent on energy provided by our Sun. The same process could have happened on moon’s like Europa, but in a different way. As they state in their paper:

“[T]he significance of the proton and electron flux must also be appreciated, since those processes are at the root of life’s role in free energy transfer and transformation. Here, we suggest that life may have emerged on irradiated icy worlds such as Europa, in part as a result of the chemistry available within the ice shell, and that it may be sustained still, immediately beneath that shell.”

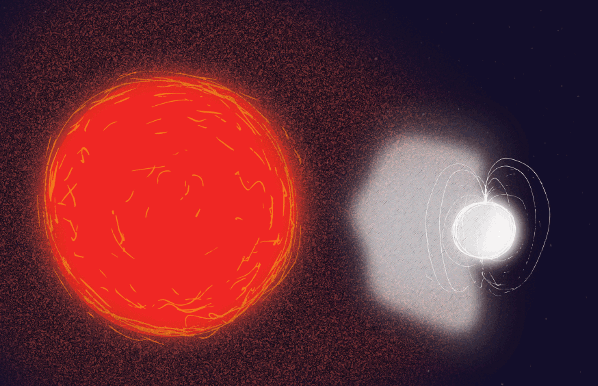

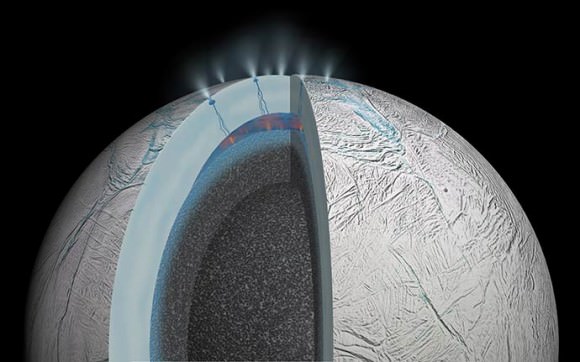

In the case of moon’s like Europa, hydrothermal springs would be responsible for churning up all the necessary energy and ingredients for organic chemistry to take place. Ionic gradients, such as oxyhydroxides and sulfides, could drive the key chemical processes – where carbon dioxide and methane are hydrogenated and oxidized, respectively – which could lead to the creation of early microbial life and nutrients.

