Black Holes? Dark Energy? Dark Matter? Alien Life? What are the biggest mysteries that still exist out there for us to figure out?

“The more I learn, the more I realize how much I don’t know.” These are the words of Albert Einstein. I assume he was talking about Minecraft, but I guess it applies to the Universe too.

There are many examples: astronomers try to discover the rate of the expansion of the Universe, and learn a dark energy is accelerating its expansion. NASA’s Cassini spacecraft finally images Saturn’s moon Iapetus, and finds a strange equatorial ridge – how the heck did that get there? Did the Celestials forget to trim it when it came out of the packaging?

There have always been, and, let’s go as far as to say that there always will be, mysteries in astronomy. Although the nature of the mysteries may change, the total number is always going up.

Hundreds of years ago, people wanted to know how the planets moved through sky (conservation of angular momentum), how old the Earth was (4.54 billion years), or what kept the Moon from flying off into space (gravity). Just a century ago, astronomers weren’t sure what galaxies were (islands of stars), or how the Sun generated energy (nuclear fusion). And just a few decades ago, we didn’t know what caused quasars (feeding supermassive black holes), or how old the Universe was (13.8 billion years). Each of these mysteries has been solved, or at least, we’ve a got a pretty good understanding of what’s going on.

Science continues to explore and seek answers to the mysteries we have, and as it does it opens up new brand doors. Fortunately for anyone who’s thinking of going into astronomy as a career, there are a handful of really compelling mysteries to explore right now:

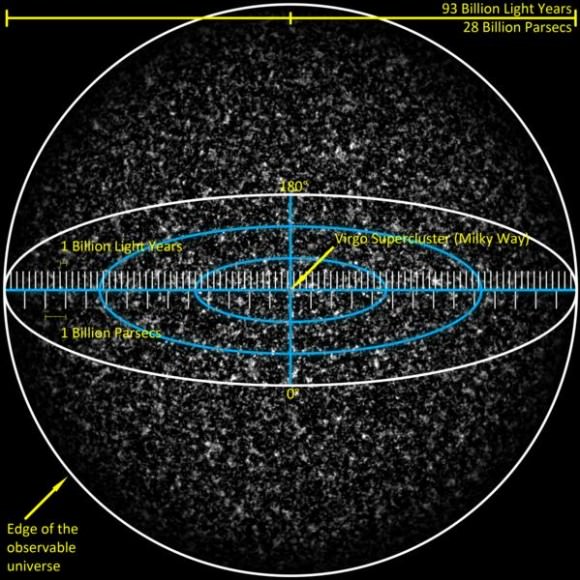

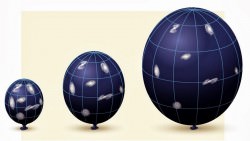

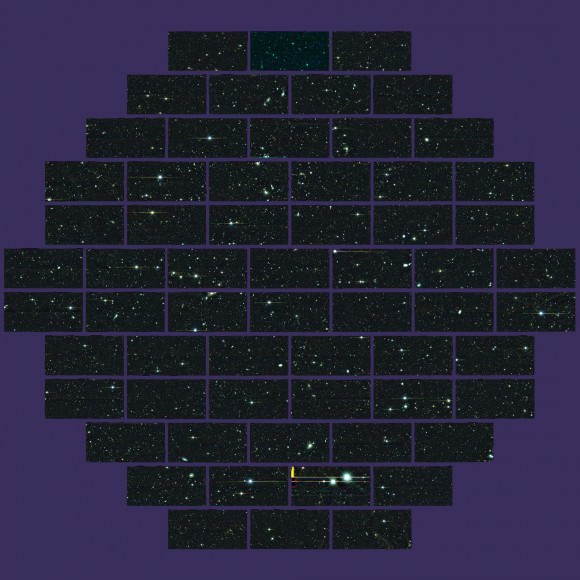

Is the Universe finite or infinite? We can see light that left shortly after the Big Bang, 13.8 billion years in all directions. And the expansion of the Universe has carried these regions more than 45 billion light-years away from us. But the Universe is probably much larger than that, and may be even infinite.

