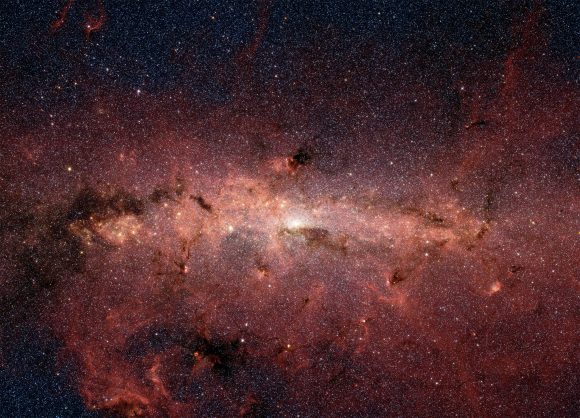

During the 1970s, scientists confirmed that radio emissions coming from the center of our galaxy were due to the presence of a Supermassive Black Hole (SMBH). Located about 26,000 light-years from Earth between the Sagittarius and Scorpius constellation, this feature came to be known as Sagittarius A*. Since that time, astronomers have come to understand that most massive galaxies have an SMBH at their center.

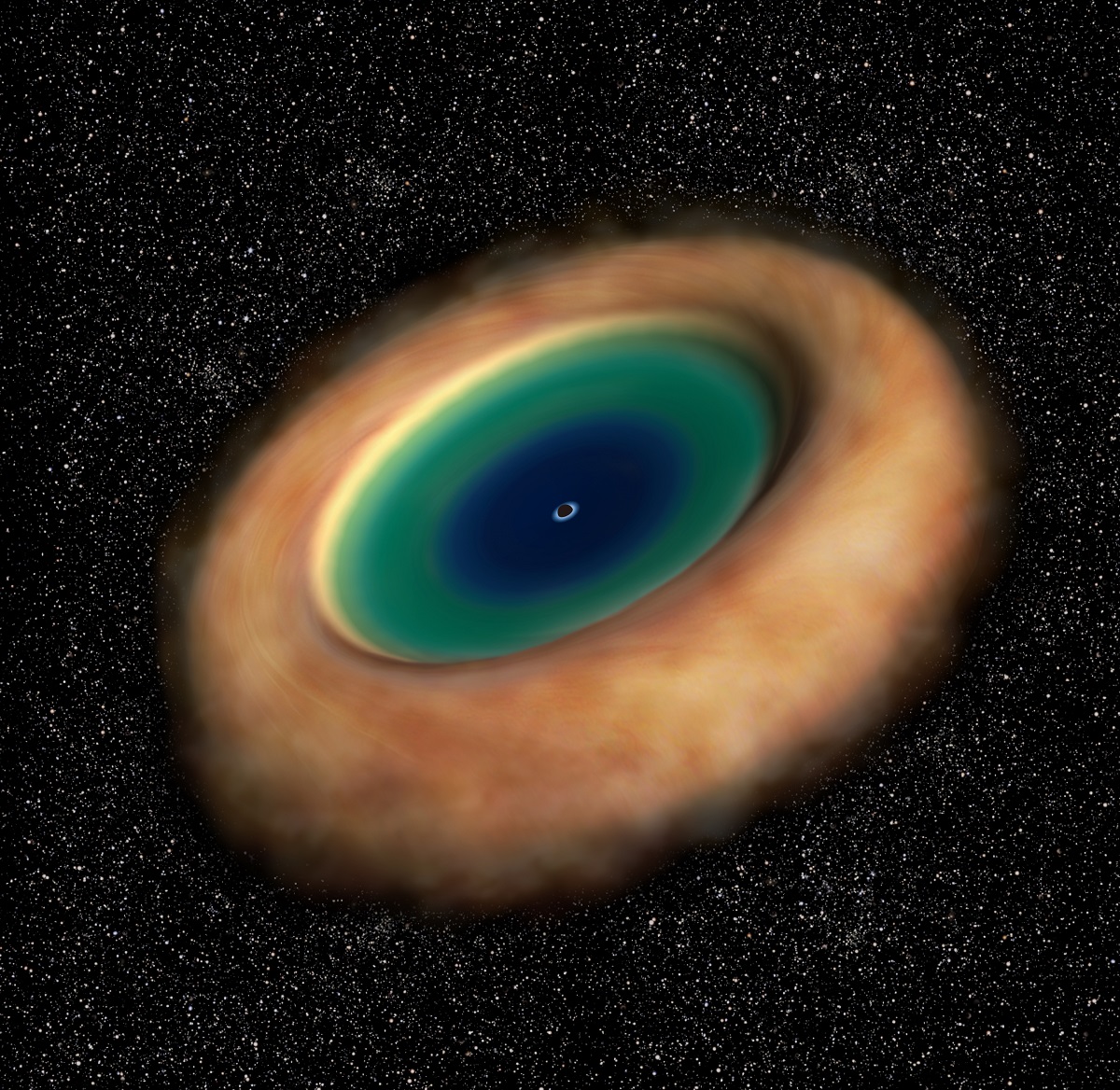

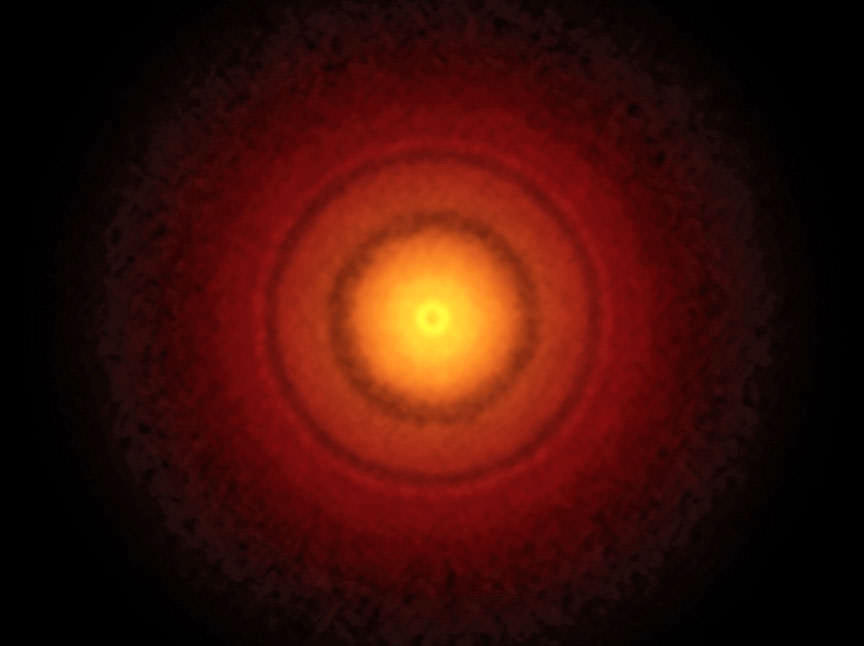

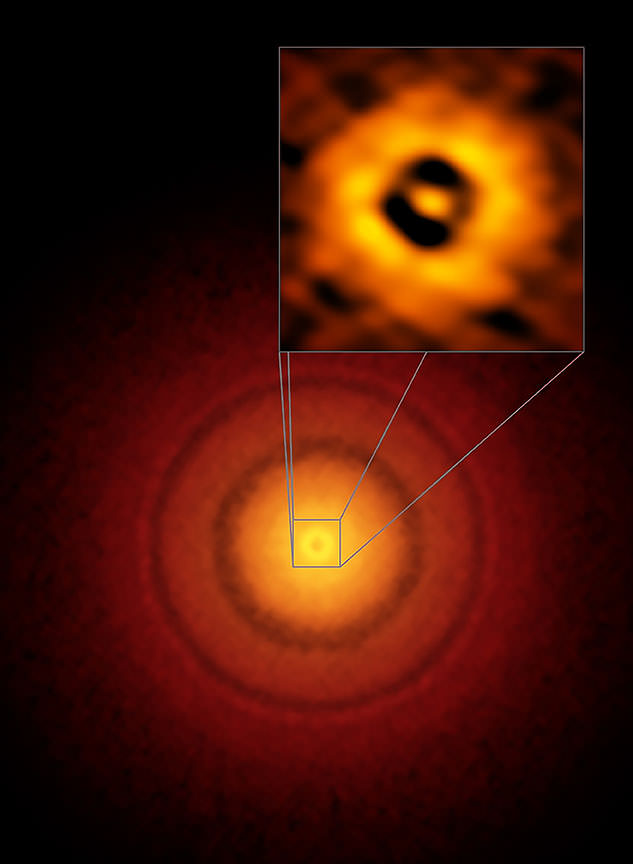

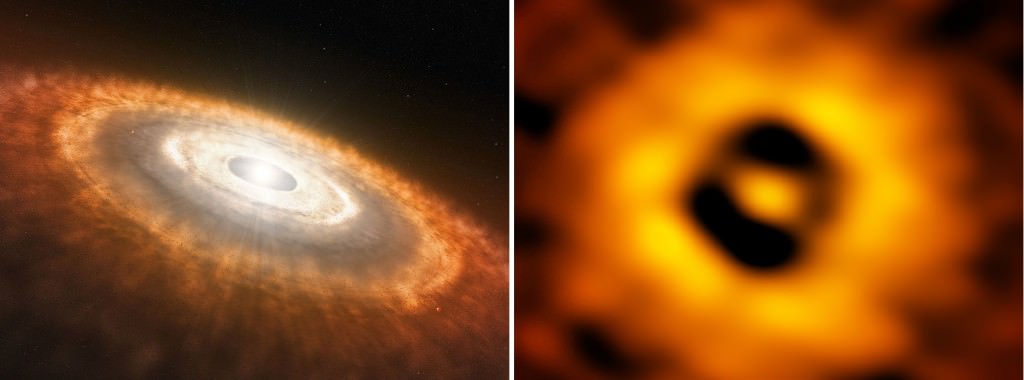

