[/caption]

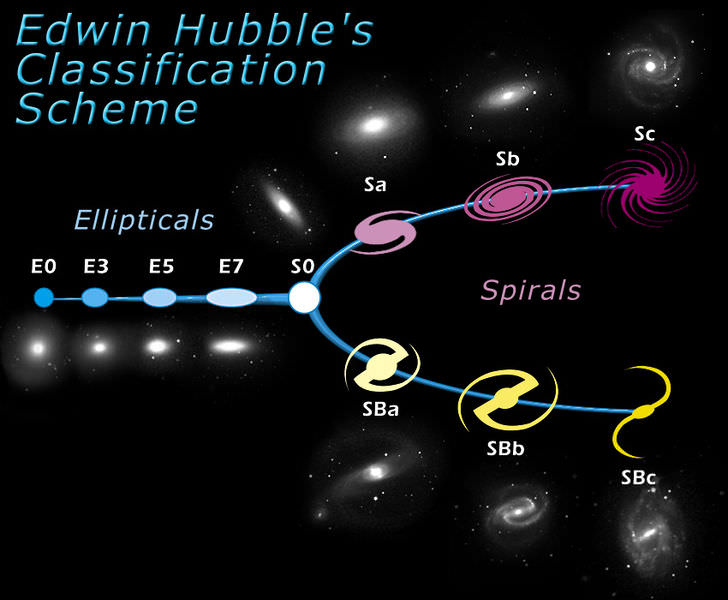

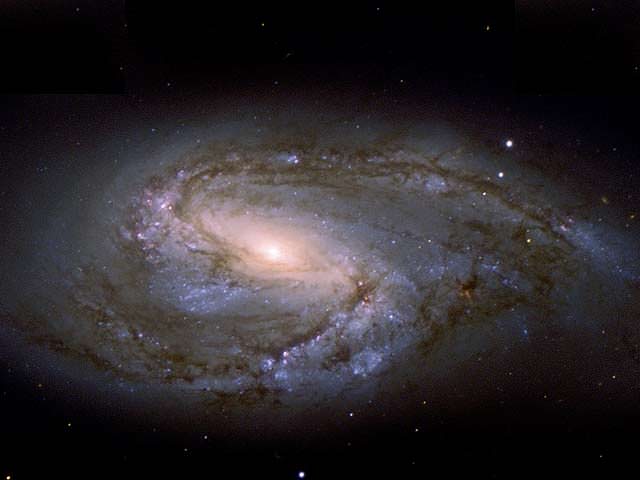

In 1926, astronomer Edwin Hubble gave us our first basic galaxy classification scenario – the Hubble Sequence. Using photographic plates, Hubble derived a simplistic system based on three visually known structures: elipitical, spiral and lenticular. This sequence, when plotted out, gave the appearance of a common object and eventually became known as the “Hubble Tuning Fork” (as seen above). For many decades, this served as a standard. Now the ATLAS3D Project is calling a different tune…