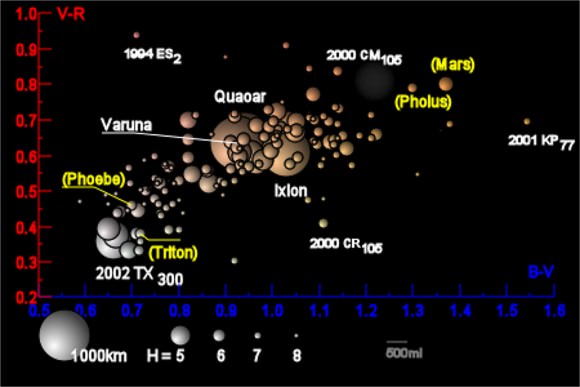

What is dark matter? Thanks to gravitational lensing, astronomers can perceive vast halos of invisible material around all galaxies. But what is this stuff, and why doesn’t it interact with any other matter?

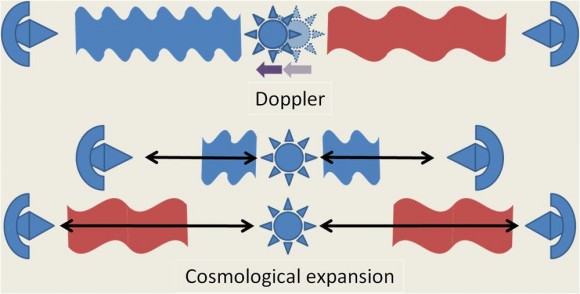

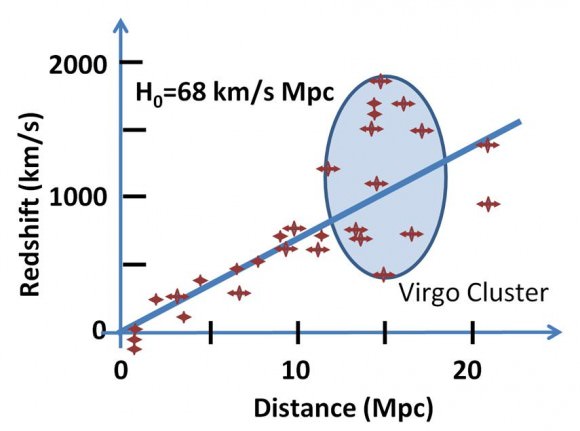

What is dark energy? When trying to discover the expansion rate of the Universe, astronomers discovered that the expansion is actually accelerating? Why is this happening? Is something causing this force, or do we just not understand gravity at the largest scales?

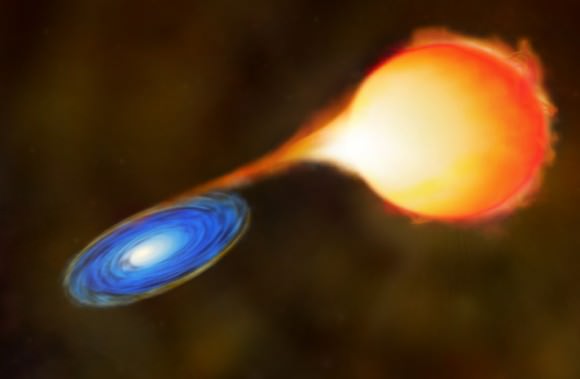

There are supermassive black holes at the heart of pretty much every galaxy. Did these supermassive black holes form first, and then the galaxies around them? Or was it the other way around?

The Big Bang occurred 13.8 billion years ago, and the expansion of the Universe has continued ever since. But what came before the Big Bang? In fact, what even caused the Big Bang? Has it been Big Bangs over and over again?

Are we alone in the Universe? Is there life on any other world or star system? And is anyone out there we could talk to?

Shortly after the Big Bang, incomprehensible amounts of matter and antimatter annihilated each other. But for some reason, there was a slightly higher ratio of matter – and so we have a matter dominated Universe. Why?

Is this the only Universe? Is there a multiverse of universes out there? How do I get to the Whedonverse?

In the distant future, after all the stars are dead and gone, maybe protons themselves will decay and there will be nothing left but energy. Physicists haven’t been able to catch a proton decaying yet. Will the ever?

And these are just some of the big ones. There are hundreds, thousands, millions of unanswered questions. The more we learn, the more we discover how little we actually understand.

Whenever we do a video about concepts in astronomy where we have a basic understanding, like gravity, evolution, or the Big Bang, trolls show up and say that scientists are so arrogant. That they think they know everything. But scientists don’t know everything, and they’re willing to admit when something is a mystery. When the answer to the question is: I don’t know.

What’s your favorite unanswered question in space and astronomy? Give us your best mystery in the comments below.