[/caption]

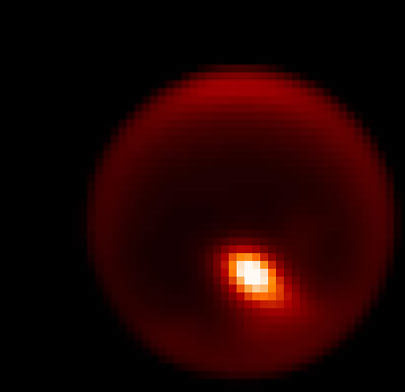

The discovery of dark energy, a mysterious force that is accelerating the expansion of the universe, was based on observations of type 1a supernovae, and these stellar explosions have long been used as “standard candles” for measuring the expansion. But not all type 1A supernovae are created equal. A new study reveals sources of variability in these supernovae, and to accurately probe the nature of dark energy and determine if it is constant or variable over time, scientists will have to find a way to measure cosmic distances with much greater precision than they have in the past.

“As we begin the next generation of cosmology experiments, we will want to use type 1a supernovae as very sensitive measures of distance,” said lead author Daniel Kasen, of a study published in Nature this week. “We know they are not all the same brightness, and we have ways of correcting for that, but we need to know if there are systematic differences that would bias the distance measurements. So this study explored what causes those differences in brightness.”

Kasen and his coauthors–Fritz Röpke of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Garching, Germany, and Stan Woosley, professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz–used supercomputers to run dozens of simulations of type 1a supernovae. The results indicate that much of the diversity observed in these supernovae is due to the chaotic nature of the processes involved and the resulting asymmetry of the explosions.

For the most part, this variability would not produce systematic errors in measurement studies as long as researchers use large numbers of observations and apply the standard corrections, Kasen said. The study did find a small but potentially worrisome effect that could result from systematic differences in the chemical compositions of stars at different times in the history of the universe. But researchers can use the computer models to further characterize this effect and develop corrections for it.

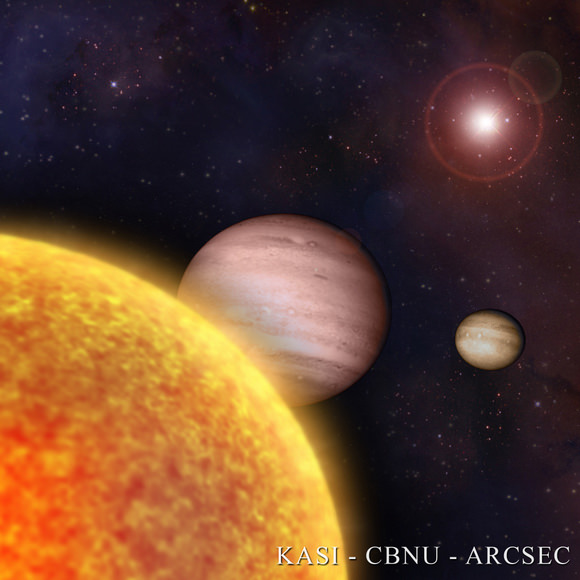

A type 1a supernova occurs when a white dwarf star acquires additional mass by siphoning matter away from a companion star. When it reaches a critical mass–1.4 times the mass of the Sun, packed into an object the size of the Earth–the heat and pressure in the center of the star spark a runaway nuclear fusion reaction, and the white dwarf explodes. Since the initial conditions are about the same in all cases, these supernovae tend to have the same luminosity, and their “light curves” (how the luminosity changes over time) are predictable.

Some are intrinsically brighter than others, but these flare and fade more slowly, and this correlation between the brightness and the width of the light curve allows astronomers to apply a correction to standardize their observations. So astronomers can measure the light curve of a type 1a supernova, calculate its intrinsic brightness, and then determine how far away it is, since the apparent brightness diminishes with distance (just as a candle appears dimmer at a distance than it does up close).

The computer models used to simulate these supernovae in the new study are based on current theoretical understanding of how and where the ignition process begins inside the white dwarf and where it makes the transition from slow-burning combustion to explosive detonation.

The simulations showed that the asymmetry of the explosions is a key factor determining the brightness of type 1a supernovae. “The reason these supernovae are not all the same brightness is closely tied to this breaking of spherical symmetry,” Kasen said.

The dominant source of variability is the synthesis of new elements during the explosions, which is sensitive to differences in the geometry of the first sparks that ignite a thermonuclear runaway in the simmering core of the white dwarf. Nickel-56 is especially important, because the radioactive decay of this unstable isotope creates the afterglow that astronomers are able to observe for months or even years after the explosion.

“The decay of nickel-56 is what powers the light curve. The explosion is over in a matter of seconds, so what we see is the result of how the nickel heats the debris and how the debris radiates light,” Kasen said.

Kasen developed the computer code to simulate this radiative transfer process, using output from the simulated explosions to produce visualizations that can be compared directly to astronomical observations of supernovae.

The good news is that the variability seen in the computer models agrees with observations of type 1a supernovae. “Most importantly, the width and peak luminosity of the light curve are correlated in a way that agrees with what observers have found. So the models are consistent with the observations on which the discovery of dark energy was based,” Woosley said.

Another source of variability is that these asymmetric explosions look different when viewed at different angles. This can account for differences in brightness of as much as 20 percent, Kasen said, but the effect is random and creates scatter in the measurements that can be statistically reduced by observing large numbers of supernovae.

The potential for systematic bias comes primarily from variation in the initial chemical composition of the white dwarf star. Heavier elements are synthesized during supernova explosions, and debris from those explosions is incorporated into new stars. As a result, stars formed recently are likely to contain more heavy elements (higher “metallicity,” in astronomers’ terminology) than stars formed in the distant past.

“That’s the kind of thing we expect to evolve over time, so if you look at distant stars corresponding to much earlier times in the history of the universe, they would tend to have lower metallicity,” Kasen said. “When we calculated the effect of this in our models, we found that the resulting errors in distance measurements would be on the order of 2 percent or less.”

Further studies using computer simulations will enable researchers to characterize the effects of such variations in more detail and limit their impact on future dark-energy experiments, which might require a level of precision that would make errors of 2 percent unacceptable.

Source: EurekAlert