Eclipse season is upon us this week with the first eclipse of 2013, a brief partial lunar eclipse.

The lunar eclipse on April 25, 2013 is a shallow one, meaning only a paltry 1.47% of the lunar limb will be immersed in the dark umbra or inner shadow of the Earth. Observers can expect to see only a dark diffuse edge of the inner shadow nick the the Moon as is grazes the umbra.

A partial lunar eclipse this shallow hasn’t occurred since May 3rd, 1958 (0.9%) and won’t be topped until September 28th, 2034 (1.4%). This is the second slightest partial lunar eclipse for this century.

Another term for this sort of alignment is known as a syzygy, a great triple-letter word score in Scrabble!

A video simulation of the eclipse:

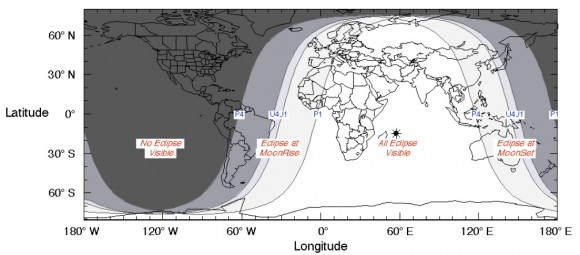

The eclipse will be visible in its entirety from eastern Europe & Africa across the Middle East eastward to southeast Asia and western Australia. The eclipse will be visible at moonrise from South America to Western Europe and occurring at moonset for eastern Australia and the Far East. The partially eclipsed Moon will be directly overhead just off the northeastern coast of Madagascar. The eclipse will not be visible from North America.

Two eclipse seasons occur each year when the nodal points of the Moon’s orbit intersect the ecliptic while aligned with the position of the Sun and the Earth’s shadow. The Moon’s orbit is inclined 5.15° degrees with respect to the ecliptic, which traces out our own planet’s path around the Sun. If this intersection occurs near New or Full Moon, a solar or lunar eclipse occurs.

If the Moon’s orbit was not inclined to our own, we’d get two eclipses per lunation, one solar and one lunar.

2013 has 5 eclipses, 3 lunar and 2 annular. The minimum number of eclipses that can occur in a calendar year is 4, and the maximum is 7, as will next occur in 2038.

The 3 lunar eclipses in 2013 are this week’s partial eclipse on April 25th and two faint penumbral eclipses, one on May 25th and another on October 18th. There is no total lunar eclipse in 2013. The last one occurred on December 10th 2011, and the next one won’t occur until April 15th 2014, favoring the Pacific Rim region.

This eclipse will also set us up for the first solar eclipse of 2013, an annular eclipse crossing NE Australia (in fact crossing the path of last year’s total eclipse near Cairns) and the south Pacific on May 10th. The only solar totality that will touch the surface of the Earth in 2013 is the hybrid eclipse on November 3rd spanning Africa and the South Atlantic with a maximum totality of 1 minute & 40 seconds.

Contact times for the April 25 shallow eclipse:

P1-The Moon touches the penumbra-18:03:41 UT

U1-The Moon touches the umbra-19:54:04 UT

Mid-Eclipse-20:08:37.5 UT

U4 -The Moon quits the umbra-20:21:04 UT

P4-The Moon quits the penumbra- 22:11:23 UT

The length of the partial phase of the eclipse is exactly 27 minutes, and the length of the entire eclipse is 4 hours, 7 minutes and 42 seconds.

This particular eclipse is part of saros series 112 and is member 65 of 72.

This saros cycle began in 859 C.E. on May 20th and will end in 2139 on July 12th with a penumbral lunar eclipse. One famous member of this series was 52. This eclipse was one of many used by Captain James Cook to fix his longitude at sea on December 4th 1778. Christopher Columbus also attempted this feat while voyaging to the New World. It’s a fun project that anyone can try!

I also remember watching the last eclipse in this series from South Korea on April 15th 1995, a slightly better partial of 11.14%.

