Growing up, my sister played video games and I read books. Now that she has a one-year-old daughter we constantly argue over how her little girl should spend her time. Should she read books in order to increase her vocabulary and stretch her imagination? Or should she play video games in order to strengthen her hand-eye coordination and train her mind to find patterns?

I like to believe that I did so well in school because of my initial unadorned love for books. But I might be about to lose that argument as gamers prove their value in science and more specifically astronomy.

Take a quick look through Zooniverse and you’ll be amazed by the number of Citizen Science projects. You can explore the surface of the moon in Moon Zoo, determine how galaxies form in Galaxy Zoo and search for Earth-like planets in Planet Hunters.

In 2011 two citizen scientists made big news when they discovered two exoplanet candidates — demonstrating that human pattern recognition can easily compliment the powerful computer algorithms created by the Kepler team.

But now we’re introducing yet another Citizen Science project: Disk Detective.

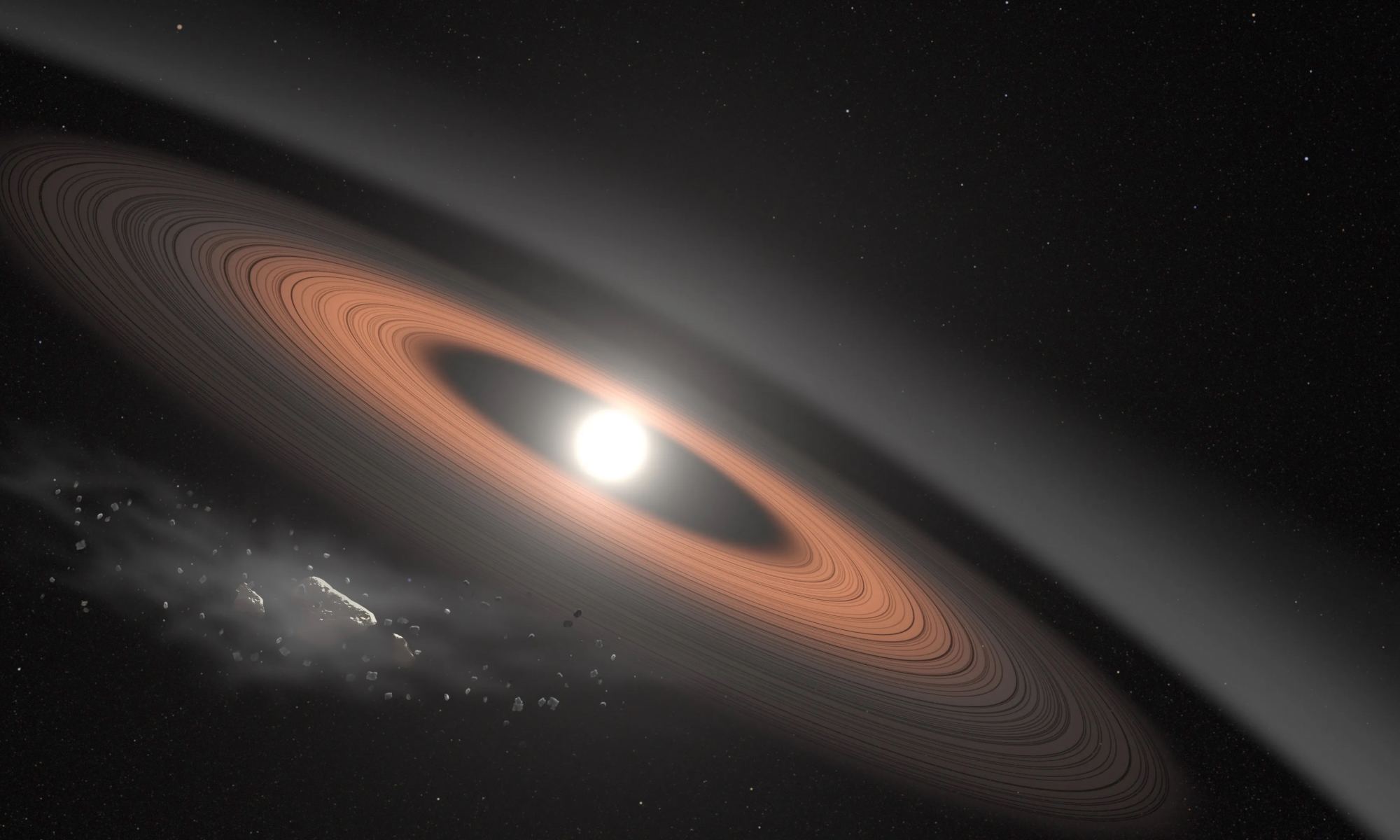

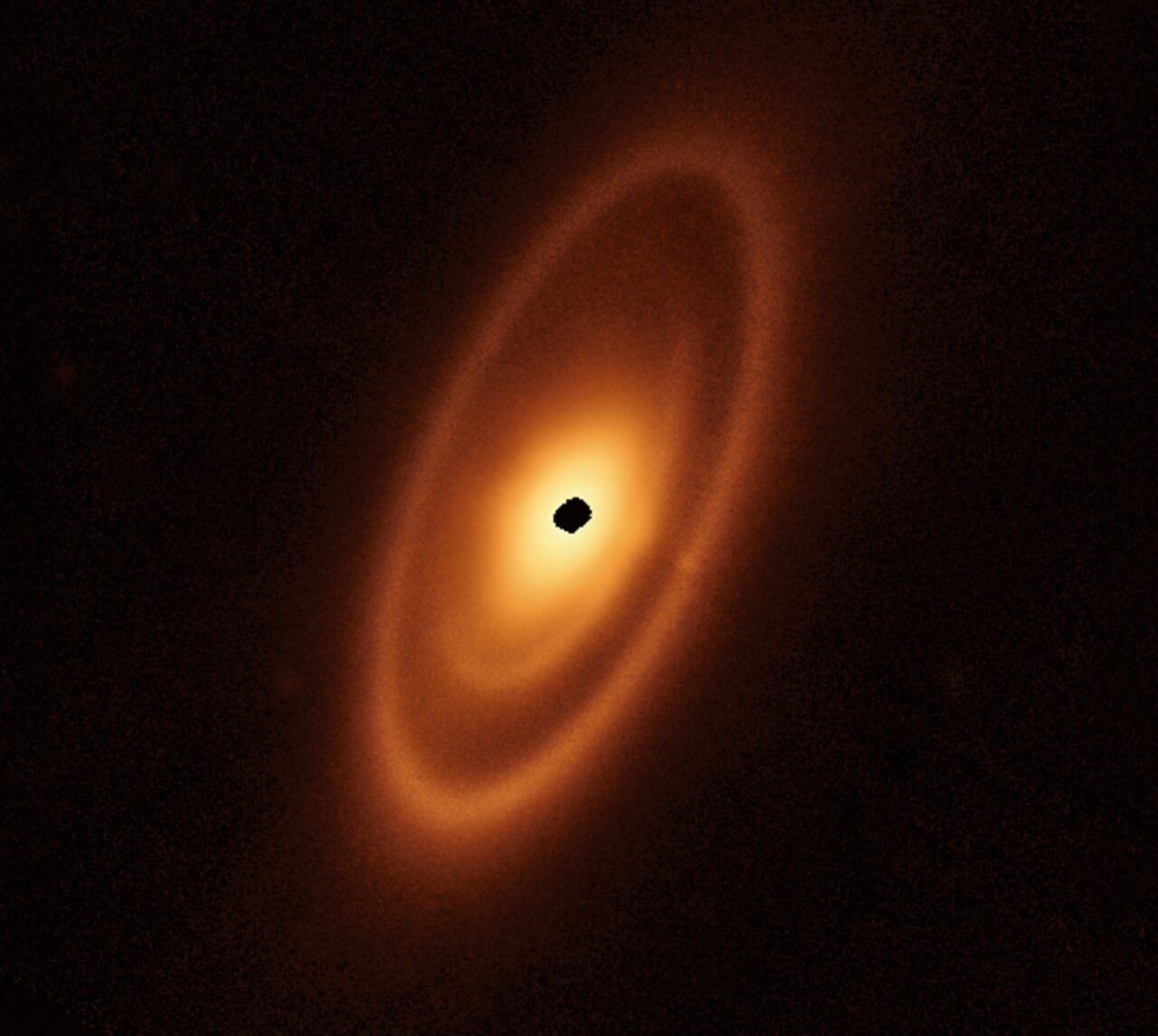

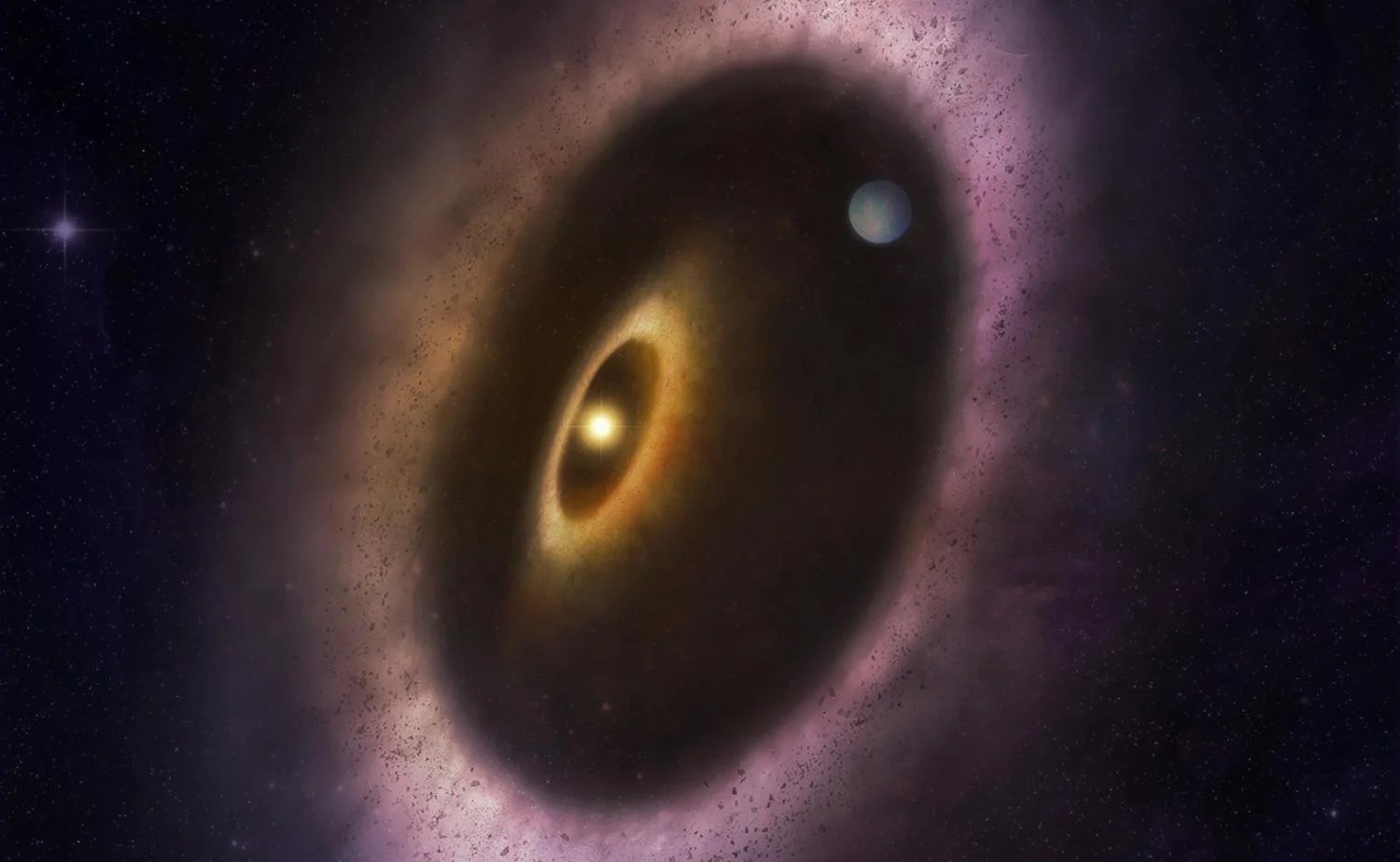

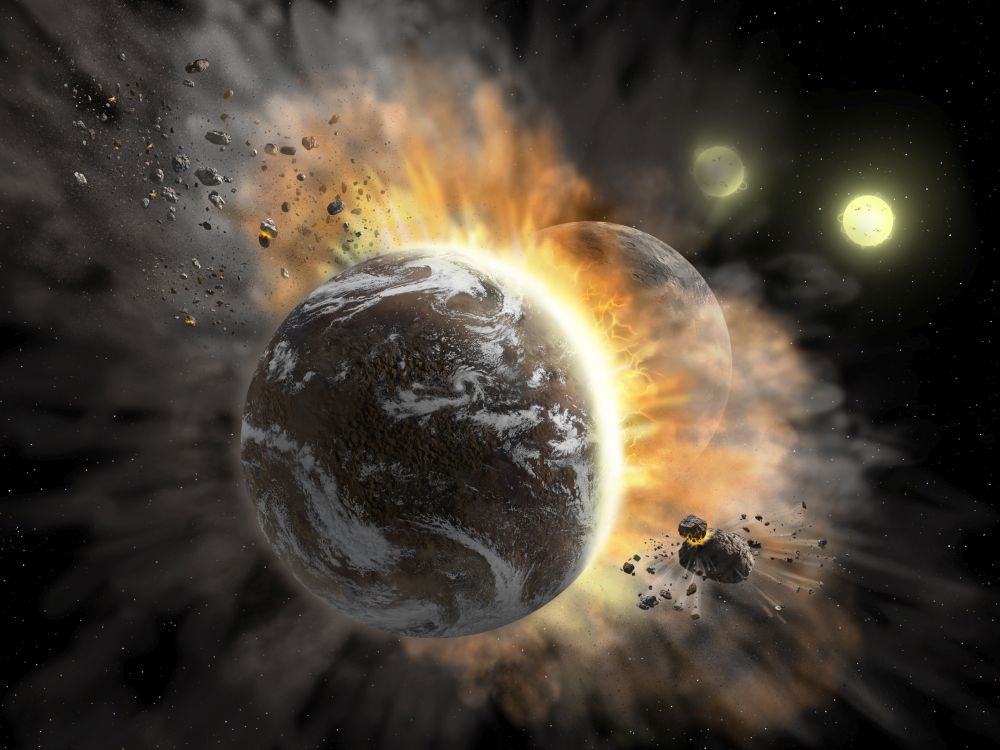

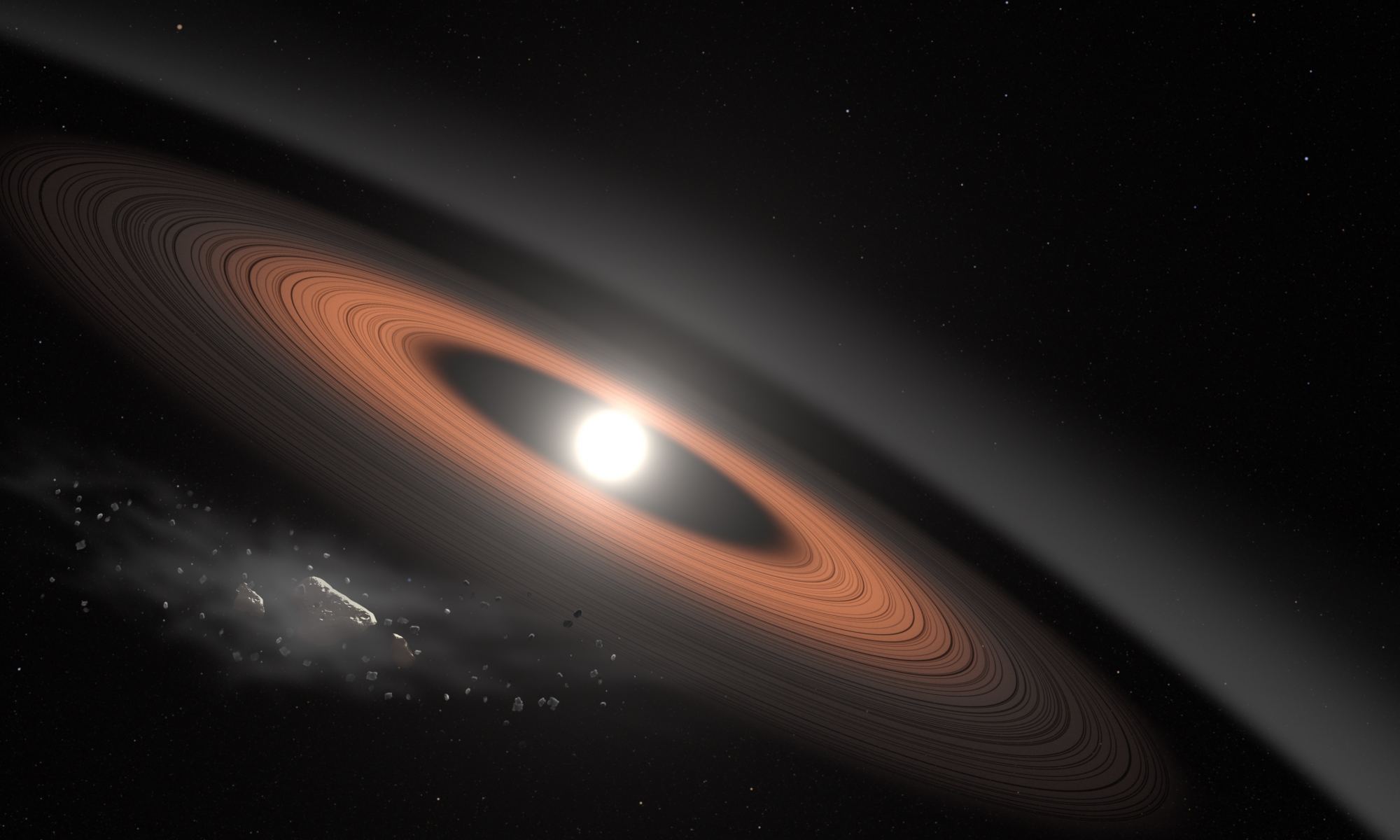

Planets form and grow within dusty circling planes of gas that surround young stars. However, there are many outstanding questions and details within this process that still elude us. The best way to better understand how planets form is to directly image nearby planetary nurseries. But first we have to find them.

“Through Disk Detective, volunteers will help the astronomical community discover new planetary nurseries that will become future targets for NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and its successor, the James Webb Space Telescope,” said the chief scientist for NASA Goddard’s Sciences and Exploration Directorate, James Garvin, in a press release.

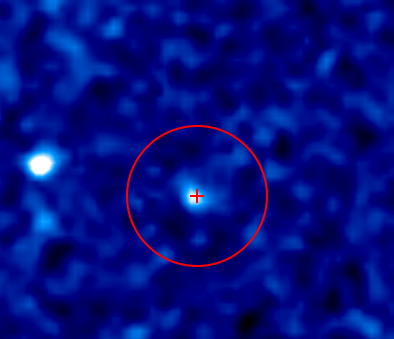

NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) scanned the entire sky at infrared wavelengths for a year. It took detailed measurements of more than 745 million objects.

Astronomers have used complex computer algorithms to search this vast amount of data for objects that glow bright in the infrared. But now they’re calling on your help. Not only do planetary nurseries glow in the infrared but so do galaxies, interstellar dust clouds and asteroids.

