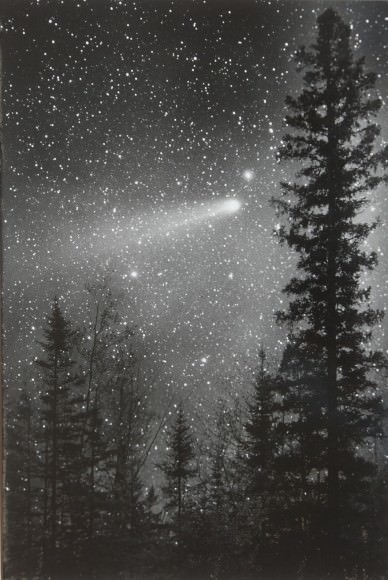

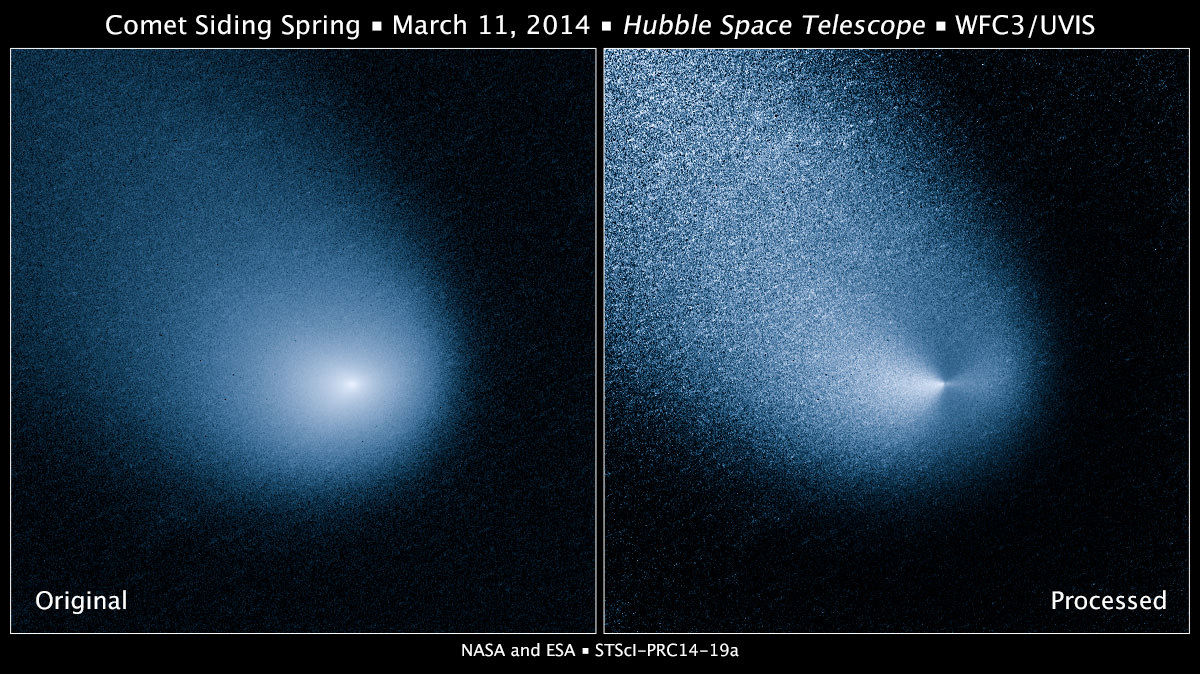

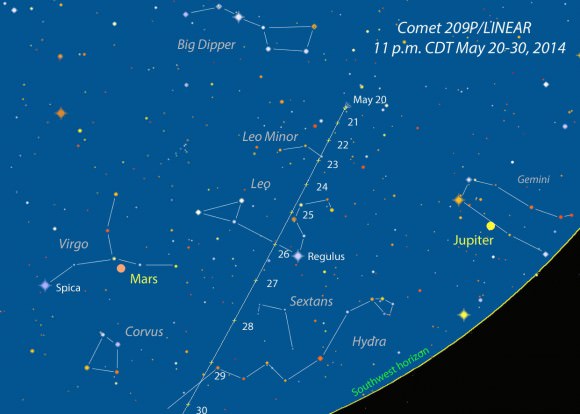

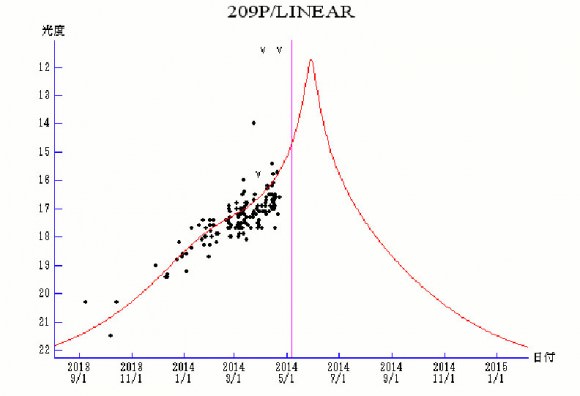

As we anxiously await the arrival of a potentially rich new meteor shower this weekend, its parent comet, 209P/LINEAR, draws ever closer and brighter. Today it shines feebly at around magnitude +13.7 yet possesses a classic form with bright head and tail. It’s rapidly approaching Earth, picking up speed every night and hopefully will be bright enough to see in your telescope very soon.

The comet was discovered in Feb. 2004 by the Lincoln Laboratory Near-Earth Asteroid Research (LINEAR) automated sky survey. Given its stellar appearance at the time of discovery it was first thought to be an asteroid, but photos taken the following month photos by Rob McNaught (Siding Spring Observatory, Australia) revealed a narrow tail. Unlike long period comets Hale-Bopp