[/caption]

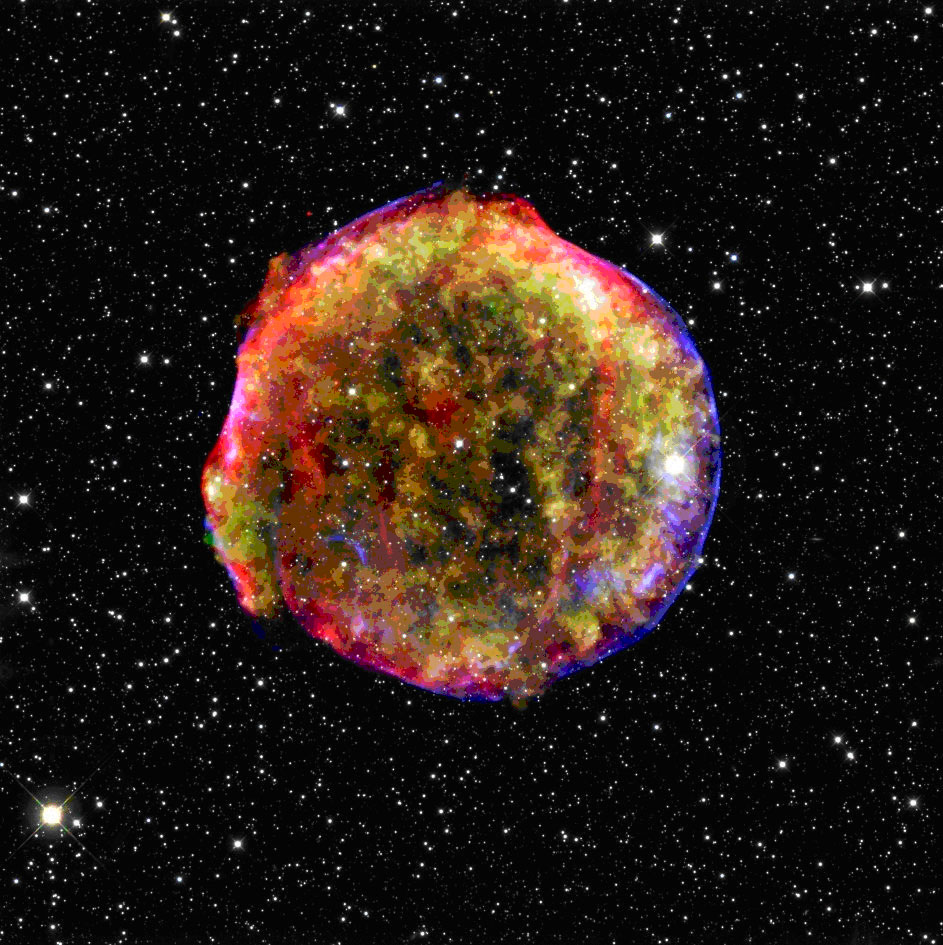

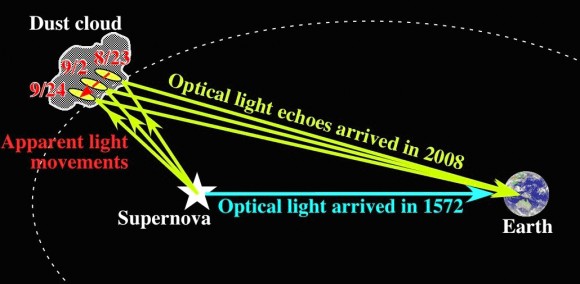

On November 11, 1572 Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe and other skywatchers observed what they thought was a new star. A bright object appeared in the constellation Cassiopeia, outshining even Venus, and it stayed there for several months until it faded from view. What Brahe actually saw was a supernova, a rare event where the violent death of a star sends out an extremely bright outburst of light and energy. The remains of this event can still be seen today as Tycho’s supernova remnant. Recently, a group of astronomers used the Subaru Telescope to attempt a type of time travel by observing the same light that Brahe saw back in the 16th century. They looked at ‘light echoes’ from the event in an effort to learn more about the ancient supernova.