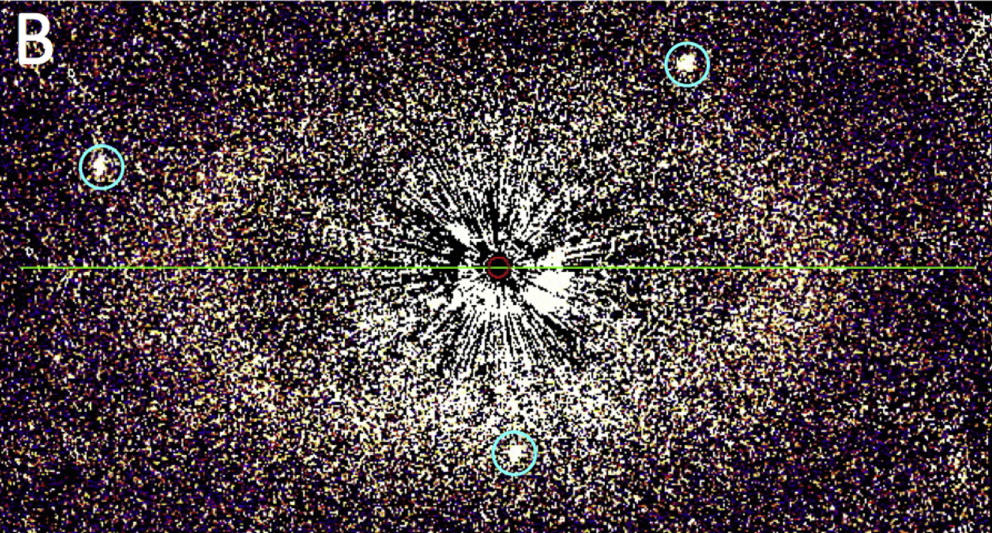

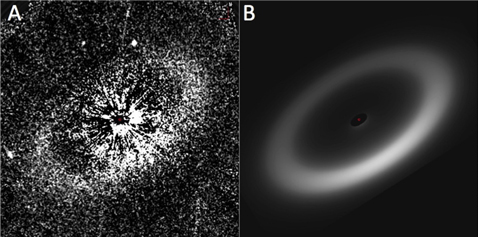

While there’s likely to be thousands of planetary nurseries glowing bright in the data, we have to separate them from everything else. And the only way to do this is to inspect every single image by eye — a monumental challenge for any astronomer — hence the invention of Disk Detective.

Brief animations allow the user to help classify the object based on relatively simple criteria, such as whether or not the object is round or if there are multiple objects.

“Disk Detective’s simple and engaging interface allows volunteers from all over the world to participate in cutting-edge astronomy research that wouldn’t even be possible without their efforts,” said Laura Whyte, director of Citizen Science at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, Ill.

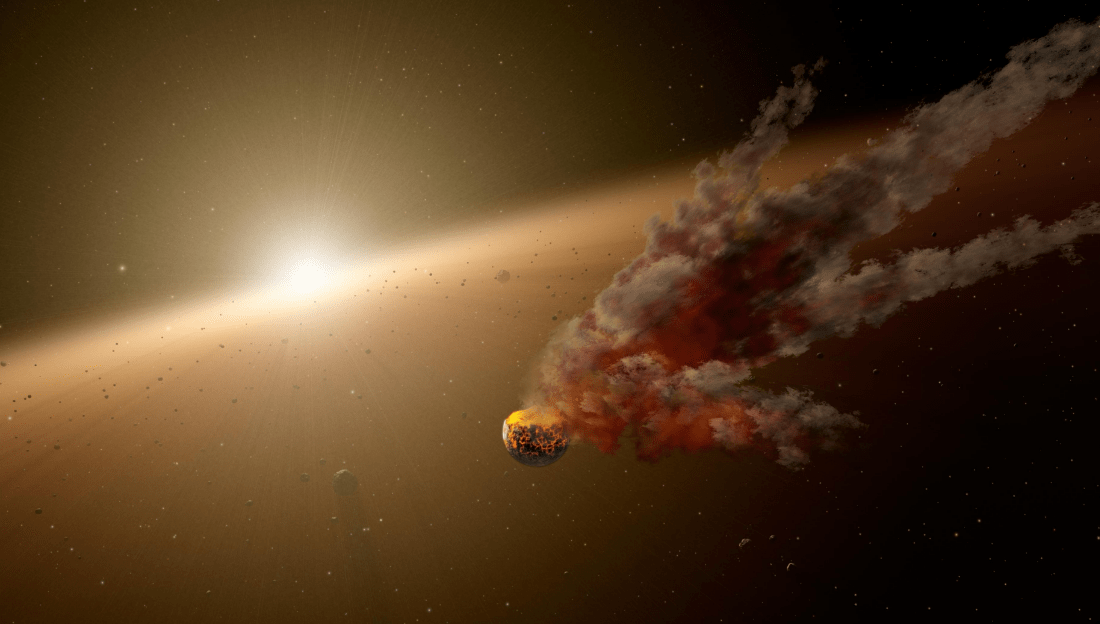

The project is hoping to find two types of developing planetary environments, distinguished by their age. The first, known as a young stellar object disk is, well, young. It’s less than 5 million years old and contains large quantities of gas. The second, known as a debris disk, is older than 5 million years. It contains no gas but instead belts of rocky or icy debris similar to our very own asteroid and Kupier belts.

So what are you waiting for? Head to Disk Detective and help astronomers understand how complex worlds form in dusty disks of gas. The book will be there when you get back.

The original press release may be found here.