and the late Comet ISON that swing around the sun once every few thousand years or few million years, this one’s a frequent visitor, dropping by every 5.09 years.

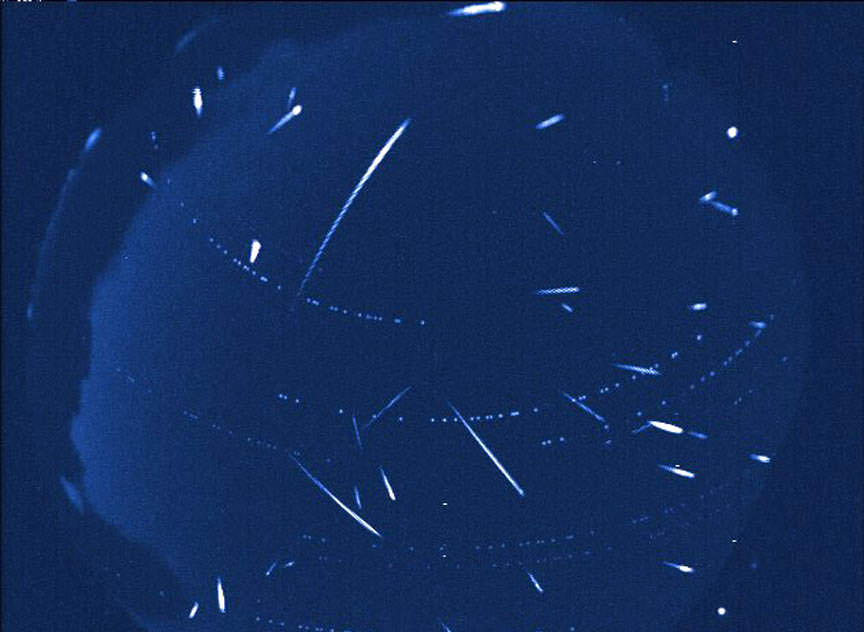

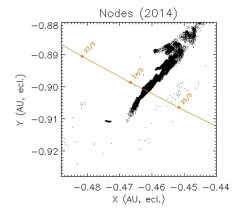

209P/LINEAR belongs to the Jupiter family of comets, a group of comets with periods of less than 20 years whose orbits are controlled by Jupiter. When closest at perihelion, 209P/LINEAR coasts some 90 million miles from the sun; the far end of its orbit crosses that of Jupiter. Comets that ply the gravitational domain of the solar system’s largest planet occasionally get their orbits realigned. In 2012, during a relatively close pass of that planet, Jupiter perturbed 209P’s orbit, bringing the comet and its debris trails to within 280,000 miles (450,000 km) of Earth’s orbit, close enough to spark the meteor shower predicted for this Friday night/Saturday morning May 23-24.