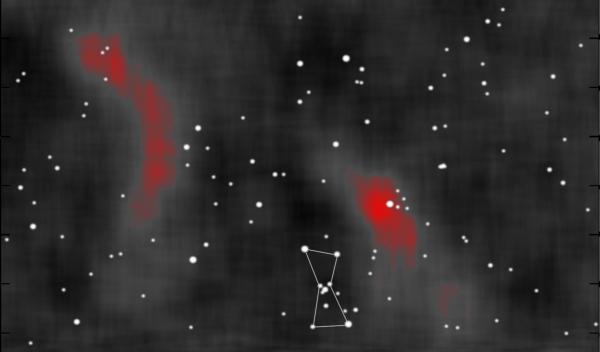

A ‘light echo’ is light from the original supernova event that bounces off dust particles in surrounding interstellar clouds and reaches Earth many years after the direct light passes by; in this case, 436 years ago. This same team used similar methods to uncover the origin of supernova remnant Cassiopeia A in 2007. Lead project astronomer at Subaru, Dr. Tomonori Usuda, said “using light echoes in supernova remnants is time-traveling in a way, in that it allows us to go back hundreds of years to observe the first light from a supernova event. We got to relive a significant historical moment and see it as famed astronomer Tycho Brahe did hundreds of years ago. More importantly, we get to see how a supernova in our own galaxy behaves from its origin.”

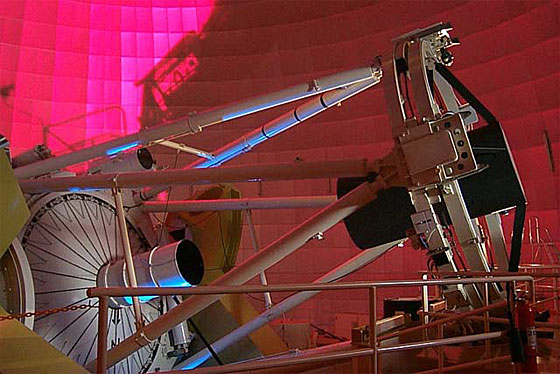

On September 24, 2008, using the Faint Object Camera and Spectrograph (FOCAS) instrument at Subaru, astronomers looked at the signatures of the light echoes to see the spectra that were present when Supernova 1572 exploded. They were able to obtain information about the nature of the original blast, and determine its origin and exact type, and relate that information to what we see from its remnant today. They also studied the explosion mechanism.

What they discovered is that Supernova 1572 was very typical of a Type Ia supernova. In comparing this supernova with other Type Ia supernovae outside our galaxy, they were able to show that Tycho’s supernova belongs to the majority class of Normal Type Ia, and, therefore, is now the first confirmed and precisely classified supernova in our galaxy.