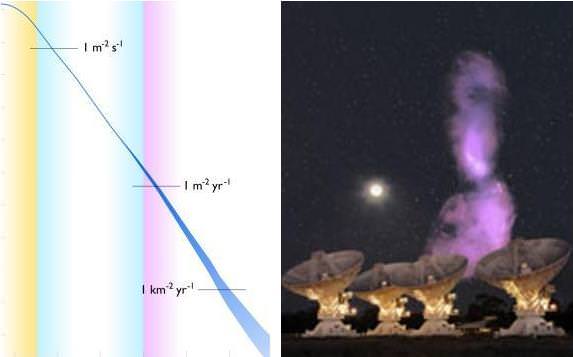

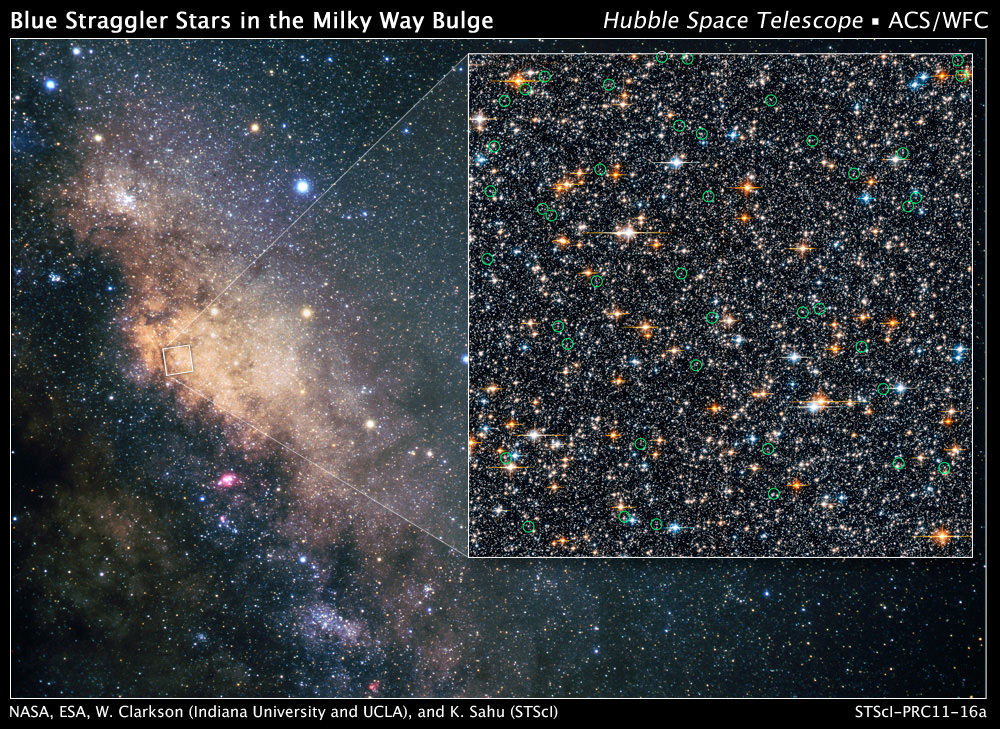

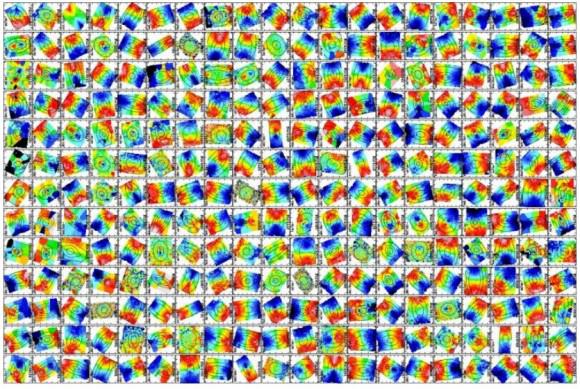

Just who is the pied piper in this merry band? The ATLAS3D project is a multiwavelength survey combined with a theoretical modelling effort. The observations it takes spans from the radio to the millimetre and optical. It provides multicolor imaging, as well as two-dimensional kinematics of the atomic, molecular and ionized gases, together with the kinematics and population of the stars, Where does it dance? Only around a carefully selected, volume-limited sample of 260 early-type galaxies.