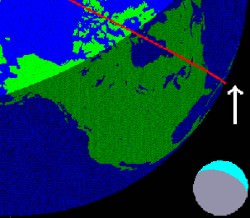

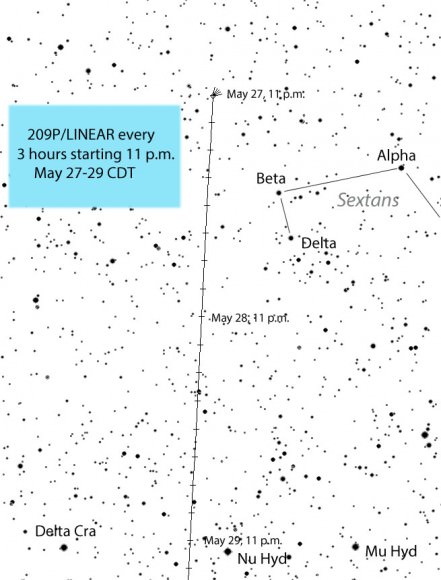

This time around the sun, the comet itself will fly just 5.15 million miles (21 times the distance to the moon) from Earth around 3 a.m. CDT (8 hours UT) May 29 a little more than 3 weeks after perihelion, making it the 9th closest comet encounter ever observed. Given , you’d think 209P would become a bright object, perhaps even visible with the naked eye, but predictions call for it to reach about magnitude +11 at best. That means you’ll need an 8-inch telescope and dark sky to see it well. Either the comet’s very small or producing dust at a declining rate or both. Research published by Quanzhi Ye and Paul A. Wiegert describes the comet’s current dust production as low, a sign that 209P could be transitioning to a dormant comet or asteroid.

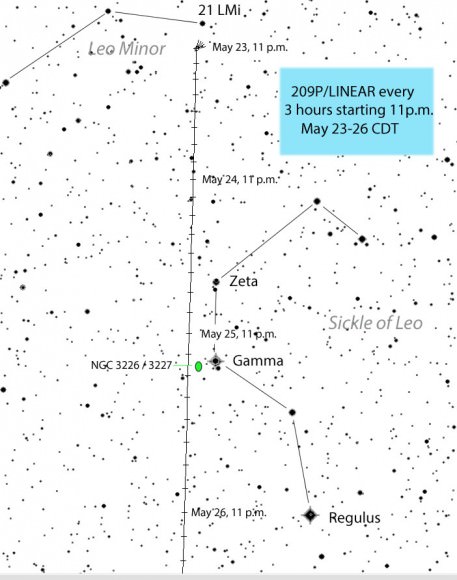

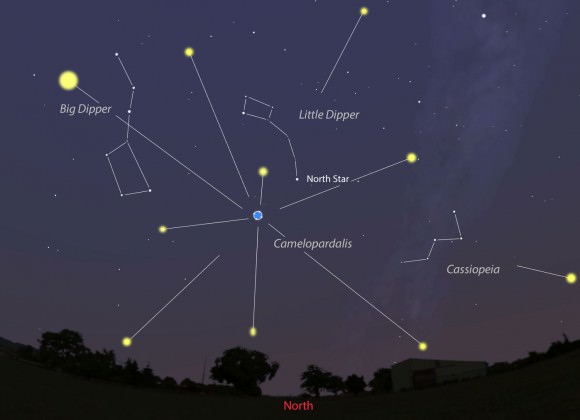

Fortunately, the moon’s out of the way this week and next when 209P/LINEAR is closest and brightest. Since we enjoy comets in part because of their unpredictability, maybe a few surprises will be in the offing including a brighter than expected appearance. The maps will help you track down 209P during the best part of its apparition. I deliberately chose ‘black stars on a white background’ for clarity in use at the telescope. It also saves on printer ink!