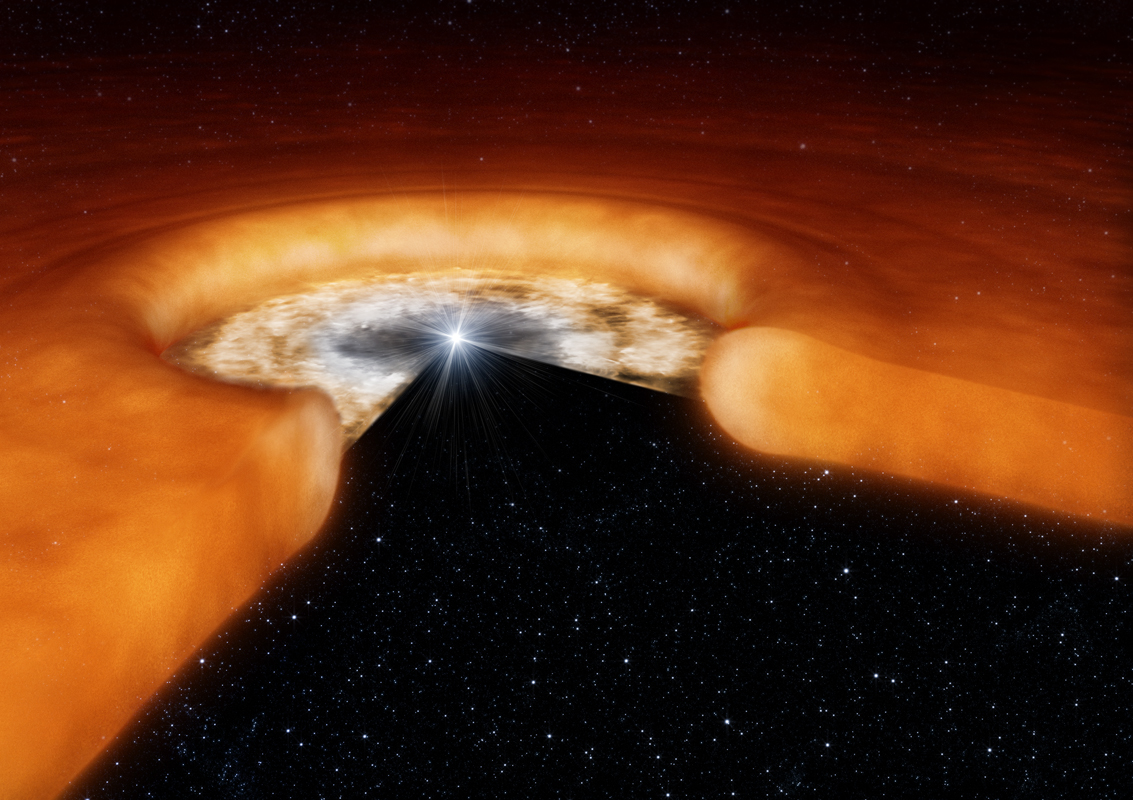

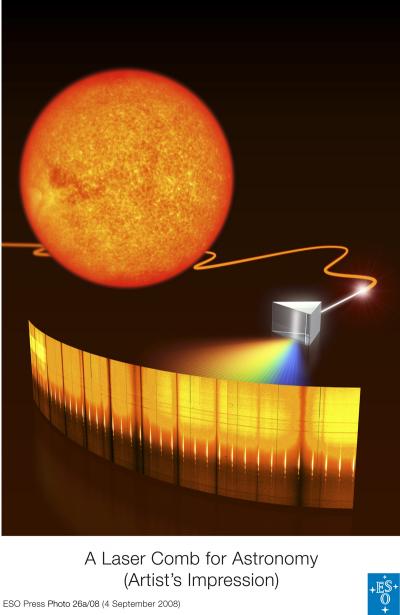

This finding is significant because Type Ia supernovae are the primary source of heavy elements in the Universe, and play an important role as cosmological distance indicators, serving as ‘standard candles’ because the level of the luminosity is always the same for this type of supernova.

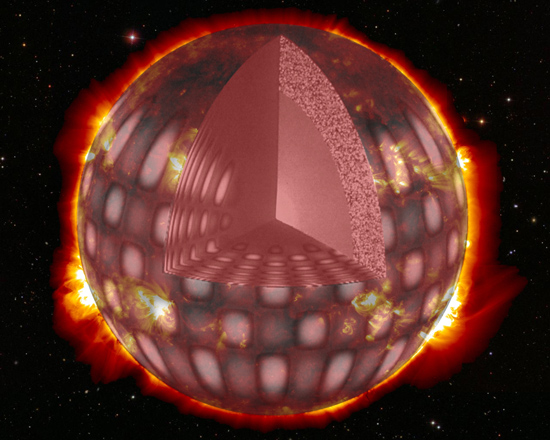

For Type Ia supernovae, a white dwarf star in a close binary system is the typical source, and as the gas of the companion star accumulates onto the white dwarf, the white dwarf is progressively compressed, and eventually sets off a runaway nuclear reaction inside that eventually leads to a cataclysmic supernova outburst. However, as Type Ia supernovae with luminosity brighter/fainter than standard ones have been reported recently, the understanding of the supernova outburst mechanism has come under debate. In order to explain the diversity of the Type Ia supernovae, the Subaru team studied the outburst mechanisms in detail.

This observational study at Subaru established how light echoes can be used in a spectroscopic manner to study supernovae outburst that occurred hundreds of years ago. The light echoes, when observed at different position angles from the source, enabled the team to look at the supernova in a three dimensional view. This study indicated Tycho’s supernova was an aspherical/nonsymmetrical explostion. For the future, this 3D aspect will accelerate the study of the outburst mechanism of supernova based on their spatial structure, which, to date, has been impossible with distant supernovae in galaxies outside the Milky Way.

The results of this study appear in the 4 December 2008 issue of the science journal Nature.

Source: Subaru Telescope