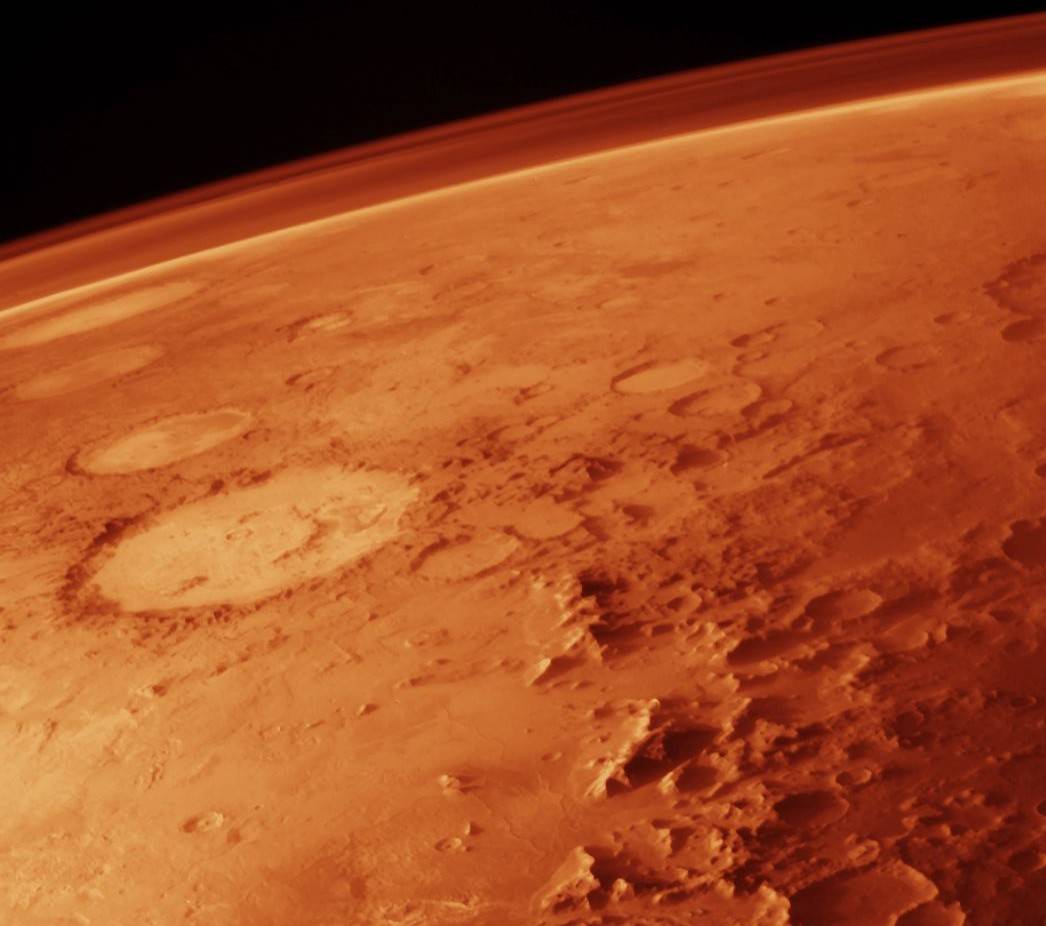

Mars is currently home to a small army robotic rovers, satellites and orbiters, all of which are busy at work trying to unravel the deeper mysteries of Earth’s neighbor. These include whether or not the planet ever had liquid water on its surface, what the atmosphere once looked like, and – most importantly of all – if it ever supported life.

And while much has been learned about Martian water and its atmosphere, the all-important question of life remains unanswered. Until such time as organic molecules – considered to be the holy grail for missions like Curiosity – are found, scientists must look elsewhere to find evidence of Martian life.

According to a recent paper submitted by an international team of scientists, that evidence may have arrived on Earth three and a half years ago aboard a meteorite that fell in the Moroccan desert. Believed to have broken away from Mars 700,000 years ago, so-called Tissint meteorite has internal features that researchers say appear to be organic materials.

The paper appeared in the scientific journal Meteoritics and Planetary Sciences. In it, the research team – which includes scientists from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL) – indicate organic carbon is located inside fissures in the rock. All indications are the meteorite is Martian in origin.

“So far, there is no other theory that we find more compelling,” says Philippe Gillet, director of EPFL’s Earth and Planetary Sciences Laboratory. He and his colleagues from China, Japan and Germany performed a detailed analysis of organic carbon traces from a Martian meteorite, and have concluded that they have a very probable biological origin.

The scientists argue that carbon could have been deposited into the fissures of the rock when it was still on Mars by the infiltration of fluid that was rich in organic matter.

If this sounds familiar, you may recall a previous Martian meteorite named ALH84001, found in the Allen Hills region in Antarctica. In 1996 NASA researchers announced they had found evidence within ALH84001 that strongly suggested primitive life may have existed on Mars more than 3.6 billion years ago. While subsequent studies of the now famous Allen Hills Meteorite shot down theories that the Mars rock held fossilized alien life, both sides continue to debate the issue.

This new research on the Tissint meteorite will likely be reviewed and rebutted, as well.

The researchers say the meteorite was likely ejected from Mars after an asteroid crashed on its surface, and fell to Earth on July 18, 2011, and fell in Morocco in view of several eyewitnesses.

Upon examination, the alien rock was found to have small fissures that were filled with carbon-containing matter. Several research teams have already shown that this component is organic in nature, but they are still debating where the carbon came from.

Chemical, microscopic and isotope analysis of the carbon material led the researchers to several possible explanations of its origin. They established characteristics that unequivocally excluded a terrestrial origin, and showed that the carbon content were deposited in the Tissint’s fissures before it left Mars.

This research challenges research proposed in 2012 that asserted that the carbon traces originated through the high-temperature crystallization of magma. According to the new study, a more likely explanation is that liquids containing organic compounds of biological origin infiltrated Tissint’s “mother” rock at low temperatures, near the Martian surface.

These conclusions are supported by several intrinsic properties of the meteorite’s carbon, e.g. its ratio of carbon-13 to carbon-12. This was found to be significantly lower than the ratio of carbon-13 in the CO2 of Mars’s atmosphere, previously measured by the Phoenix and Curiosity rovers.

Moreover, the difference between these ratios corresponds perfectly with what is observed on Earth between a piece of coal – which is biological in origin – and the carbon in the atmosphere.

The researchers note that this organic matter could also have been brought to Mars when very primitive meteorites – carbonated chondrites – fell on it. However, they consider this scenario unlikely because such meteorites contain very low concentrations of organic matter.

“Insisting on certainty is unwise, particularly on such a sensitive topic,” warns Gillet. “I’m completely open to the possibility that other studies might contradict our findings. However, our conclusions are such that they will rekindle the debate as to the possible existence of biological activity on Mars – at least in the past.”

Be sure to check out these videos from EPFL News, which include an interview with Philippe Gillet, EPFL and co-author of the study:

And this video explaining the history of the Tissint meteor:

Further Reading: EPFL