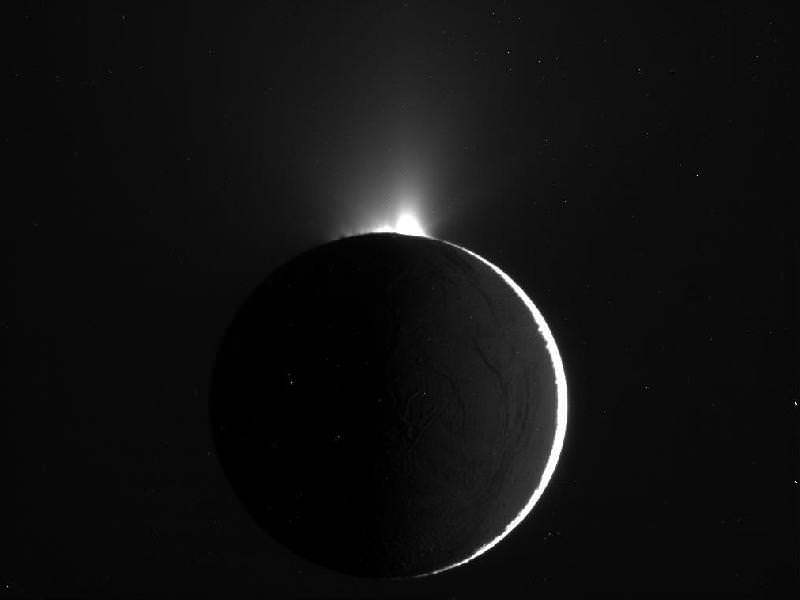

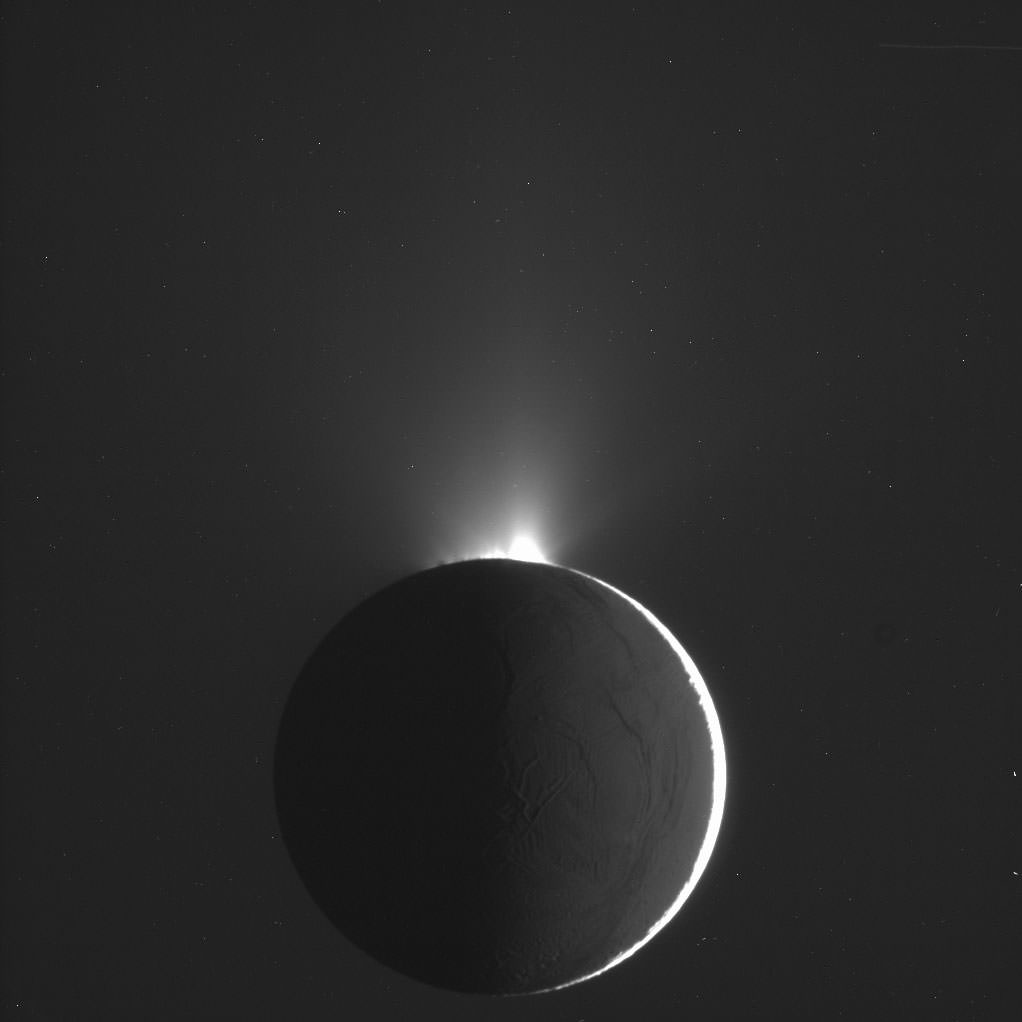

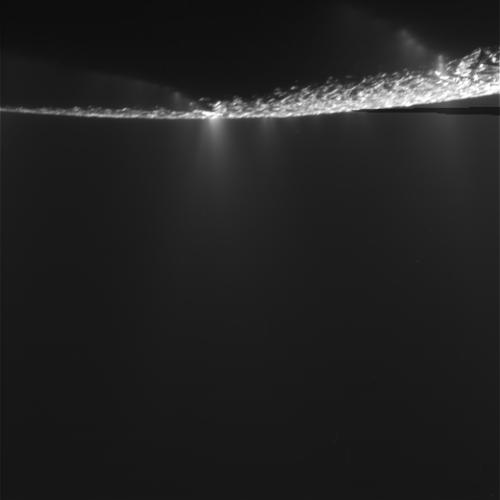

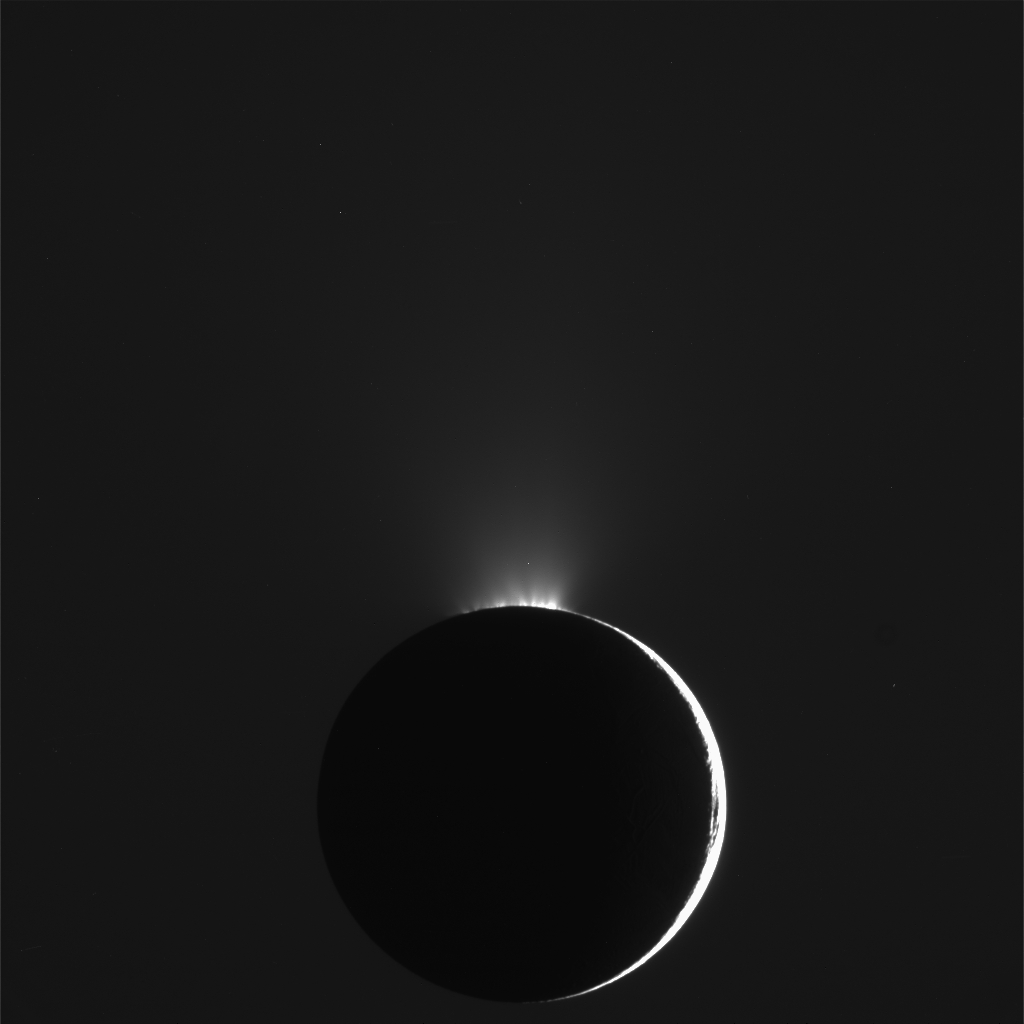

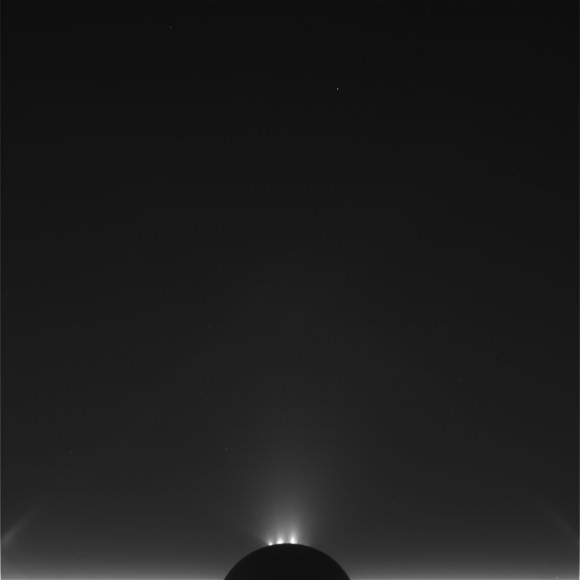

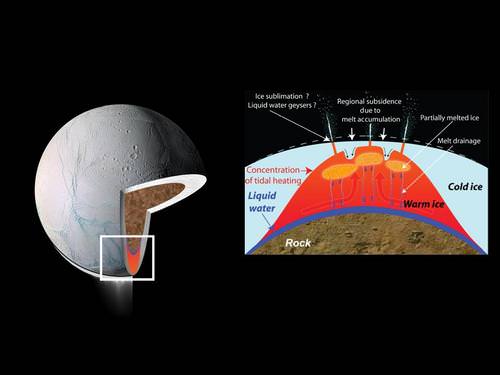

Caption: Geysers on Enceladus. Credit: NASA, JPL, Space Science Institute

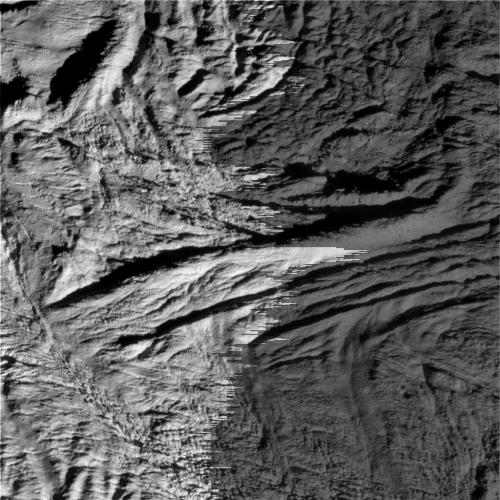

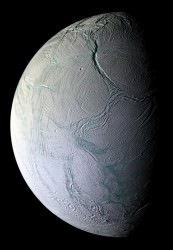

One of the most exciting but unexpected discoveries of the Cassini mission is seeing the activity taking place on Saturn’s small moon Enceladus. Between the active geysers, the unusual “tiger stripes” and the surprisingly young surface near the moon’s south pole, Enceladus has surprised scientists with almost all the images and data the gathered by the spacecraft. But is the moon always active, or are we just in the right place at the right time, lucky to be catching it during an active phase? A recent paper outlines a model in which the kind of geologic eruptions now visible on Enceladus only occur every billion years or so.

“Cassini appears to have caught Enceladus in the middle of a burp,” said Francis Nimmo, a planetary scientist at the University of California Santa Cruz. “These tumultuous periods are rare and Cassini happens to have been watching the moon during one of these special epochs.”

