Finding planets beyond our Solar System is already tough, laborious work. But when it comes to confirmed exoplanets, an even more challenging task is determining whether or not these worlds have their own satellites – aka. “exomoons”. Nevertheless, much like the study of exoplanets themselves, the study of exomoons presents some incredible opportunities to learn more about our Universe.

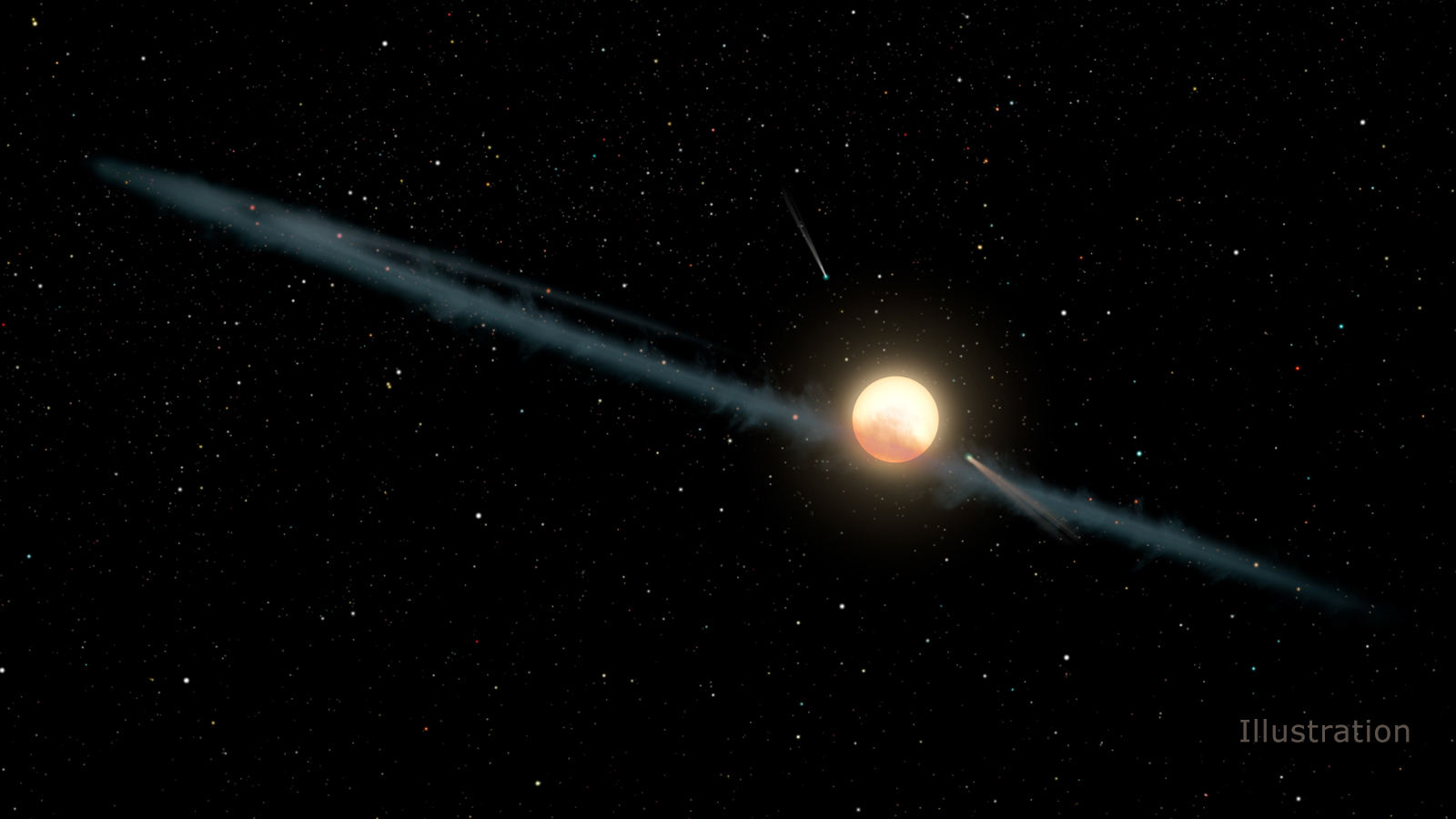

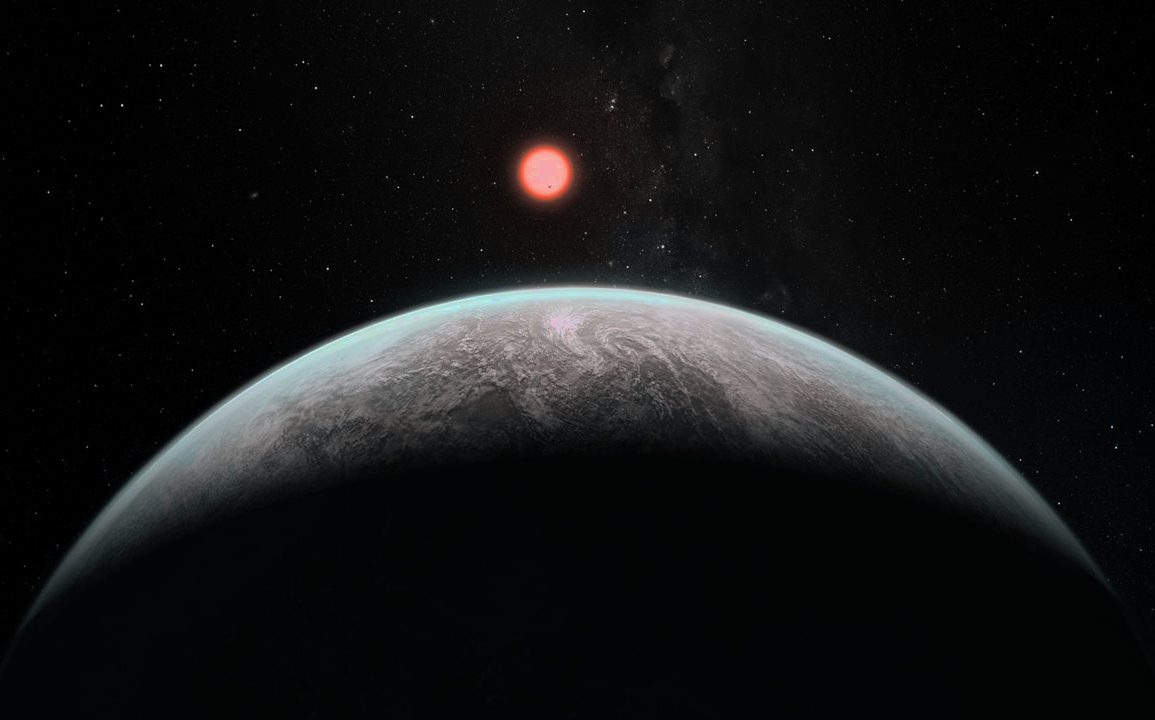

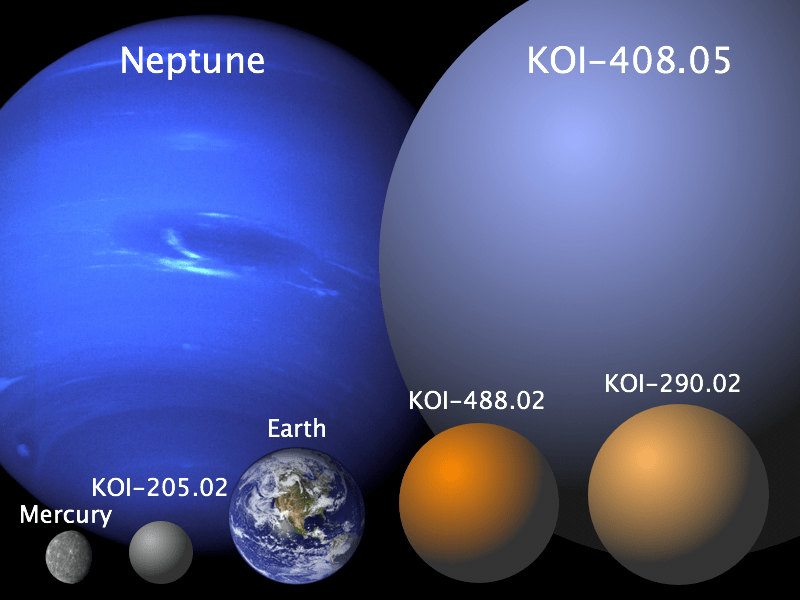

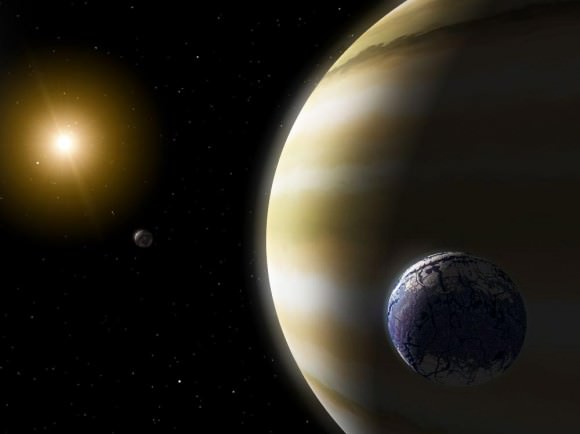

Of all possible candidates, the most recent (and arguably, most likely) one was announced back in July 2017. This moon, known as Kepler-1625 b-i, orbits a gas giant roughly 4,000 light years from Earth. But according to a new study, this exomoon may actually be a Neptune-sized gas giant itself. If true, this will constitute the first instance where a gas giant has been found orbiting another gas giant.

