While new rockets and human missions to the Moon are in the press, NASA is quietly thinking through the nuts and bolts of a long-term presence on the Moon. They have already released two white papers about the lunar logistics they’ll require in the future and are now requesting proposals from companies to supply some serious cargo transportation. But this isn’t just for space transport; NASA is also looking for ground transportation on the Moon that can move cargo weighing as much as 2,000 to 6,000 kg (4,400 to 13,000 pounds.)

Continue reading “NASA Wants to Move Heavy Cargo on the Moon”Rocket Lab Launches NASA’s CAPSTONE Mission to the Moon

A microwave oven–sized cubesat launched to space today from New Zealand by commercial company Rocket Lab and their Electron rocket. The small satellite will conduct tests to make sure the unique lunar orbit for NASA’s future Lunar Gateway is actually stable.

The Cislunar Autonomous Positioning System Technology Operations and Navigation Experiment, or CAPSTONE, mission launched at 5:55 a.m. EDT (09:55 UTC) on Tuesday June 28 from the Rocket Lab Launch Complex 1 on the Mahia Peninsula of New Zealand. The Electron has now flown 27 times with 24 successes and 3 failures.

Continue reading “Rocket Lab Launches NASA’s CAPSTONE Mission to the Moon”Canada's Criminal Laws now Extend to Earth Orbit and the Moon

In this decade and the next, astronauts will be going to space like never before. This will include missions beyond Low Earth Orbit (LEO) for the first time in over fifty years, renewed missions to the Moon, and crewed missions to Mars. Beyond that, new space stations will be deployed to replace the aging International Space Station (ISS), and there are even plans to establish permanent human outposts on the Lunar and Martian surfaces.

In anticipation of humanity’s growing presence in space, and all that it will entail, legal scholars and authorities worldwide are looking to extend Earth’s laws into space. In a recent decision, the Canadian government introduced legislation extending Canada’s criminal code to the Moon. The amendment was part of the Budget Implementation Act (a 443-page document) tabled and passed late last month in Canada’s House of Commons.

Continue reading “Canada's Criminal Laws now Extend to Earth Orbit and the Moon”Lunar Gateway Will Maintain its Orbit With a 6 kW ion Engine

