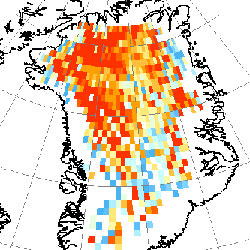

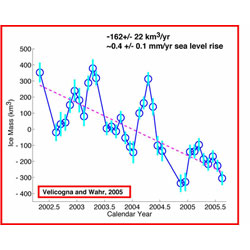

Decreasing levels of ice thickness from Greenland. Image credit: NASA/JPL. Click to enlarge.

In the first direct, comprehensive mass survey of the entire Greenland ice sheet, scientists using data from the NASA/German Aerospace Center Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (Grace) have measured a significant decrease in the mass of the Greenland ice cap. Grace is a satellite mission that measures movement in Earth’s mass.

In an update to findings published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, a team led by Dr. Isabella Velicogna of the University of Colorado, Boulder, found that Greenland’s ice sheet decreased by 162 (plus or minus 22) cubic kilometers a year between 2002 and 2005. This is higher than all previously published estimates, and it represents a change of about 0.4 millimeters (.016 inches) per year to global sea level rise.

“Greenland hosts the largest reservoir of freshwater in the northern hemisphere, and any substantial changes in the mass of its ice sheet will affect global sea level, ocean circulation and climate,” said Velicogna. “These results demonstrate Grace’s ability to measure monthly mass changes for an entire ice sheet ? a breakthrough in our ability to monitor such changes.”

Other recent Grace-related research includes measurements of seasonal changes in the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, Earth’s strongest ocean current system and a very significant force in global climate change. The Grace science team borrowed techniques from meteorologists who use atmospheric pressure to estimate winds. The team used Grace to estimate seasonal differences in ocean bottom pressure in order to estimate the intensity of the deep currents that move dense, cold water away from the Antarctic. This is the first study of seasonal variability along the full length of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, which links the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Dr. Victor Zlotnicki, an oceanographer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., called the technique a first step in global satellite monitoring of deep ocean circulation, which moves heat and salt between ocean basins. This exchange of heat and salt links sea ice, sea surface temperature and other polar ocean properties with weather and climate-related phenomena such as El Ninos. Some scientific studies indicate that deep ocean circulation plays a significant role in global climate change.

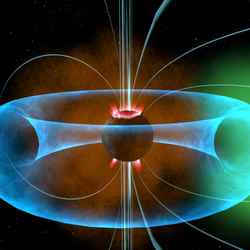

The identical twin Grace satellites track minute changes in Earth’s gravity field resulting from regional changes in Earth’s mass. Masses of ice, air, water and solid Earth can be moved by weather patterns, seasonal change, climate change and even tectonic events, such as this past December’s Sumatra earthquake. To track these changes, Grace measures micron-scale changes in the 220-kilometer (137-mile) separation between the two satellites, which fly in formation. To limit degradation of Grace’s satellite antennas due to atomic oxygen exposure and thereby preserve mission life, a series of maneuvers was performed earlier this month to swap the satellites’ relative positions in orbit.

In a demonstration of the satellites’ sensitivity to minute changes in Earth’s mass, the Grace science team reported that the satellites were able to measure the deformation of the Earth’s crust caused by the December 2004 Sumatra earthquake. That quake changed Earth’s gravity by one part in a billion.

Dr. Byron Tapley, Grace principal investigator at the University of Texas at Austin, said that the detection of the Sumatra earthquake gravity signal illustrates Grace’s ability to measure changes on and within Earth’s surface. “Grace’s measurements will add a global perspective to studies of large earthquakes and their impacts,” said Tapley.

Grace is managed for NASA by JPL. The University of Texas Center for Space Research has overall mission responsibility. GeoForschungsZentrum Potsdam, or GFZ, Potsdam, Germany, is responsible for German mission elements. Science data processing, distribution, archiving and product verification are managed jointly by JPL, the University of Texas and GFZ.

Imagery related to these latest Grace findings may be viewed at: http://www.nasa.gov/vision/earth/lookingatearth/grace-images-20051220.html .

For more information on Grace, visit: http://www.csr.utexas.edu/grace or http://www.gfz-potsdam.de/grace .

Original Source: NASA News Release