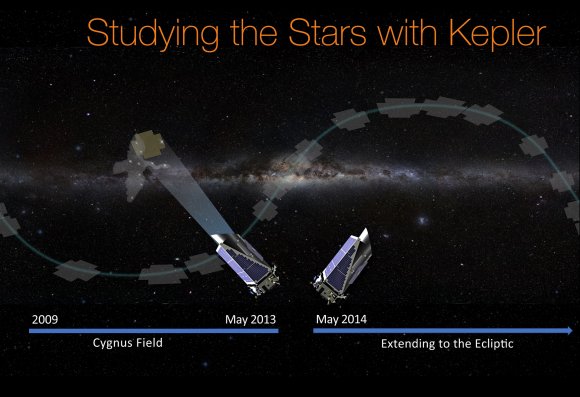

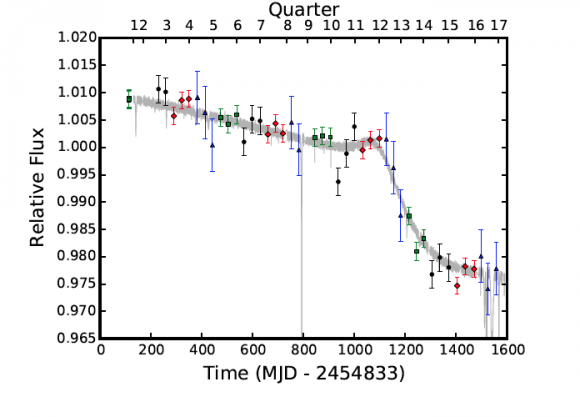

The study, titled “The Nature of the Giant Exomoon Candidate Kepler-1625 b-i“, recently appeared in the scientific journal Astronomy and Astrophysics. The study was conducted by René Heller, an astrophysicist from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, who examined lightcurves obtained by the Kepler mission to place constraints on the exomoon’s mass and determine its true nature.

Within the Solar System, moons tell us much about their host planet’s formation and evolution. In the same way, the study of exomoons is likely to provide insight into extra-solar planetary systems. As Dr. Heller explained to Universe Today via email, these studies could also shed light on whether or not these systems have habitable planets:

“Moons have proven to be extremely helpful to study the formation and evolution of the planets in the solar system. The Earth’s Moon, for example, was key to set the initial astrophysical conditions, such as the total mass of the Earth and the Earth’s primordial spin state, for what has become our habitable environment. As another example, the Galilean moons around Jupiter have been used to study the conditions of the primordial accretion disk around Jupiter from which the planet pulled its mass 4.5 billion years ago. This accretion disk has long gone, but the moons that formed within the disk are still there. And so we can use the moons, in particular their contemporary composition and water contents, to study planet formation in the far past.”