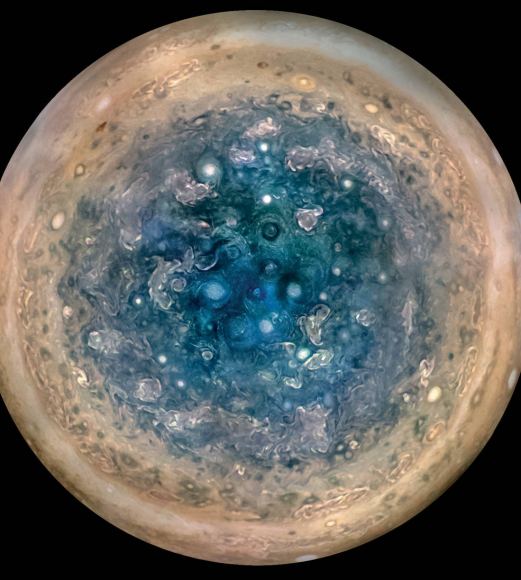

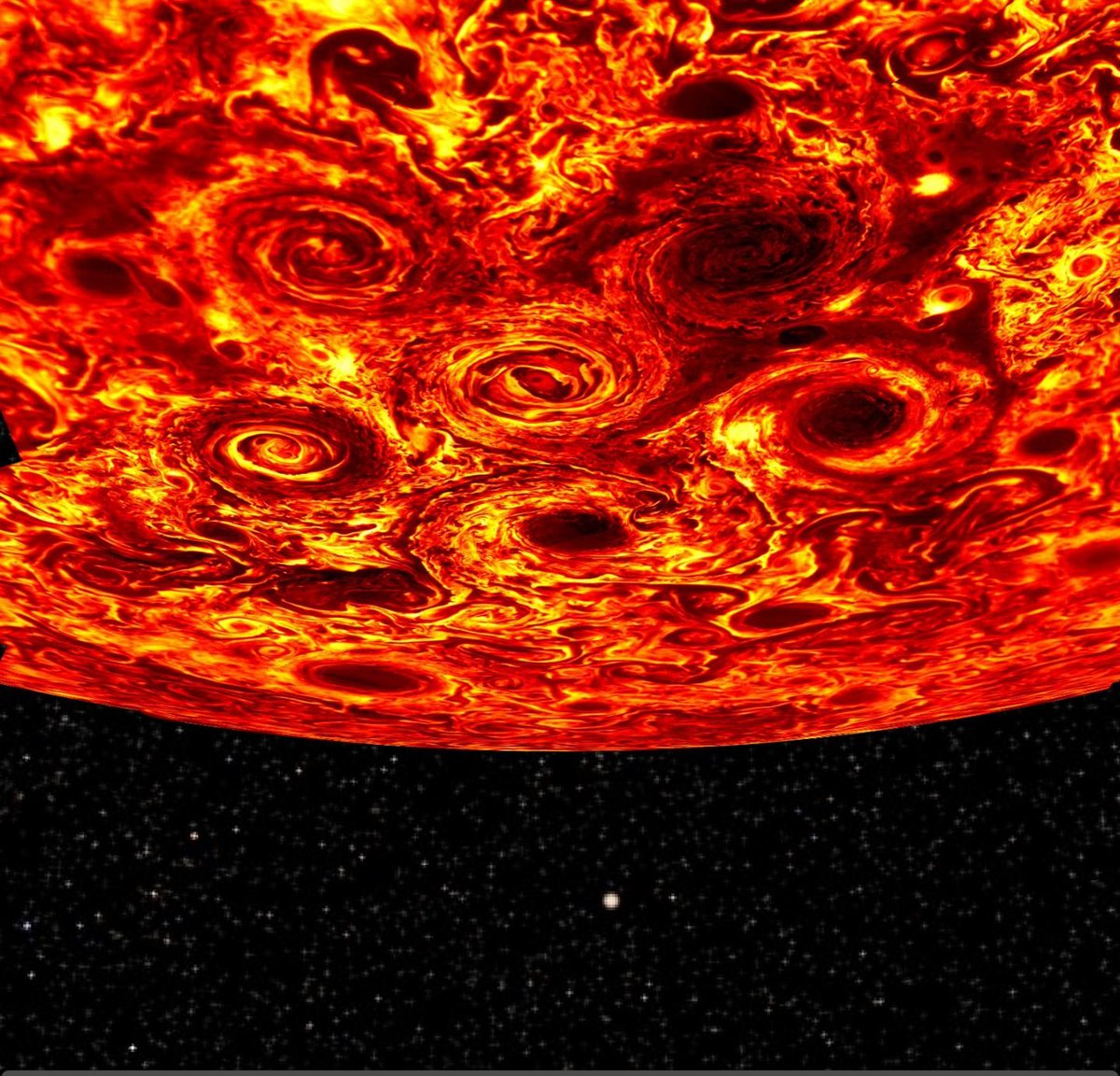

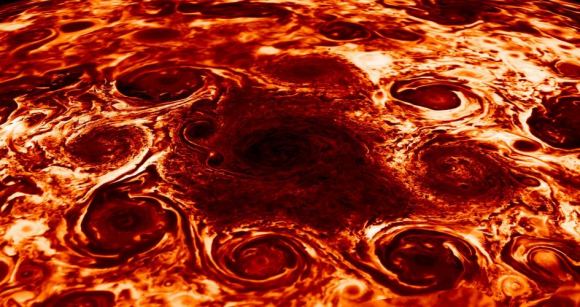

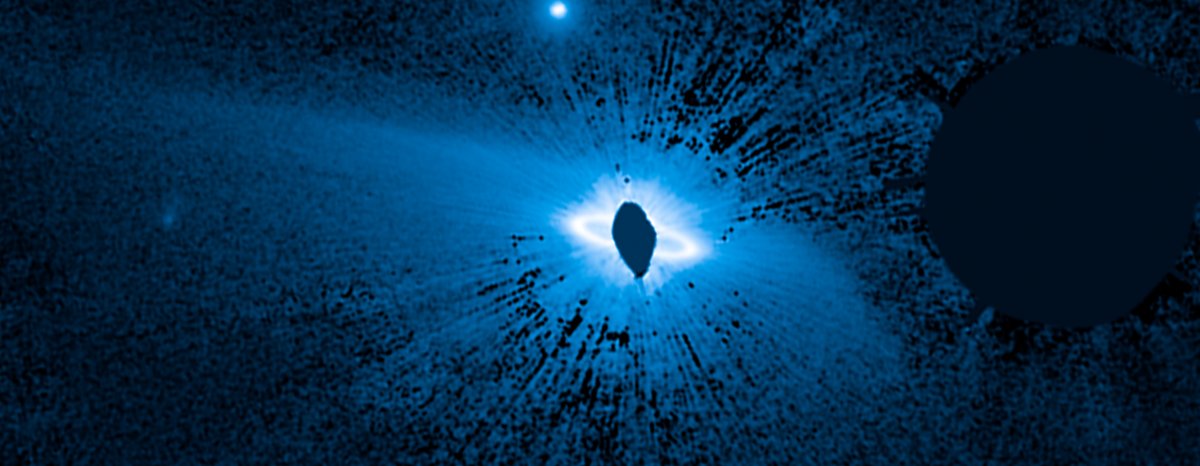

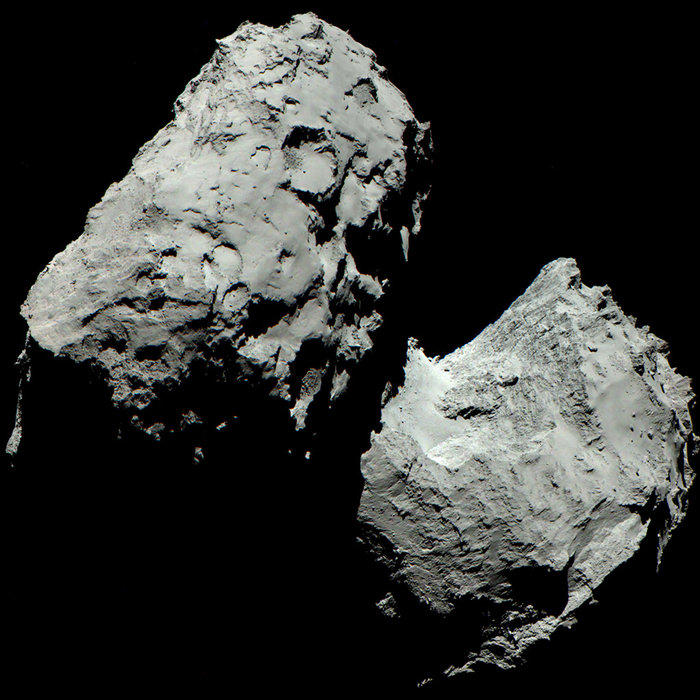

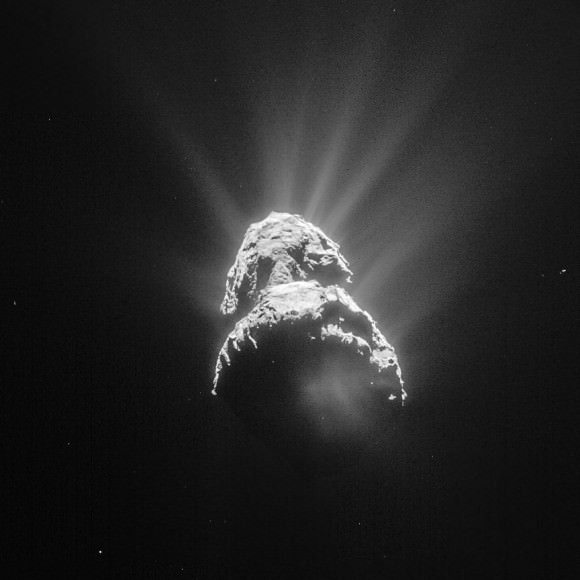

At the same time, the heat from hydrothermal vents would push these microbes and nutrients upwards towards the icy crust. This crust is regularly bombarded by high-energy electrons created by Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field, a process which creates oxidants. As scientists have known for some time from surveying Europa’s crust, there is a process of exchange between the moon’s interior ocean and its surface.

As Dr. Russell and his colleagues indicate, this action would most likely involve the plume activity that has been observed on Europa’s surface, and could lead to a network of ecosystems on the underside of Europa’s icy crust:

“Models for transport of material within Europa’s ocean indicate that hydrothermal plumes could be well constrained within the ocean (primarily by the Coriolis force and thermal gradients), leading to