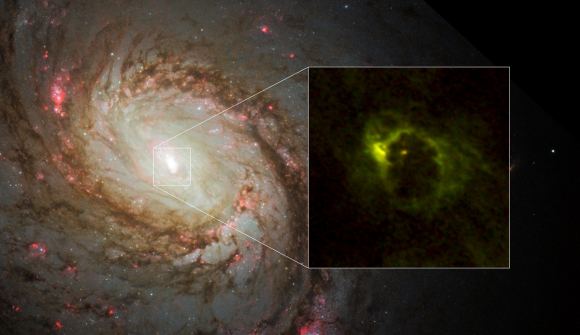

What’s more, astronomers have come to learn that black holes in these galaxies are surrounded by massive rotating toruses of dust and gas, which is what accounts for the energy they put out. However, it was only recently that a team of astronomers, using the the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), were able to capture an image of the rotating dusty gas torus around the supermassive black hole of M77.

The study which details their findings recently appeared in the Astronomical Journal Letters under the title “ALMA Reveals an Inhomogeneous Compact Rotating Dense Molecular Torus at the NGC 1068 Nucleus“. The study was conducted by a team of Japanese researchers from the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan – led by Masatoshi Imanishi – with assistance from Kagoshima University.

Like most massive galaxies, M77 has an Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN), where dust and gas are being accreted onto its SMBH, leading to higher-than-normal luminosity. For some time, astronomers have puzzled over the curious relationship that exists between SMBHs and galaxies. Whereas more massive galaxies have larger SMBHs, host galaxies are still 10 billion times larger than their central black hole.