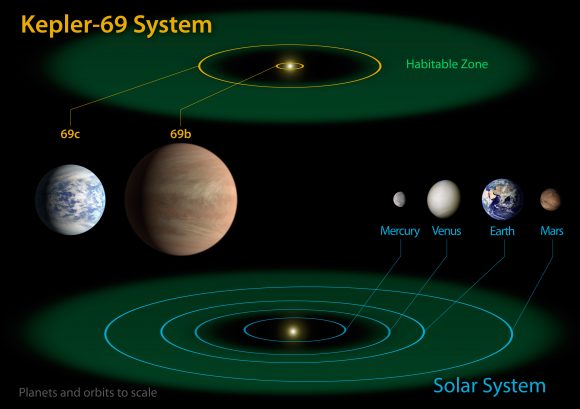

When it comes to the Kepler-1625 star system, previous studies were able to produce estimates of the radii of both Kepler-1625 b and its possible moon, based on three observed transits it made in front of its star. The light curves produced by these three observed transits are what led to the theory that Kepler-1625 had a Neptune-size exomoon orbiting it, and at a distance of about 20 times the planet’s radius.

But as Dr. Heller indicated in his study, radial velocity measurements of the host star (Kepler-1625) were not considered, which would have produced mass estimates for both bodies. To address this, Dr. Heller considered various mass regimes in addition to the planet and moon’s apparent sizes based on their observed signatures. Beyond that, he also attempted to place the planet and moon into the context of moon formation in the Solar System.

The first step, accroding to Dr. Heller, was to conduct estimates of the possible mass of the exomoon candidate and its host planet based on the properties that were shown in the transit lightcurves observed by Kepler.

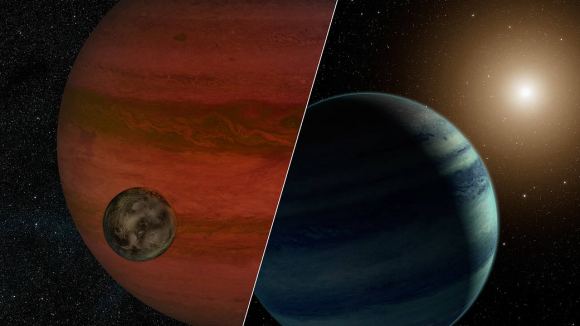

“A dynamical interpretation of the data suggests that the host planet is a roughly Jupiter-sized (“size” in terms of radius) brown dwarf with a mass of almost 18 Jupiter masses,” he said. “The uncertainties, however, are very large mostly due to the noisiness of the Kepler data and due to the low number of transits (three). In fact, the host object could be a Jupiter-like planet or even be a moderate-sized brown dwarf of up to 37 Jupiter masses. The mass of the moon candidate ranges somewhere between a super-Earth of a few Earth masses and Neptune’s mass.”

