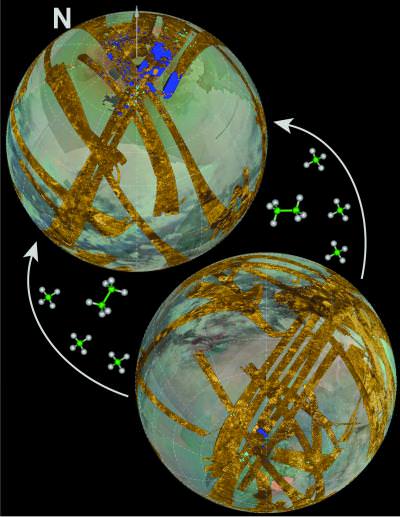

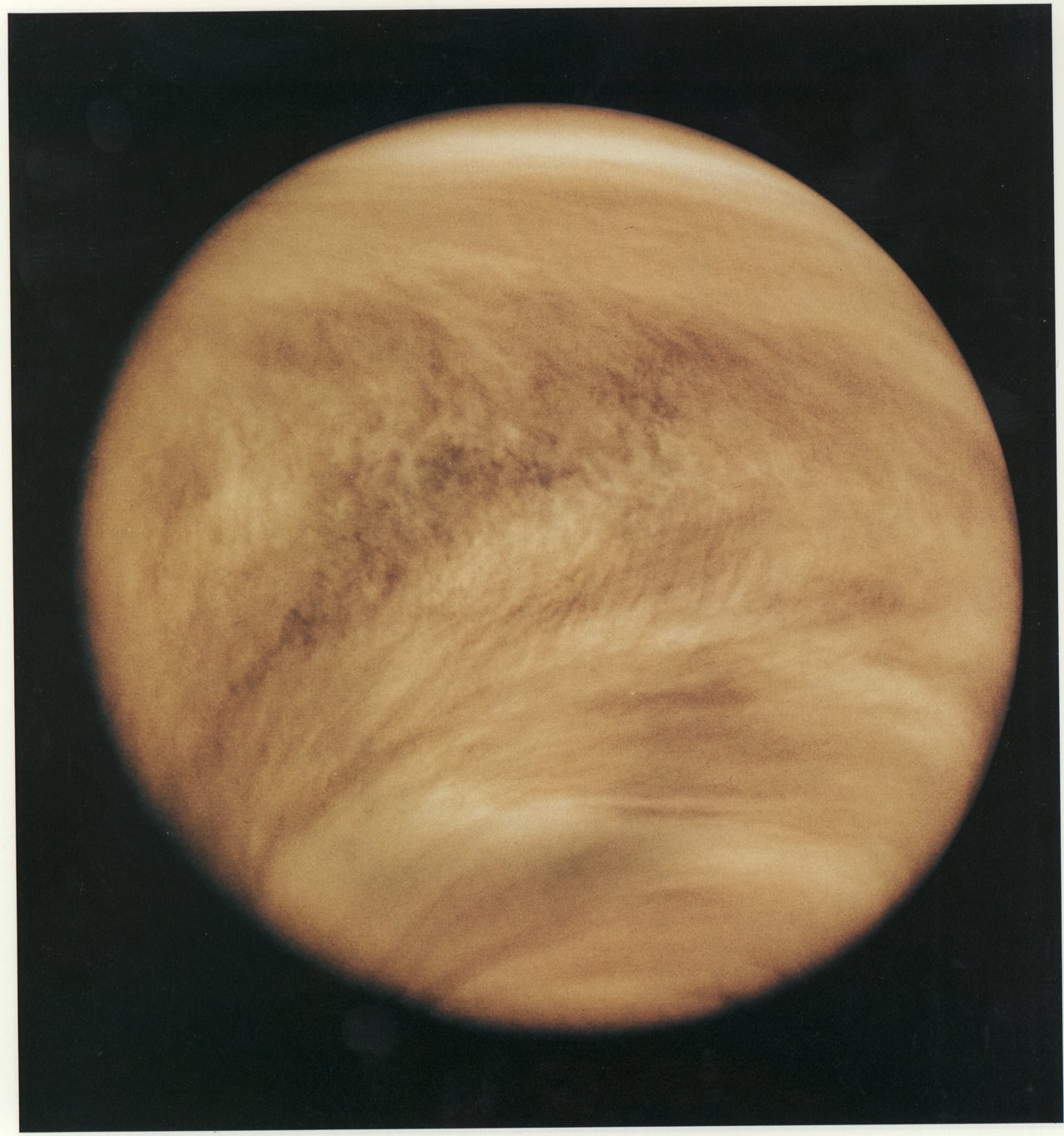

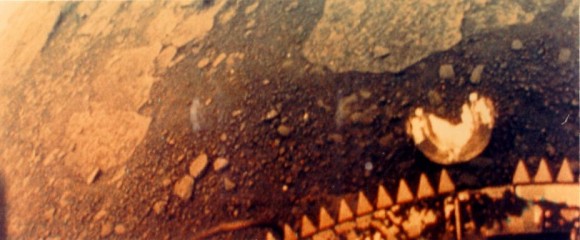

If you’ve wanted to take a swim in a lake on Titan, don’t: they’re not lakes like we have here on Earth, composed of methane and ethane instead of water. If you have somehow evolved lungs to breathe and swim in these chemicals, you should take your beach vacation in the northern hemisphere of Titan, where you’ll find many more lakes. Data taken by the Cassini mission has shown that there are more of these methane lakes concentrated in the northern hemisphere of Saturn’s moon than in the southern hemisphere. A recent analysis of the Cassini findings by a team at Caltech has shown that the cause of this asymmetry of lakes is due to the orbit of Saturn.