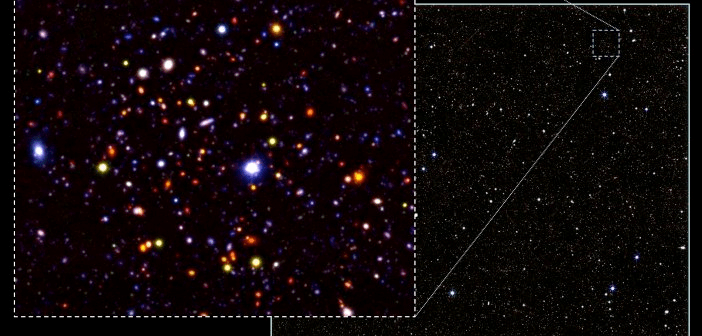

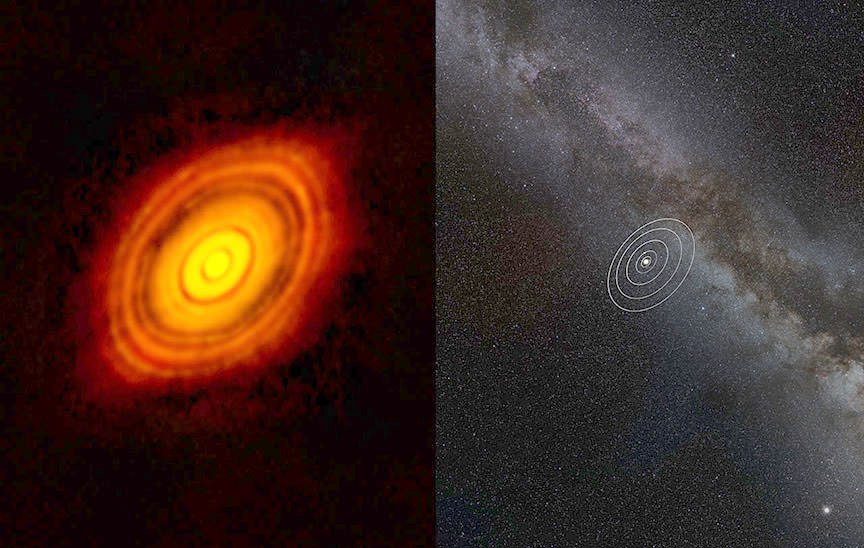

This naturally raises questions about how two objects of vastly different scales could directly affect each other. As a result, astronomers have sought to study AGN is order to determine how galaxies and black holes co-evolve. For the sake of their study, the team conducted high-resolution observations of the central region of M77, a barred spiral galaxy located about 47 million light years from Earth.

Using ALMA, the team imaged the area around M77’s center and were able to resolve a compact gaseous structure with a radius of 20 light-years. As expected, the team found that the compact structure was rotating around the galaxies central black hole. As Masatoshi Imanishi explained in an ALMA press release:

“To interpret various observational features of AGNs, astronomers have assumed rotating donut-like structures of dusty gas around active supermassive black holes. This is called the ‘unified model’ of AGN. However, the dusty gaseous donut is very tiny in appearance. With the high resolution of ALMA, now we can directly see the structure.”