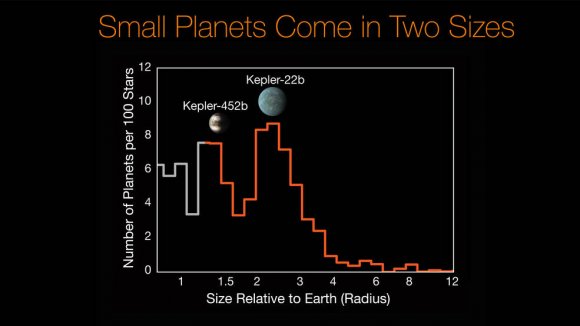

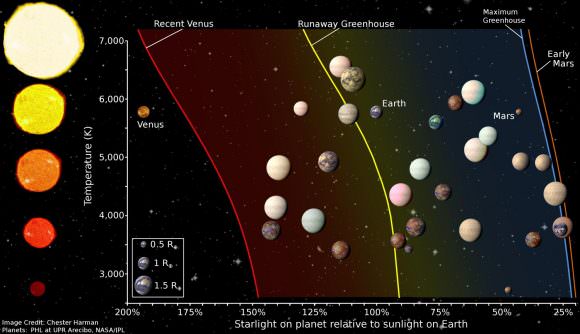

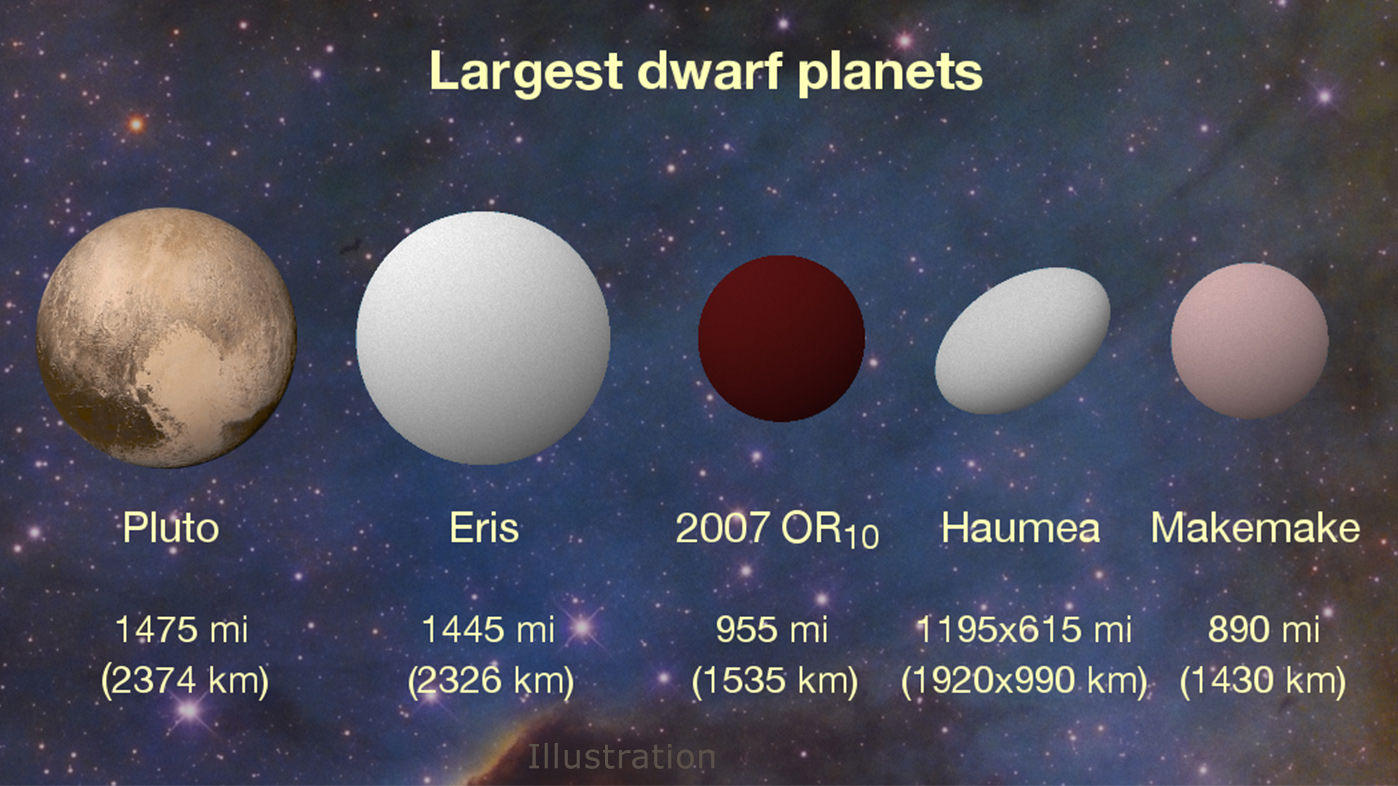

Next, Dr. Heller compared the relative mass of the exomoon candidate and Kepler-1625 b and compared this value to various planets and moons of the Solar System. This step was necessary because the moons of the Solar System show two distinct populations, based the mass of the planets compared to their moon-to-planet mass ratios. These comparisons indicate that a moon’s mass is closely related to how it formed.