Nimmo and co-author Craig O’Neill of Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia propose that blobs of warm ice that periodically rise to the surface and churn the icy crust on Saturn’s moon Enceladus explain the quirky heat behavior and intriguing surface of the moon’s south polar region.

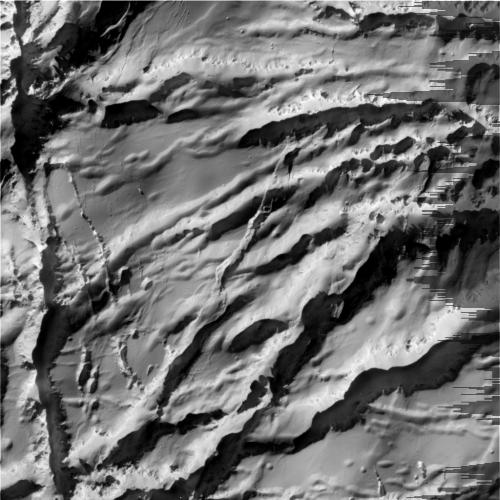

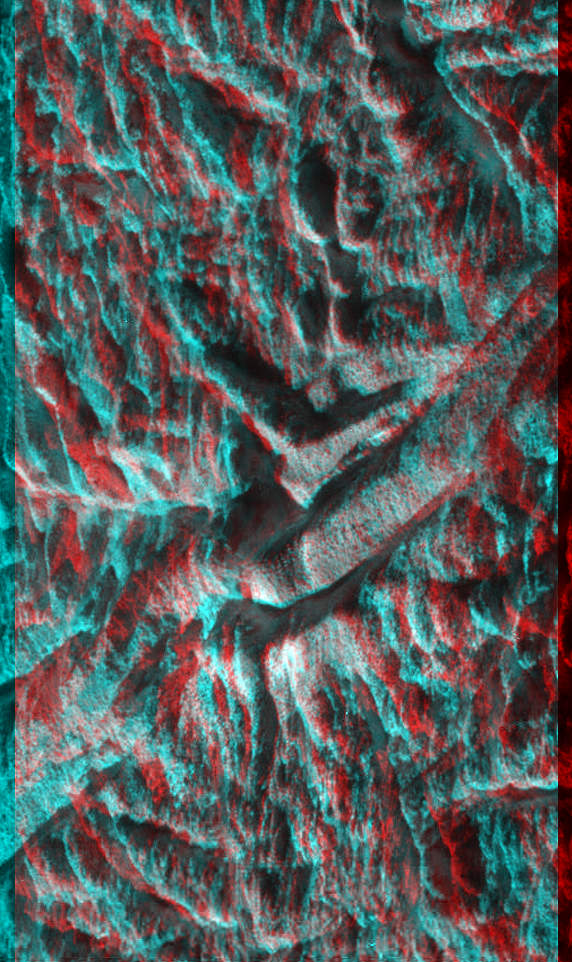

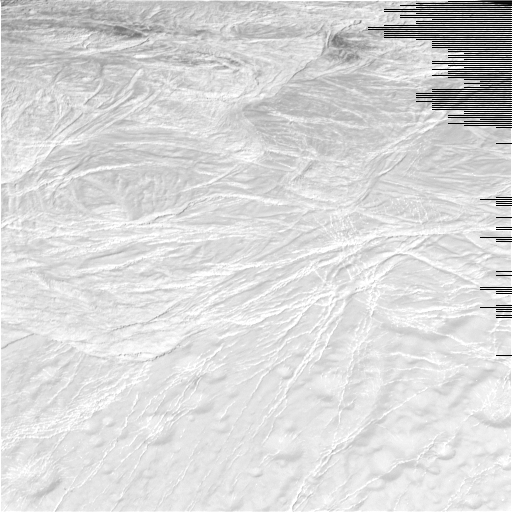

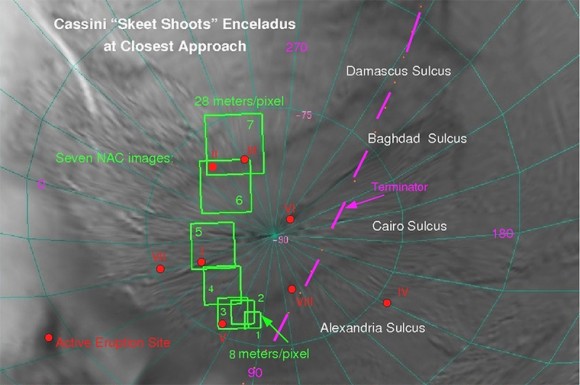

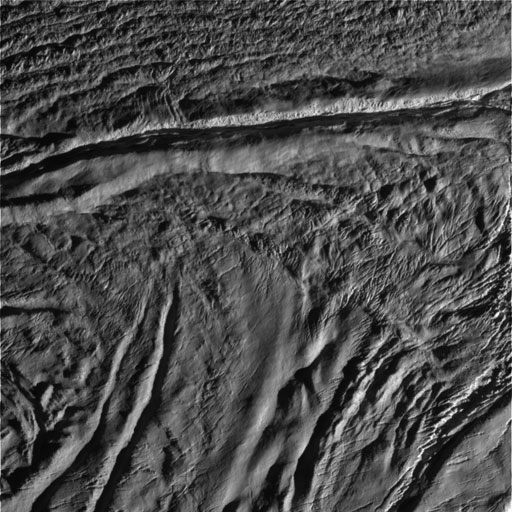

The most interesting features by far in the south polar region of Enceladus are the fissures known as “tiger stripes” that spray water vapor and other particles out from the moon. While Nimmo and O’Neill’s model doesn’t link the churning and resurfacing directly to the formation of fissures and jets, it does fill in some of the blanks in the region’s history.

“This episodic model helps to solve one of the most perplexing mysteries of Enceladus,” said Bob Pappalardo, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., of the research done by his colleagues. “Why is the south polar surface so young? How could this amount of heat be pumped out at the moon’s south pole? This idea assembles the pieces of the puzzle.”

But not everyone is convinced this model answers all the questions about Enceladus. Carolyn Porco, who leads the imaging team for Cassini said via Twitter regarding this paper, “Beware! Several different models out there say different things.”

About four years ago, Cassini’s composite infrared spectrometer instrument detected a heat flow in the south polar region of at least 6 gigawatts, the equivalent of at least a dozen electric power plants. This is at least three times as much heat as an average region of Earth of similar area would produce, despite Enceladus’ small size. The region was also later found by Cassini’s ion and neutral mass spectrometer instrument to be swiftly expelling argon, which comes from rocks decaying radioactively and has a well-known rate of decay.