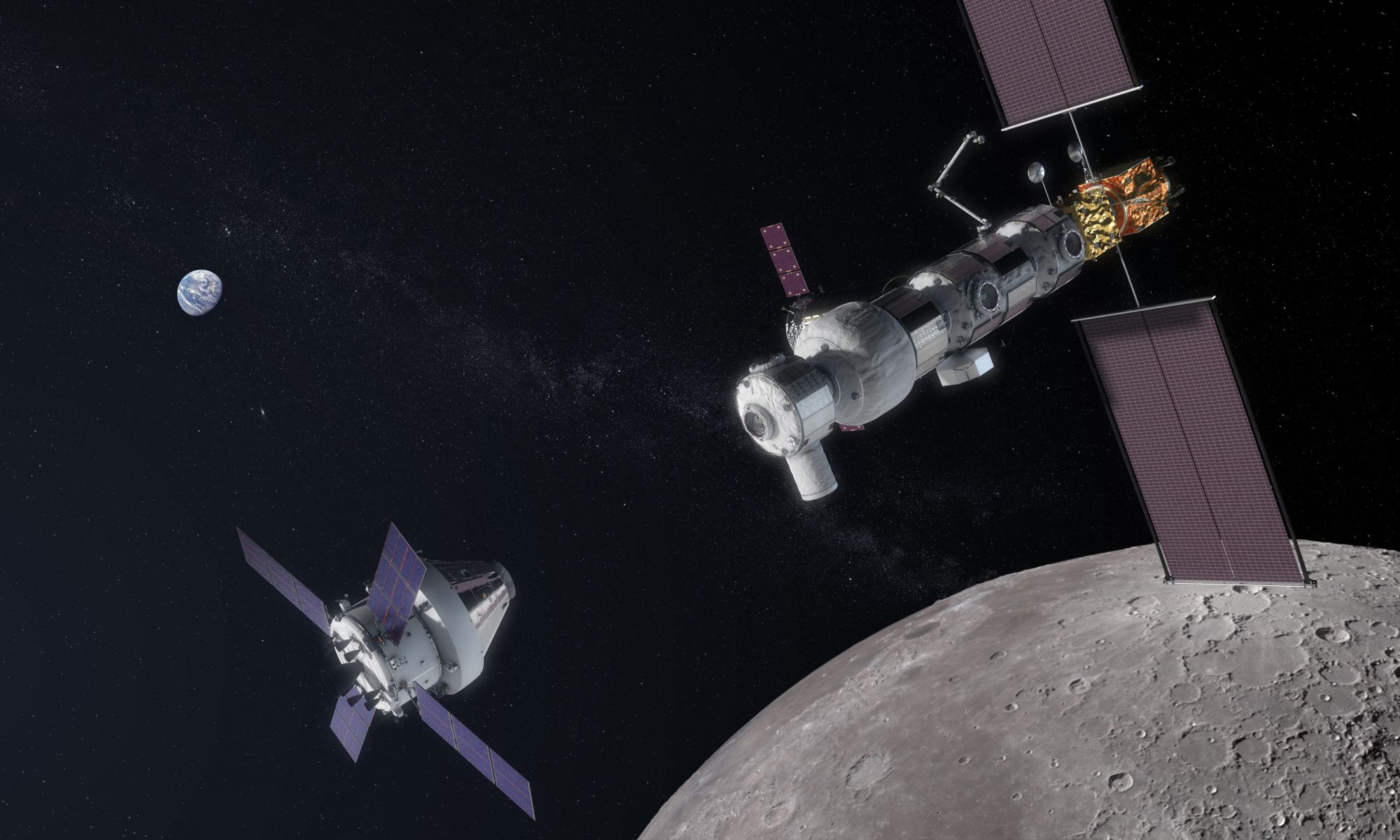

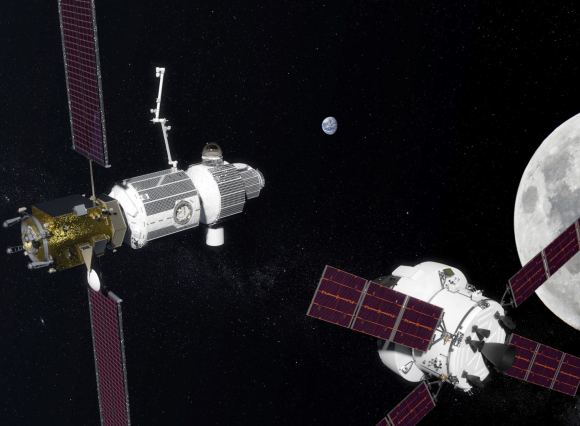

When NASA sends astronauts back to the Moon as part of the Artemis Program, they will be taking the long view. Rather than being another “footprints and flags” program, the goal is to create a lasting infrastructure that will ensure a “sustained program of lunar exploration.” A major element in this plan is the Lunar Gateway, an orbital habitat that astronauts will use to venture to and from the surface.

The first step in establishing the Gateway is the deployment of two critical modules – the Habitation and Logistics Outpost (HALO) and the Power and Propulsion Element (PPE). According to a recent update, NASA (along with Maxar Technologies and Busek Co.) recently completed a hot-fire test of the PPE propulsion subsystem – the first of many that will ensure that the PPE and HALO will be ready for launch by 2024.

Continue reading “Lunar Gateway Will Maintain its Orbit With a 6 kW ion Engine”Lunar Gateway Could be Built With the Falcon Heavy

In March of 2019, NASA was directed by the White House to land human beings on the Moon within five years. Known as Project Artemis, this expedited timeline has led to a number of changes and shakeups at NASA, not the least of which has to do with the deprioritizing of certain elements. Nowhere is this more clear than with the Lunar Gateway, an orbital habitat that NASA will be deploying to cislunar space in the coming years.

Originally, the Gateway was a crucial part of the agency’s plan to create a program of “sustainable lunar exploration.” In March of this year, NASA announced that the Lunar Gateway is no longer a priority and that Artemis will rely on an integrated lunar lander instead. However, NASA still hopes to build the Gateway, and according to a recent interview with ArsTechnica, this could be done with the help of SpaceX and the Falcon Heavy.

Continue reading “Lunar Gateway Could be Built With the Falcon Heavy”Lockheed Martin Shows off its new Space Habitat