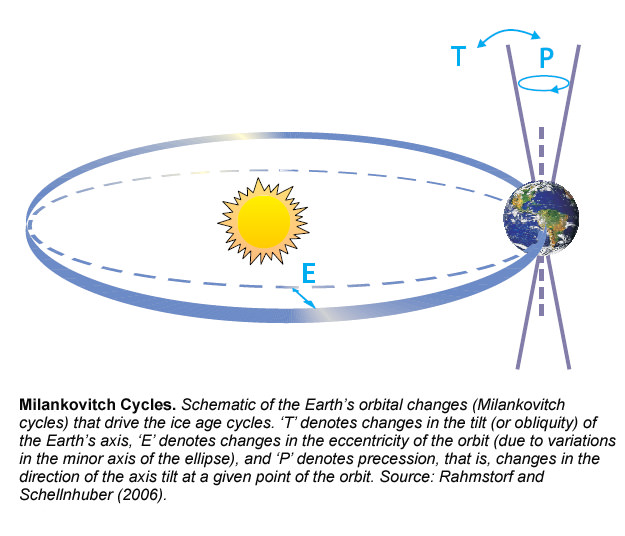

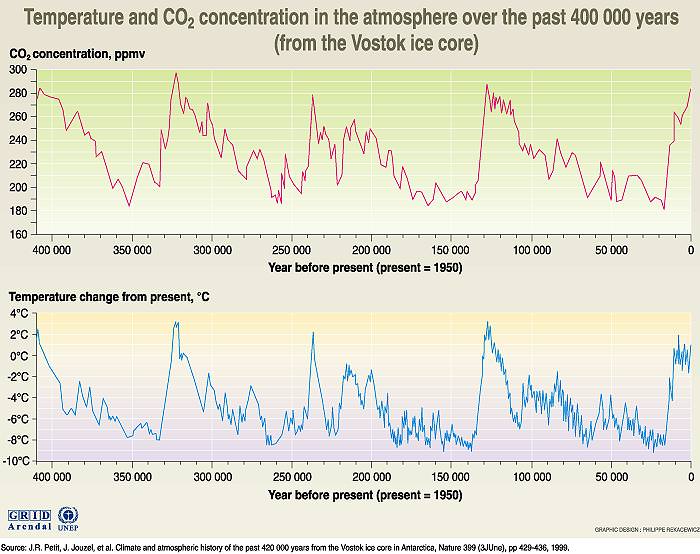

Because of the eccentricity of Saturn’s orbit around the Sun, there is a constant transfer of methane in Titan’s atmosphere from the south to the north. This effect is called astronomical climate forcing, or the Milankovitch cycle, and is thought to be the cause of ice ages here on Earth. We wrote about the Milankovitch cycles and their influence on climate change just earlier today.

Scientists originally thought that the northern hemisphere was somehow differently structured than the south. Imaging data from Cassini showed that ethane and methane lakes cover 20 times more area in the northern hemisphere than lakes in the south. There also are more half-filled and dried-up lake beds in the north. For example, if the composition of the surface of Titan somehow allowed for more methane and ethane to permeate the ground more in the north, this could have explained the difference. But further data from Cassini has confirmed that there is no great difference in topography between the two hemispheres of Titan.

The seasonal differences on Titan only partially explain the asymmetry of lake formation. One year on Titan is 29.5 Earth years, so about every 15 years the seasons of Titan reverse. In other words, the winter and summer seasons could have caused the evaporation and transfer of gas to the north, where it is cooled and is currently in the form of lakes until the seasons change again.

A team led by Oded Aharonson, associate professor of planetary science at Caltech found that there was much more to the story, though. The seasonal effect could only account for changes in lake depth for each hemisphere to vary by about one meter. Titan’s lakes are hundreds of meters deep on average, and this process is too slow to explain the depth changes we see today. It became apparent that the seasonal differences were only partly contributing to this difference.

“On Titan, there are long-term climate cycles in the global movement of methane that make lakes and carve lake basins. In both cases we find a record of the process embedded in the geology,” Aharonson said in a press release.

The Milankovitch cycle on Titan is likely the cause of the lake imbalance. Summers in the north are long and relatively mild, while those in the south are shorter, but warmer. Over thousands of years, this leads to a net movement of gas towards the north, which then condenses and stays there in liquid form. During southern summer Titan is close to the sun, and during northern summer it is approximately 12% further from the Sun.

Their results appear in the advance online version of Nature Geoscience for November 29th. Animations detailing the transfer are available on Oded Aharonson’s home page.

If Cassini would have been sent to Titan 32,000 years ago, the picture would have been reversed: the south pole would have many more lakes than the north. Conversely, any Titanian deep-lake divers in a few thousand years will fare much better in the lakes of the south.

Source: Eurekalert, Oded Aharonson’s Home Page

So you might want to rethink that next coastal real estate purchase – or hope for the best from

So you might want to rethink that next coastal real estate purchase – or hope for the best from