Calculations told scientists it would be impossible for Enceladus to have continually produced heat and gas at this rate. Tidal movement – the pull and push from Saturn as Enceladus moves around the planet – cannot explain the release of so much energy.

The surface ages of different regions of Enceladus also show great diversity. Heavily cratered plains in the northern part of the moon appear to be as old as 4.2 billion years, while a region near the equator known as Sarandib Planitia is between 170 million and 3.7 billion years old. The south polar area, however, appears to be less than 100 million years old, possibly as young as 500,000 years.

O’Neill had originally developed the model for the convection of Earth’s crust. For the model of Enceladus, which has a surface completely covered in cold ice that is fractured by the tug of Saturn’s gravitational pull, the scientists stiffened up the crust. They picked a strength somewhere between that of the malleable tectonic plates on Earth and the rigid plates of Venus, which are so strong, it appears they never get sucked down into the interior.

Their model showed that heat building up from the interior of Enceladus could be released in episodic bubbles of warm, light ice rising to the surface, akin to the rising blobs of heated wax in a lava lamp. The rise of the warm bubbles would send cold, heavier ice down into the interior. (Warm is, of course, relative. Nimmo said the bubbles are probably just below freezing, which is 273 degrees Kelvin or 32 degrees Fahrenheit, whereas the surface is a frigid 80 degrees Kelvin or -316 degrees Fahrenheit.)

The model fits the activity on Enceladus when the churning and resurfacing periods are assumed to last about 10 million years, and the quiet periods, when the surface ice is undisturbed, last about 100 million to two billion years. Their model suggests the active periods have occurred only 1 to 10 percent of the time that Enceladus has existed and have recycled 10 to 40 percent of the surface. The active area around Enceladus’s south pole is about 10 percent of its surface.

Source: JPL