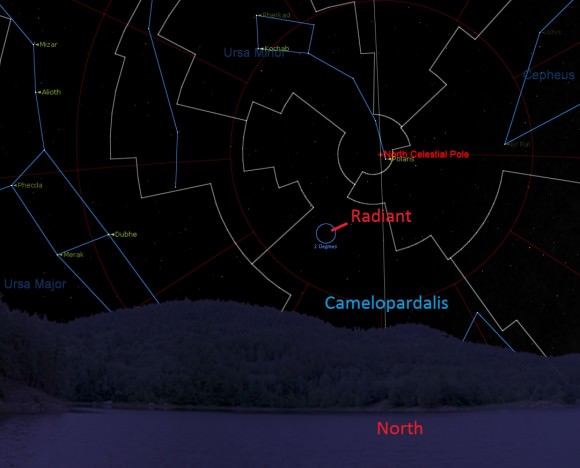

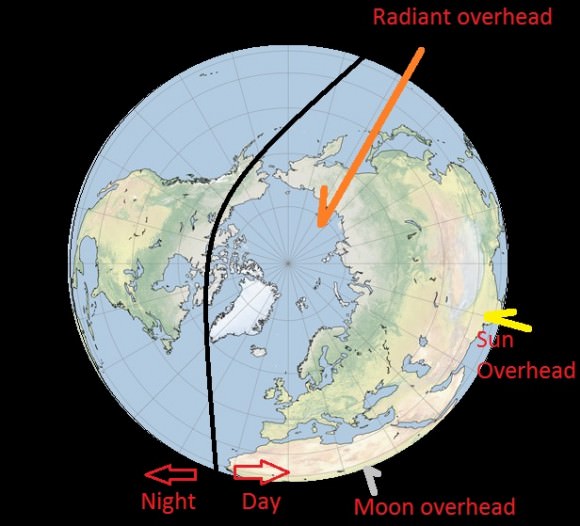

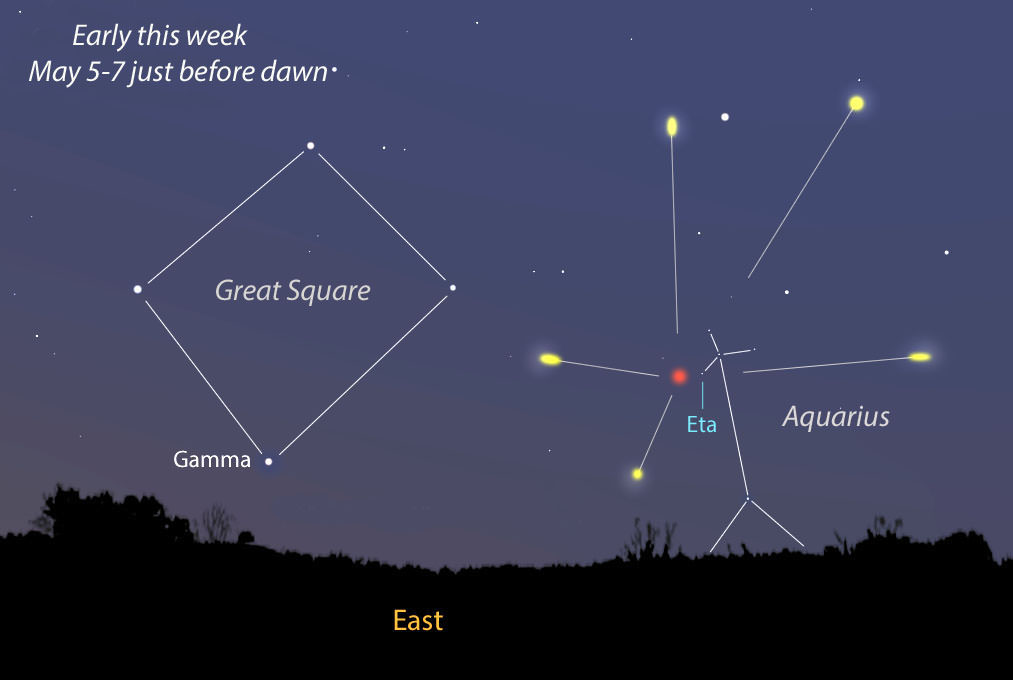

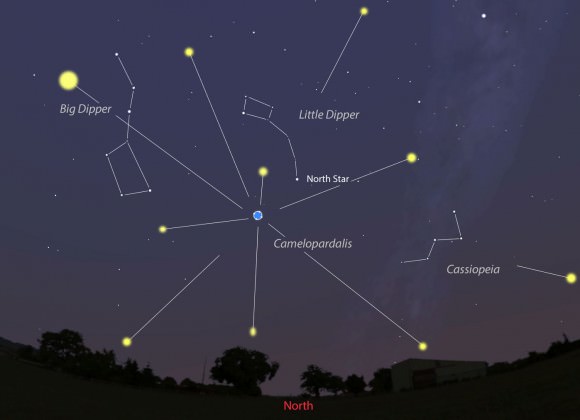

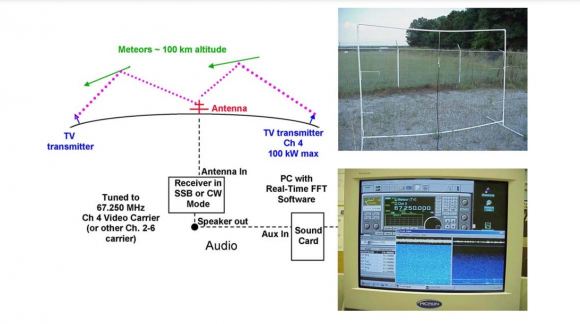

We’re grateful for the dust 209P/LINEAR carelessly lost during its many passes in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Earth is expected to pass through multiple filaments of debris overnight Friday May 23-24 with the peak of at least 100 meteors per hour – about as good as a typical Perseid or Geminid shower – occurring around 2 a.m. CDT (7 hours UT).

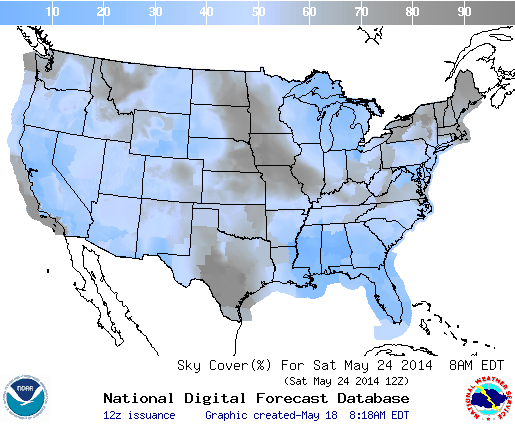

If it’s cloudy or you’re not in the sweet zone for viewing either the comet or the potential shower, astrophysicist Gianluca Masi will offer a live feed of the comet at the Virtual Telescope Project website scheduled to begin at 3 p.m. CDT (8 p.m. Greenwich Time) May 22. A second meteor shower live feed will start at 12:30 a.m. CDT (5:30 a.m. Greenwich Time) Friday night/Saturday morning May 23-24.

SLOOH will also cover 209P/LINEAR live on the Web with telescopes on the Canary Islands starting at 5 p.m. CDT (6 p.m. EDT, 4 p.m. MDT and 3 p.m. PDT) May 23. Live meteor shower coverage featuring astronomer Bob Berman of Astronomy Magazine begins at 10 p.m. CDT. Viewers can ask questions by using hashtag #slooh.

A very exciting weekend lies ahead!