For instance, moons that formed through impacts – such as Earth’s Moon, and Pluto’s moon Charon – are relatively heavy, whereas moons that formed from a planet’s accretion disk are relatively light. While Jupiter’s moon Ganymede is the most massive moon in the Solar System, it is rather diminutive and tiny compared to Jupiter itself – the largest and most massive body in the Solar System.

In the end, the results Dr. Heller obtained proved to be rather interesting. Basically, they indicated that Kepler-1625 b-i cannot be definitively placed in either of these families (heavy, impact moons vs. lighter, accretion moons). As Dr. Heller explained:

“[T]]he most reasonable scenarios suggest that the moon candidate is more of the heavy kind, which suggests it should have formed through an impact. However, this exomoon, if real, is most likely gaseous. The solar system moons are all rocky/icy bodies without a significant gas envelope (Titan has a thick atmosphere but its mass is negligible). So how would a gas giant moon have formed through an impact? I don’t know. I don’t know if anybody knows.

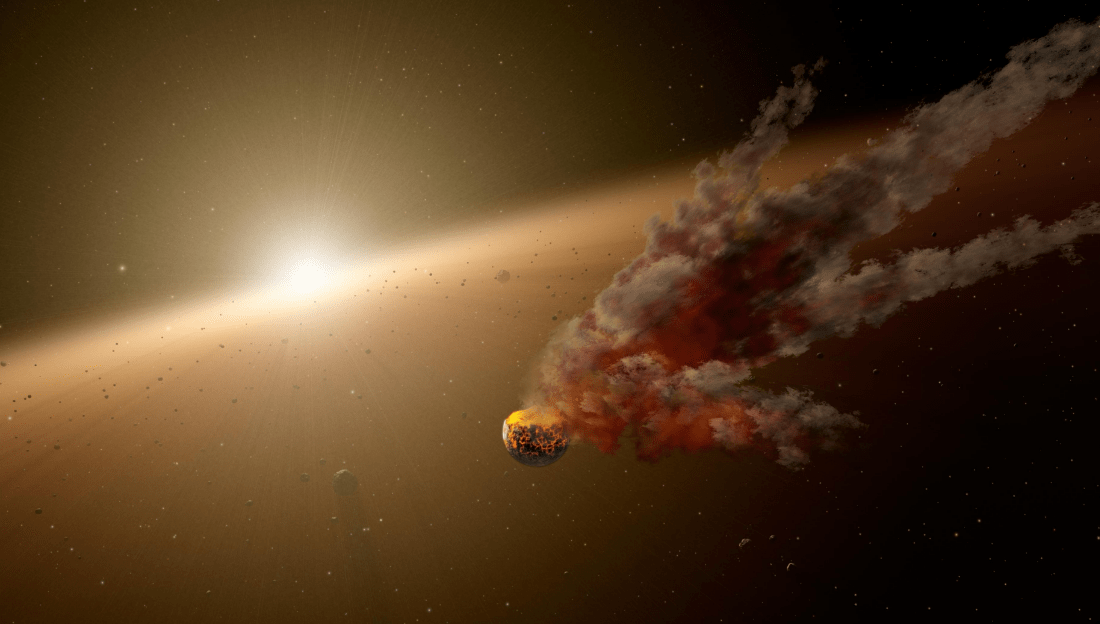

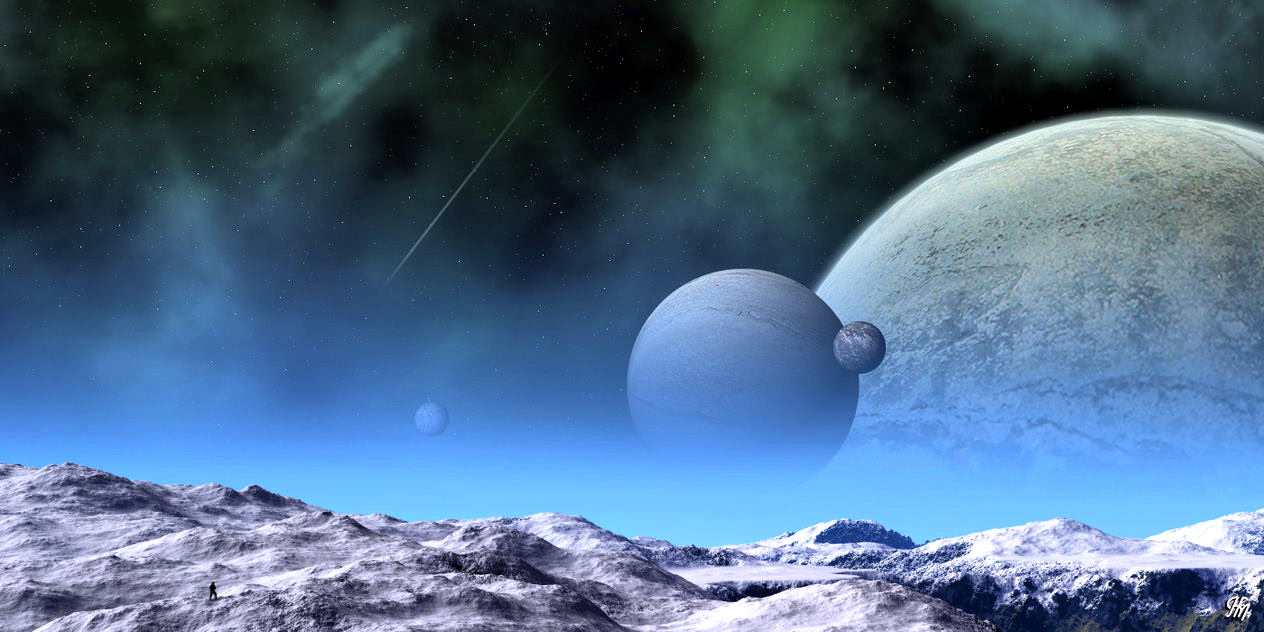

“Alternatively, in a third scenario, Kepler-1625 b-i could have formed through capture, but this implies a very unlikely progenitor planetary binary system, from which it was pulled into a bound orbit around Kepler-1625 b, while its former planetary companion was ejected from the system.”

What was equally interesting were the mass estimates for Keple-1625 b, which Dr. Heller averaged to be 19 Jupiter masses, but could be as high as 112 Jupiter Masses. This means that the host planet could be anything from a gas giant that is just slightly larger than Saturn to a Brown Dwarf or even a Very-Low-Mass-Star (VLMS). So rather than a gas giant moon orbiting a gas giant, we could be dealing with a gas giant moon orbiting a small star, which together orbit a larger star!

