Artist concept of a previous multi-planet solar system found by the Kepler spacecraft. Credit: NASA/Tim Pyle

Most planetary systems found by astronomers so far are quite different than our own. Many have giant planets whizzing around in a compact configuration, very close to their star. An extreme case in point is a newly found solar system that was announced on October 15, 2012 which packs five — count ‘em — five planets into a region less than one-twelve the size of Earth’s orbit!

“This is an extreme example of a compact solar system,” said researcher Darin Ragozzine from the University of Florida, speaking at a press conference at the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences meeting. “If we can understand this one, hopefully we can understand how these types of systems form and why most known planetary systems appear different from our own solar system.”

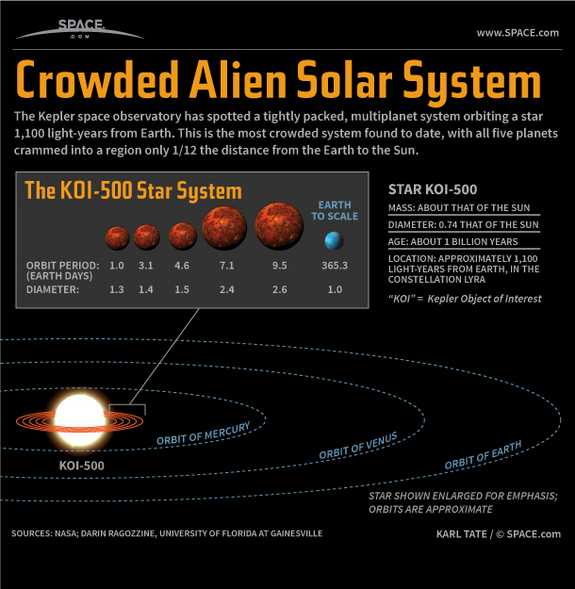

This new system, currently named KOI-500, was found with data from the Kepler planet-finding spacecraft, and Ragozzine said astronomers have now uncovered a new realm of exo-planetary systems.

“The real exciting thing is that Kepler has found hundreds of stars with multiple transiting planets,” he said. “These are the most information-rich systems, as they can tell you not only about the planets, but also the architecture of how solar systems are put together.”

The fact that almost all solar systems found so far are vastly different than our own has astronomers wondering if we are, in fact, the oddballs. A study from 2010 concluded that only about 10 – 15 percent of stars in the Universe host systems of planets like our own, with terrestrial planets nearer the star and several gas giant planets in the outer part of the solar system.

Part of the reason our dataset of exoplanets is skewed with planets that are close to the star is because currently, that is all we are capable of detecting.

But the surprising new population of planetary systems discovered in the Kepler data that contain several planets packed in a tiny space around their host stars does give credence to the thinking that our solar system may be somewhat unique.

However, perhaps KOI-500 used to be more like our solar system.

“From the architecture of this planetary system, we infer that these planets did not form at their current locations,” Ragozzine said. “The planets were originally more spread out and have ‘migrated’ into the ultra-compact configuration we see today.”

There are several theories about the formation of the large planets in our outer solar system which involves the planets moving and migrating inward and outward during the formation process. But why didn’t the inner planets, including Earth, move in closer, too?

“We don’t know why this didn’t happen in our solar system,” Ragozzine said, but added that KOI-500 will “become a touchstone for future theories that will attempt to describe how compact planetary systems form. Learning about these systems will inspire a new generation of theories to explain why our solar system turned out so differently.”

A few notes of interest about KOI-500:

The five planets have “years” that are only 1.0, 3.1, 4.6, 7.1, and 9.5 days.

“All five planets zip around their star within a region 150 times smaller in area than the Earth’s orbit, despite containing more material than several Earths (the planets range from 1.3 to 2.6 times the size of the Earth). At this rate, you could easily pack in 10 more planets, and they would still all fit comfortably inside the Earth’s orbit,” Ragozzine noted. KOI-500 is approximately 1,100 light-years away in the constellation Lyra, the harp.

Four of the planets orbiting KOI-500 follow synchronized orbits around their host star in a completely unique way — no other known system contains a similar configuration. Work by Ragozzine and his colleagues suggests that planetary migration helped to synchronize the planets.

“KOI” stands for Kepler Object of Interest, and Ragozzine’s findings on this system have not yet been published, and so the system has yet to officially be considered a confirmed planetary system. “Every time we find something like this we give it a license-plate-like number starting with KOI,” Ragozzine said.

When does a KOI become an official planet? Ragozzine said the process is by confirming and validating the data. “Basically you need to prove statistically or by getting a specific measurement that it is not some other astronomical signal,” he said.

This infographic from Space.com supplies more visual details:

Sources: AAS, University of Florida