[/caption]

From an NRAO press release:

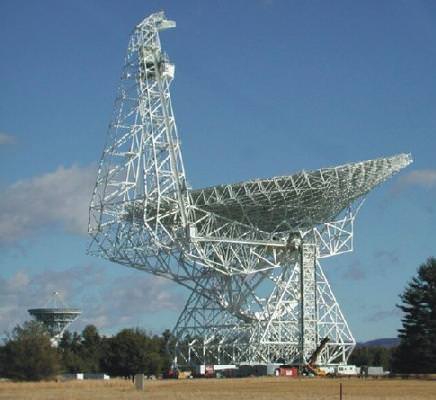

Dark energy is the label scientists have given to what is causing the Universe to expand at an accelerating rate, and is believed to make up nearly three-fourths of the mass and energy of the Universe. While the acceleration was discovered in 1998, its cause remains unknown. Physicists have advanced competing theories to explain the acceleration, and believe the best way to test those theories is to precisely measure large-scale cosmic structures. A new technique developed for the Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope (GBT) have given astronomers a new way to map large cosmic structures such as dark energy.

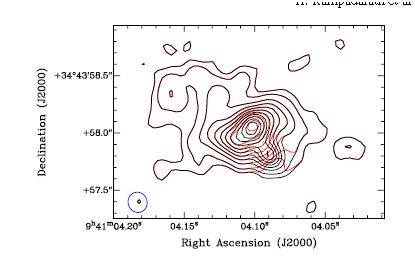

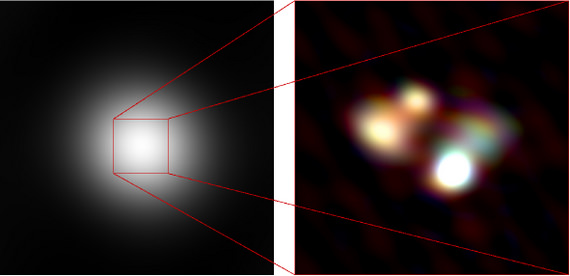

Sound waves in the matter-energy soup of the extremely early Universe are thought to have left detectable imprints on the large-scale distribution of galaxies in the Universe. The researchers developed a way to measure such imprints by observing the radio emission of hydrogen gas. Their technique, called intensity mapping, when applied to greater areas of the Universe, could reveal how such large-scale structure has changed over the last few billion years, giving insight into which theory of dark energy is the most accurate.

“Our project mapped hydrogen gas to greater cosmic distances than ever before, and shows that the techniques we developed can be used to map huge volumes of the Universe in three dimensions and to test the competing theories of dark energy,” said Tzu-Ching Chang, of the Academia Sinica in Taiwan and the University of Toronto.

To get their results, the researchers used the GBT to study a region of sky that previously had been surveyed in detail in visible light by the Keck II telescope in Hawaii. This optical survey used spectroscopy to map the locations of thousands of galaxies in three dimensions. With the GBT, instead of looking for hydrogen gas in these individual, distant galaxies — a daunting challenge beyond the technical capabilities of current instruments — the team used their intensity-mapping technique to accumulate the radio waves emitted by the hydrogen gas in large volumes of space including many galaxies.

“Since the early part of the 20th Century, astronomers have traced the expansion of the Universe by observing galaxies. Our new technique allows us to skip the galaxy-detection step and gather radio emissions from a thousand galaxies at a time, as well as all the dimly-glowing material between them,” said Jeffrey Peterson, of Carnegie Mellon University.

The astronomers also developed new techniques that removed both man-made radio interference and radio emission caused by more-nearby astronomical sources, leaving only the extremely faint radio waves coming from the very distant hydrogen gas. The result was a map of part of the “cosmic web” that correlated neatly with the structure shown by the earlier optical study. The team first proposed their intensity-mapping technique in 2008, and their GBT observations were the first test of the idea.

“These observations detected more hydrogen gas than all the previously-detected hydrogen in the Universe, and at distances ten times farther than any radio wave-emitting hydrogen seen before,” said Ue-Li Pen of the University of Toronto.

“This is a demonstration of an important technique that has great promise for future studies of the evolution of large-scale structure in the Universe,” said National Radio Astronomy Observatory Chief Scientist Chris Carilli, who was not part of the research team.

In addition to Chang, Peterson, and Pen, the research team included Kevin Bandura of Carnegie Mellon University. The scientists reported their work in the July 22 issue of the scientific journal Nature.