effective delivery through the ocean to the ice-water interface. Organisms fortuitously transported from hydrothermal systems to the ice-water interface along with unspent fuels could potentially access a larger abundance of oxidants directly from the ice. Importantly, oxidants might only be available where the ice surface has been driven to the base of the ice shell.”

As Dr. Russel indicated in an interview with Astrobiology Magazine, microbes on Europa could reach densities similar to what has been observed around hydrothermal vents here on Earth, and may bolster the theory that life on Earth also emerged around such vents. “All the ingredients and free energy required for life are all focused in one place,” he said. “If we were to find life on Europa, then that would strongly support the submarine alkaline vent theory.”

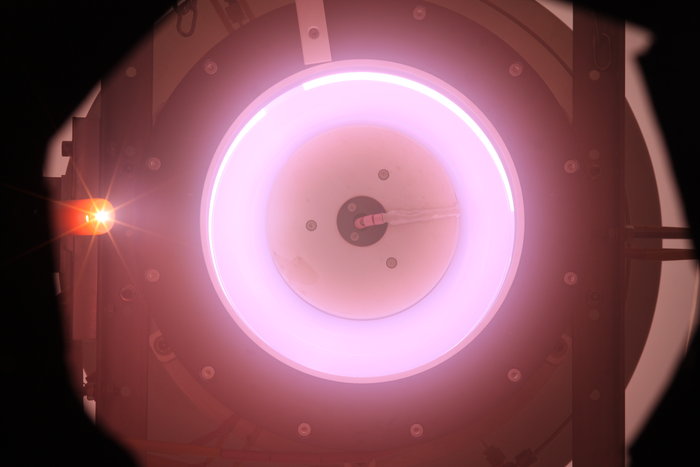

This study is also significant when it comes to mounting future missions to Europa. If microbial ecosystems exist on the undersides of Europa’s icy crust, then they could be explored by robots that are able to penetrate the surface, ideally by traveling down a plume tunnel. Alternately, a lander could simply position itself near an active plume and search for signs of oxidants and microbes coming up from the interior.

Similar missions could also be mounted to Enceladus, where the presence of hydrothermal vents has already been confirmed thanks to the extensive plume activity observed around its southern polar region. Here too, a robotic tunneler could enter surface fissures and explore the interior to see if ecosystems exist on the underside of the moon’s icy crust. Or a lander could position itself near the plumes and examine what is being ejected.

Such missions would be simpler and less likely to cause contamination than robotic submarines designed to explore Europa’s deep ocean environment. But regardless of what form a future mission to Europa, Enceladus, or other such bodies takes, it is encouraging to know that any life that may exist there could be accessible. And if these missions can sniff it out, we will finally know that life in the Solar System evolved in places other than Earth!

Further Reading: Astrobiology Magazine, Astrobiology