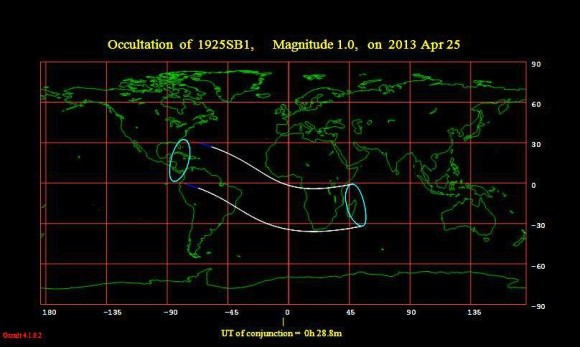

An occultation of the bright star Spica occurs just 20 hours prior as seen from South Africa across the southern Atlantic. This the 5th in a series of 13 occultations of the star by the Moon in 2013.

The +2.8th magnitude star Zubenelgenubi (Alpha Librae) is occulted by the waning gibbous Moon just 15 hours after the eclipse for Australia and the South Pacific.

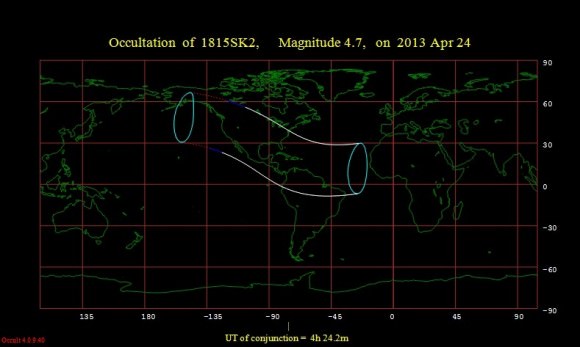

Another occultation of a bright star with potential this week is +4.7th magnitude Chi Virginis across North America on the morning of Wednesday, April 24th centered on 4:24 UT.

Also keep an eye out for +0.1 magnitude Saturn near the Full Moon. Saturn reaches opposition this weekend for 2013 on April 28th

Full Moon occurs near mid-eclipse at 20:00 UT/16:00 EDT on April 25th. Colloquial names for the April Full Moon are the Pink, Fish, Sprouting Grass, Egg, Seed, & Waking Moon.

Sure, the penumbral phases of an eclipse are subtle and may not be noticeable to the naked eye… but it is possible to see the difference photographically. Simply take a photo of the Moon before it enters the Earth’s penumbra, then take one during the penumbral phase and then another one after. Be sure to keep the ISO/f-stop and shutter speed exactly the same throughout. Also, this project only works if the eclipsed Moon is high in the sky throughout the exposures, as the thick air low to the horizon will discolor the Moon as well. Compare the shots; do you see a difference?

A penumbral eclipse would offer a good proof of concept test for hunting for transiting exoplanets as well, although to our knowledge, no one has ever attempted this.

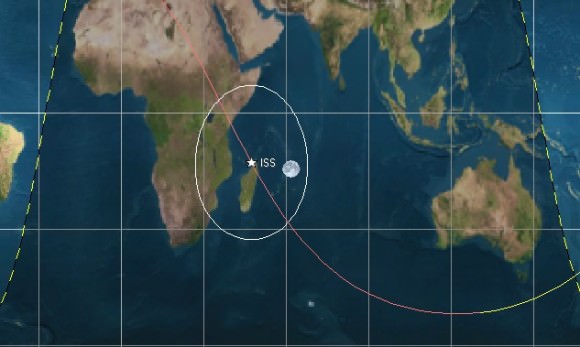

Finally, calling out to all Universe Today readers in Madagascar. YOU may just be able to catch a transit of the International Space Station in front of the Moon just as the ragged edge of the umbra becomes apparent on the limb of the Moon. Check CALSky a day or so prior to the eclipse for a refined path… it would be an unforgettable pic!

And if any ambitious observer is planning to live stream the eclipse, let us know and we’ll add your embed to this post. We do not expect an avalanche of web broadcasts, but hey, we’d definitely honor the effort! Slooh is usually a pretty dependable site for live eclipse broadcasts, and as of this writing seems to have broadcast scheduled in the cue.

Happy eclipse-spotting!