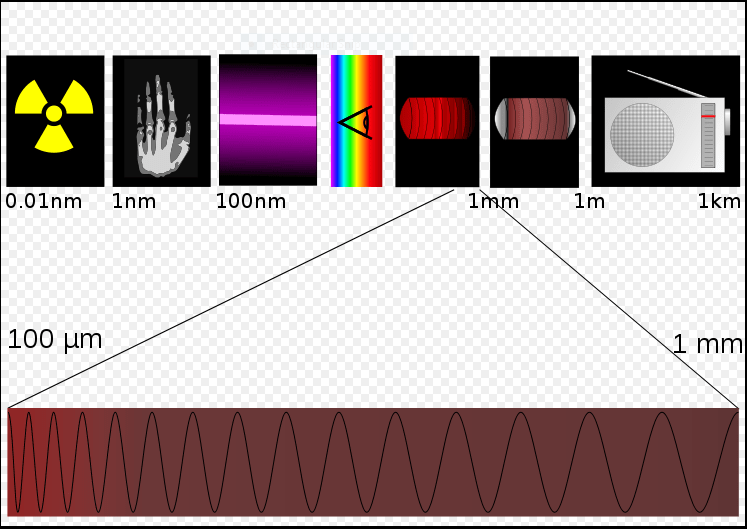

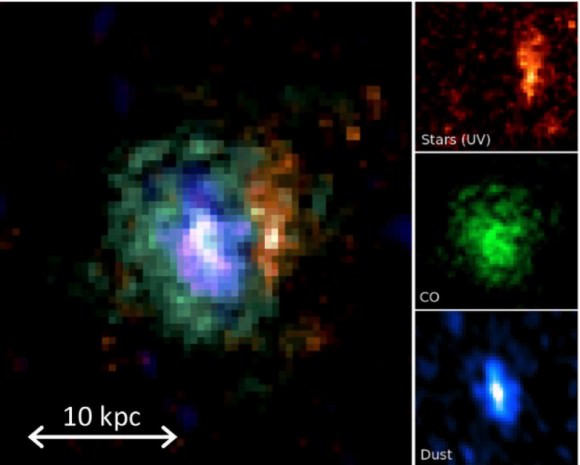

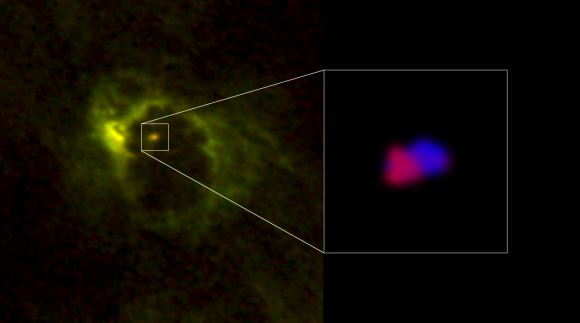

In the past, astronomers have observed the center of M77, but no one has been able to resolve the rotating torus at its center until now. This was made possible thanks to the superior resolution of ALMA, as well as the selection of molecular emissions lines. These emissions lines include hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and formyl ions (HCO+), which emit microwaves only in dense gas, and carbon monoxide – which emits microwaves under a variety of conditions.

The observations of these emission lines confirmed another prediction made by the team, which was that the torus would be very dense. “Previous observations have revealed the east-west elongation of the dusty gaseous torus,” said Imanishi. “The dynamics revealed from our ALMA data agrees exactly with the expected rotational orientation of the torus.”

However, their observations also indicated that the distribution of gas around an SMBH is more complicated that what a simple unified model suggests. According to this model, the rotation of the torus would follow the gravity of the black hole; but what Imanishi and his team found indicated that gas and dust in the torus also exhibit signs of highly random motion.

These could be an indication that the AGN at the center of M77 had a violent history, which could include merging with a small galaxy in the past. In short, the team’s observations indicate that galactic mergers may have a significant impact on how AGNs form and behave. In this respect, their observations of M77s torus are already providing clues as to the galaxy’s history and evolution.

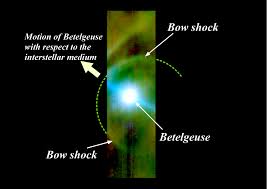

The study of SMBHs, while intensive, is also very challenging. On the one hand, the closest SMBH (Sagittarius A*) is relatively quiet, with only a small amount of gas accreting onto it. At the same time, it is located at the center of our galaxy, where it is obscured by intervening dust, gas and stars. As such, astronomers are forced to look to other galaxies to study how SMBHs and their galaxies co-exist.

And thanks to decades of study and improvements in instrumentation, scientists are beginning to get a clear glimpse of these mysterious regions for the first time. By being able to study them in detail, astronomers are also gaining valuable insight into how such massive black holes and their ringed structures could coexist with their galaxies over time.