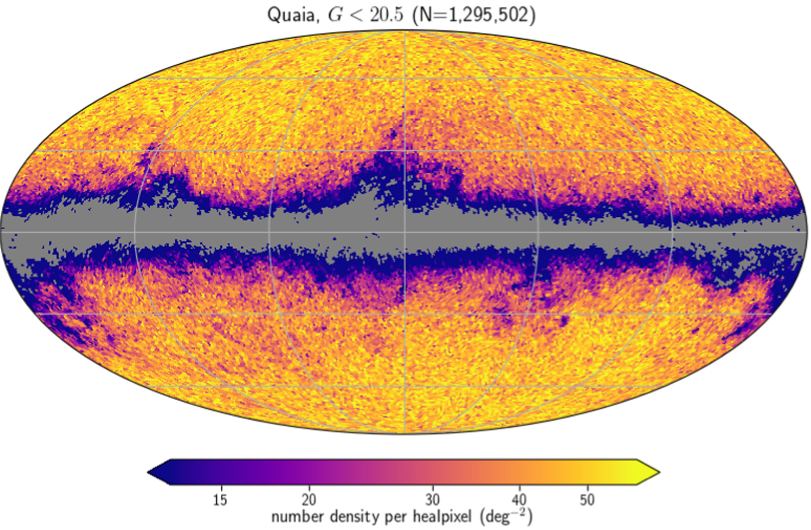

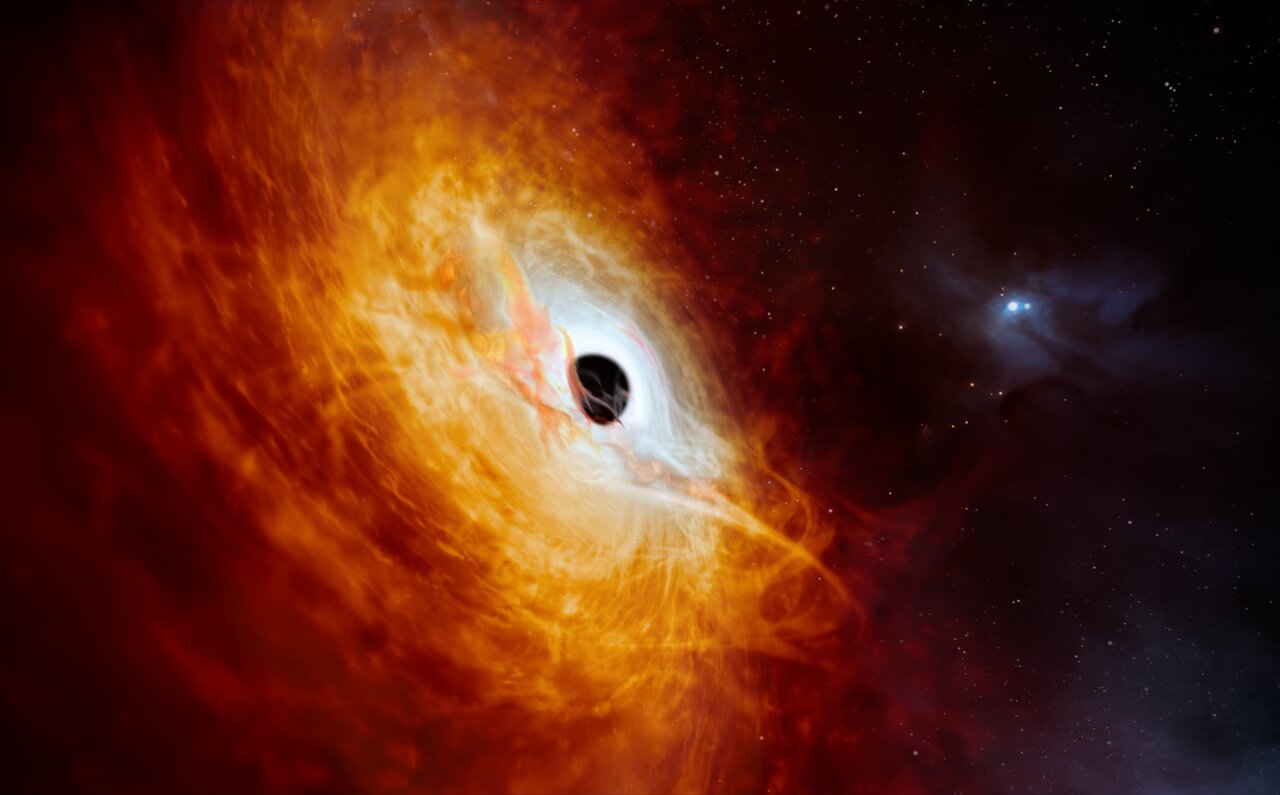

Not long ago, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) peered into Cosmic Dawn, the cosmological period when the first galaxies formed less than one billion years after the Big Bang. In the process, it discovered something rather surprising. Not only were there more galaxies (and brighter ones, too!) than expected, but these galaxies had supermassive black holes (SMBH) much larger than cosmological models predicted. For astronomers and cosmologists, explaining how these galaxies and their SMBHs (aka. quasars) could have grown so large less than a billion years after the Big Bang has become a major challenge.

Several proposals have been made, ranging from optical illusions to Dark Matter accelerating black hole growth. In a recent study, an international team led by researchers from the National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) analyzed a sample of 21 quasars, among the most distant ever discovered. The results suggest that the supermassive black holes at the center of these galaxies may have reached their surprising masses through very rapid accretion, providing a plausible explanation for how galaxies and their SMBHs grew and evolved during the early Universe.

Continue reading “New Research may Explain how Supermassive Black Holes in the Early Universe Grew so Fast”