It’s the stuff science fiction is made of! And while this study cannot provide exact mass constraints on Keplder-1625 b and its possible moon, its significance cannot be denied. Beyond providing astrophysicists with the first possible example of a gas giant moon, this study is of immense significance as far as the study of exoplanet systems is concerned. If and when Kepler-1625 b-i is confirmed, it will tell us much about the conditions under which its host formed.

In the meantime, more observations are needed to confirm or rule out the existence of this moon. Fortunately, these observations will be taking place in the very near future. When Kepler-1625 b makes it next transit – on October 29th, 2017 – the Hubble Space Telescope will be watching! Based on the light curves it observes coming from the star, scientist should be able to get a better idea of whether or not this mysterious moon is real and what it looks like.

“If the moon turns out to be a ghost in the data, then most of this study would not be applicable to the Kepler-1625 system,” said Dr. Heller. “The paper would nevertheless present an example study of how to classify future exomoons and how to put them into the context of the solar system. Alternatively, if Kepler-1625 b-i turns out to be a genuine exomoon, then my study suggests that we have found a new kind of moon that has a very different formation history than the moons we know as of today. Certainly an exquisite riddle for astrophysicists to solve.”

The study of exoplanet systems is like pealing an onion, albeit in a dark room with the lights turned off. With every successive layer scientists peel back, the more mysteries they find. And with the deployment of next-generation telescopes in the near future, we are bound to learn a great deal more!

Further Reading: Astronomy and Astrophysics