[/caption]

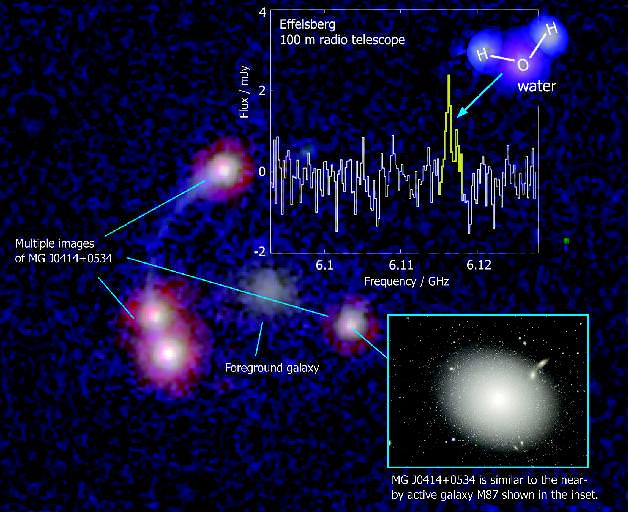

Astronomers have found the most distant signs of water in the Universe to date. The water vapor is thought to be contained in a maser, a jet ejected from a supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy, named MG J0414+0534. The radiation from the water maser was emitted when the Universe was only about 2.5 billion years old, a fifth of its current age. “The radiation that we detected has taken 11.1 billion years to reach the Earth, said Dr. John McKean of the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON). “However, because the Universe has expanded like an inflating balloon in that time, stretching out the distances between points, the galaxy in which the water was detected is about 19.8 billion light years away.”

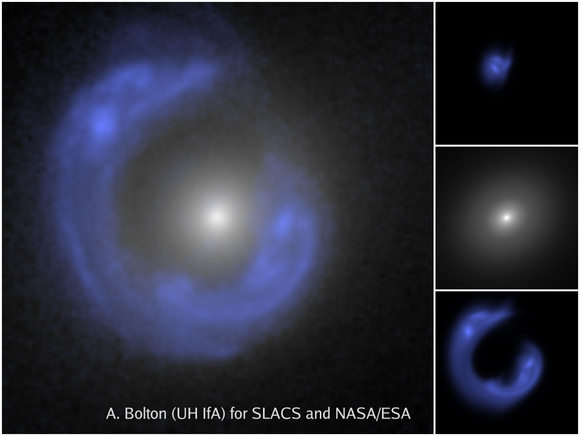

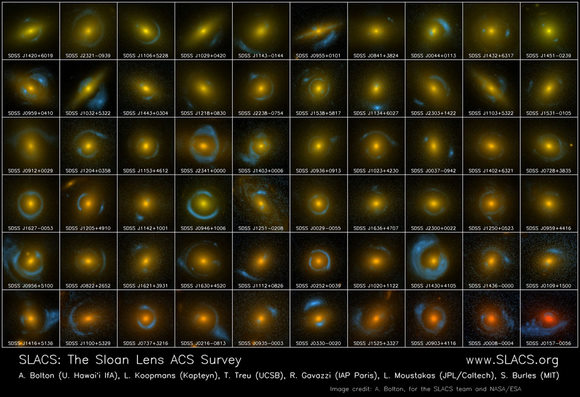

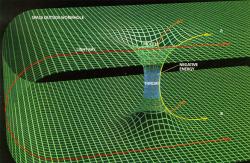

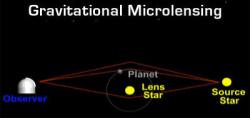

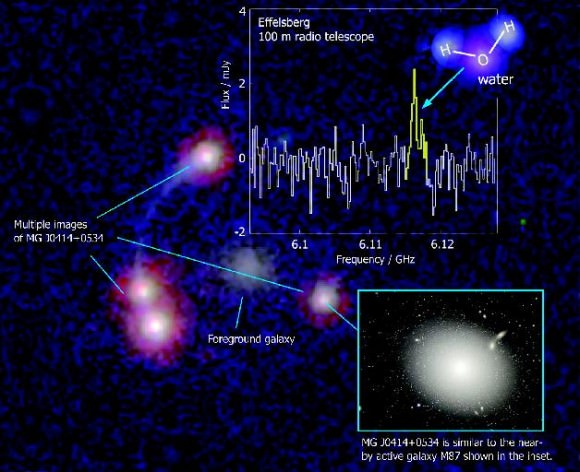

The water emission is seen as a maser, where molecules in the gas amplify and emit beams of microwave radiation in much the same way as a laser emits beams of light. The faint signal is only detectable by using a technique called gravitational lensing, where the gravity of a massive galaxy in the foreground acts as a cosmic telescope, bending and magnifying light from the distant galaxy to make a clover-leaf pattern of four images of MG J0414+0534. The water maser was only detectable in the brightest two of these images.

“We have been observing the water maser every month since the detection and seen a steady signal with no apparent change in the velocity of the water vapor in the data we’ve obtained so far, McKean said. “This backs up our prediction that the water is found in the jet from the supermassive black hole, rather than the rotating disc of gas that surrounds it.”

Although since the initial discovery the team has looked at five more systems that have not had water masers, they believe that it is likely that there are many more similar systems in the early Universe. Surveys of nearby galaxies have found that only about 5% have powerful water masers associated with active galactic nuclei. In addition, studies show that very powerful water masers are extremely rare compared to their less luminous counterparts. The water maser in MG J0414+0534 is about 10,000 times the luminosity of the Sun, which means that if water masers were equally rare in the early Universe, the chances of making this discovery would be improbably slight.

“We found a signal from a really powerful water maser in the first system that we looked at using the gravitational lensing technique. From what we know about the abundance of water masers locally, we could calculate the probability of finding a water maser as powerful as the one in MG J0414+0534 to be one in a million from a single observation. This means that the abundance of powerful water masers must be much higher in the distant Universe than found locally because I’m sure we are just not that lucky!” said Dr McKean.

The discovery of the water maser was made by a team led by Dr. Violette Impellizzeri using the 100-metre Effelsberg radio telescope in Germany during July to September 2007. The discovery was confirmed by observations with the Expanded Very Large Array in the USA in September and October 2007. The team included Alan Roy, Christian Henkel and Andreas Brunthaler, from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, Paola Castangia from Cagliari Observatory and Olaf Wucknitz from the Argelander Institute for Astronomy at Bonn University. The findings were published in Nature in December 2008.

The team is now analyzing high-resolution data to find out how close the water maser lies to the supermassive black hole, which will give them new insights into the structure at the center of active galaxies in the early Universe.

“This detection of water in the early Universe may mean that there is a higher abundance of dust and gas around the super-massive black hole at these epochs, or it may be because the black holes are more active, leading to the emission of more powerful jets that can stimulate the emission of water masers. We certainly know that the water vapour must be very hot and dense for us to observe a maser, so right now we are trying to establish what mechanism caused the gas to be so dense,” said Dr McKean.

McKean presented the team’s findings at the European Week of Astronomy and Space Science in the UK this week.

Source: RAS