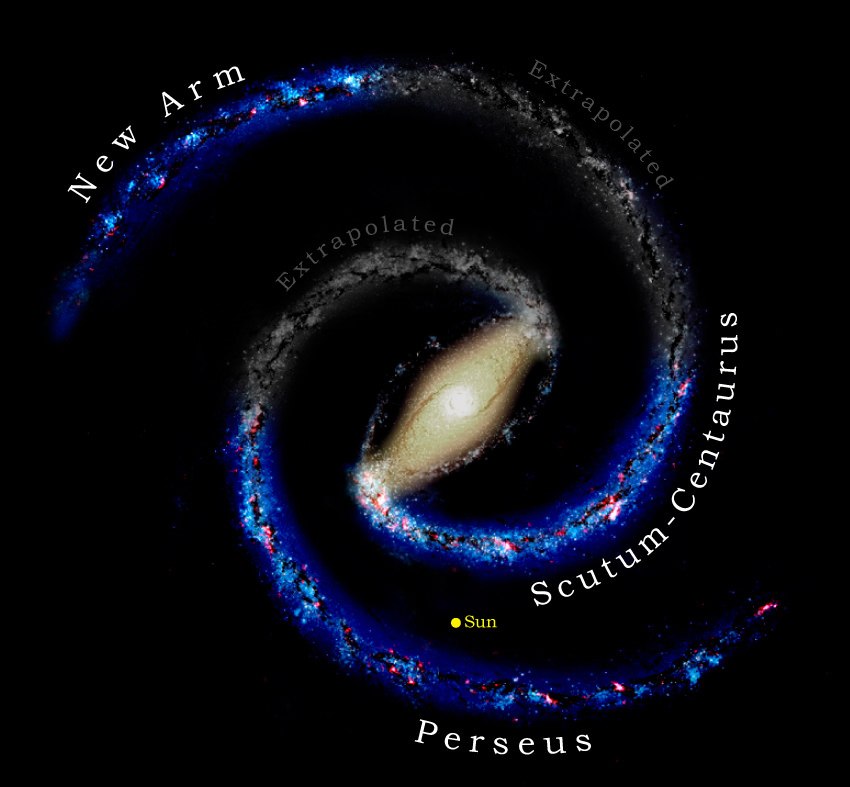

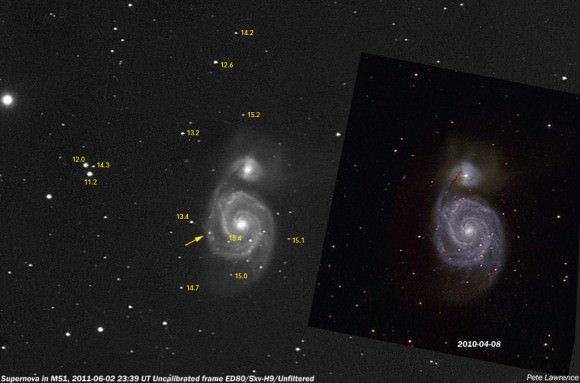

Heading up the project is a team of 25 astronomers from Europe and Northern America, including ASTRON astronomers Morganti, Oosterloo, and Serra – and all with a mission – to update and revise our understanding of galactic evolution. Employing the SAURON spectrograph on the 4.2-meter William Herschel Telescope on La Palma, the team was able to distinguish stellar movement in the pre-determined galactic candidates. These new assessments show that spheroid galaxies belong to the spiral galaxy classification. How did they come to that conclusion? The largest portion of spheroids – or early types – are basically the same family as spirals and evolve along a similar line. But with ATLAS3D findings, we’re looking at new concepts.

We’re seeing beyond the optical (photographic plates) which founded Hubble’s original diagram – where once galaxies were separated by their distinct characteristics such as rapid rotators rich in stars and gas – or as slowly moving, gas-poor models. Up until now, it was also next to impossible to distinguish sparse “face-on” structure from edge-on spheroids. With the aid of kinematic data astronomers can “see” rotation – allowing observation of all galaxy types from any angle.

“Slow and fast rotators tend to be classified as ellipticals and lenticulars, respectively, but the contamination is strong enough to affect results solely based on such a scheme: 20 per cent of all fast rotators are classified as ellipticals, and more importantly 66 per cent of all ellipticals in the ATLAS3D sample are fast rotators.” says the team. “Our complete sample of 260 ETGs leads to a new criterion to disentangle fast and slow rotators which now includes a dependency on the apparent ellipticity. It separates the two classes significantly better than the previous prescription.”

While it will take many years and many more observations to sort out all the new data, it would seem that our current understanding of galactic evolution just might need a “tune up”.

Oringinal Story Source: ASTRON.