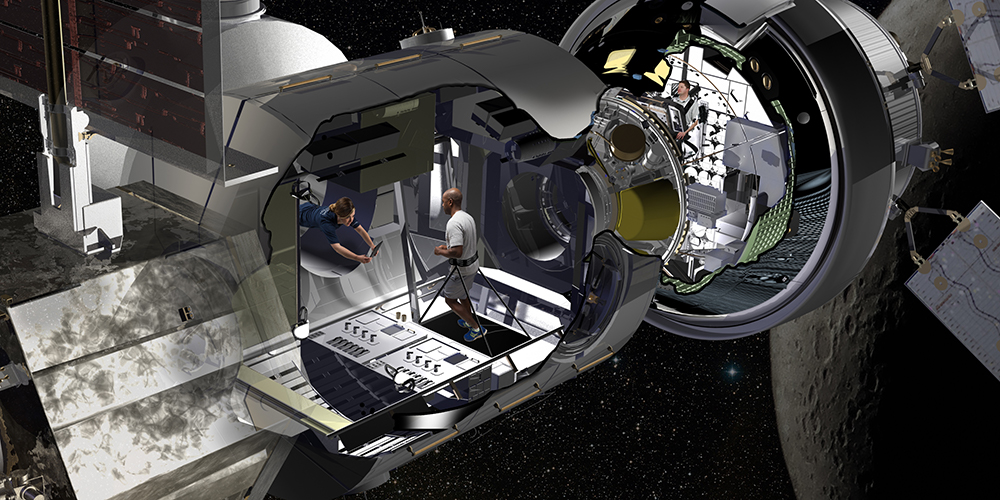

In their pursuit of returning astronauts to the Moon, and sending crewed missions to Mars, NASA has contracted with a number of aerospace companies to develop all the infrastructure it will need. In addition to the Space Launch System (SLS) and the Orion spacecraft – which will fly the astronauts into space and see them safety to their destinations – they have teamed up with Lockheed Martin and other contractors to develop the Deep Space Gateway.

This orbiting lunar habitat will not only facilitate missions to and from the Moon and Mars, it will also allow human beings to live and work in space like never before. On Thursday, August 16th, Lockheed Martin provided a first glimpse of what one the of habitats aboard the Deep Space Gateway would look like. It all took place at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where attendees were given a tour of the habitat prototype.

At it’s core, the habitat uses the Donatello Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM), a refurbished module designed by the Italian Space Agency that dates back to the Space Shuttle era. Like all MPLMs, the Donatello is a pressurized module that was intended to carry equipment, experiments and supplies to and from the International Space Station aboard the Space Shuttle.

While the Donatello was never sent into space, Lockheed Martin has re-purposed it to create their prototype habitat. Measuring 6.7 meters (22 feet) long and 4.57 meters (15 feet) wide, the pressurized capsule is designed to house astronauts for a period of 30 to 60 days. According to Bill Pratt, the program’s manager, it contains racks for science, life support systems, sleep stations, exercise machines, and robotic workstations.

The team also relied on “mixed-reality prototyping” to create the prototype habitat, a process where virtual and augmented reality are used to solve engineering issues in the early design phase. As Pratt explained in an interview with the Orlando Sentinel, their design makes optimal use of limited space, and also seeks to reuse already-build components:

“You think of it as an RV in deep space. When you’re in an RV, your table becomes your bed and things are always moving around, so you have to be really efficient with the space. That’s a lot of what we are testing here… We want to get to the moon and to Mars as quickly as possible, and we feel like we actually have a lot of stuff that we can use to do that.”

This habitat is one of several components that will eventually go into creating the Deep Space Gateway. These will include the habitat, an airlock, a propulsion module, a docking port and a power bus, which together would weigh 68 metric tonnes (75 US tons). This makes it considerably smaller than the International Space Station (ISS), which weighs in at a hefty 408 metric tonnes (450 US tons).

Moreover, the DSG is one of several components that will be used to return astronauts to the Moon and to Mars. As noted, these include the Space Launch System (SLS), which will be the most powerful launch vehicle since the Saturn V (the rocket that carried the Apollo astronauts to the Moon) and the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (MPCV), which will house the crew.

However, for their planned missions to Mars, NASA is also looking to develop the Deep Space Transport and the Mars Base Camp and Lander. The former calls for a reusable vehicle that would rely on a combination of Solar Electric Propulsion (SEP) and chemical propulsion to transport crews to and from the Gateway, whereas the latter would orbit Mars and provide the means to land on and return from the surface.

All told, NASA has awarded a combined $65 million to six contractors – Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Sierra Nevada Corp.’s Space Systems, Orbital ATK, NanoRacks and Bigelow Aerospace – to build the habitat prototype by the end of the year. The agency will then review the proposals to determine which systems and interfaces will be incorporated into the design of the Deep Space Gateway.

In the meantime, development of the Orion spacecraft continues at the Kennedy Space Center, which recently had its heat shields attached. Next month, the European Space Agency (ESA) will also be delivering the European Service Module to the Kennedy Space Center, which will be integrated with the Orion crew module and will provide it with the electricity, propulsion, thermal control, air and water it will need to sustain a crew in space.

Once this is complete, NASA will begin the process of integrating the spacecraft with the SLS. NASA hopes to conduct the first uncrewed mission using the Orion spacecraft by 2020, in what is known as Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1). Exploration Mission-2 (EM-2), which will involve a crew performing a lunar flyby test and returning to Earth, is expected to take place by mid-2022.

Development on the the Deep Space Transport and the Mars Base Camp and Lander is also expected to continue. Whereas the Gateway is part of the first phase of NASA’s “Journey to Mars” plan – the “Earth Reliant” phase, which involves exploration near the Moon using current technologies – these components will be part of Phase II, which is on developing long-duration capabilities beyond the Moon.

If all goes according to plan, and depending on the future budget environment, NASA still hopes to mount a crewed mission to Mars by the 2030s.

Further Reading: Orlando Sentinel

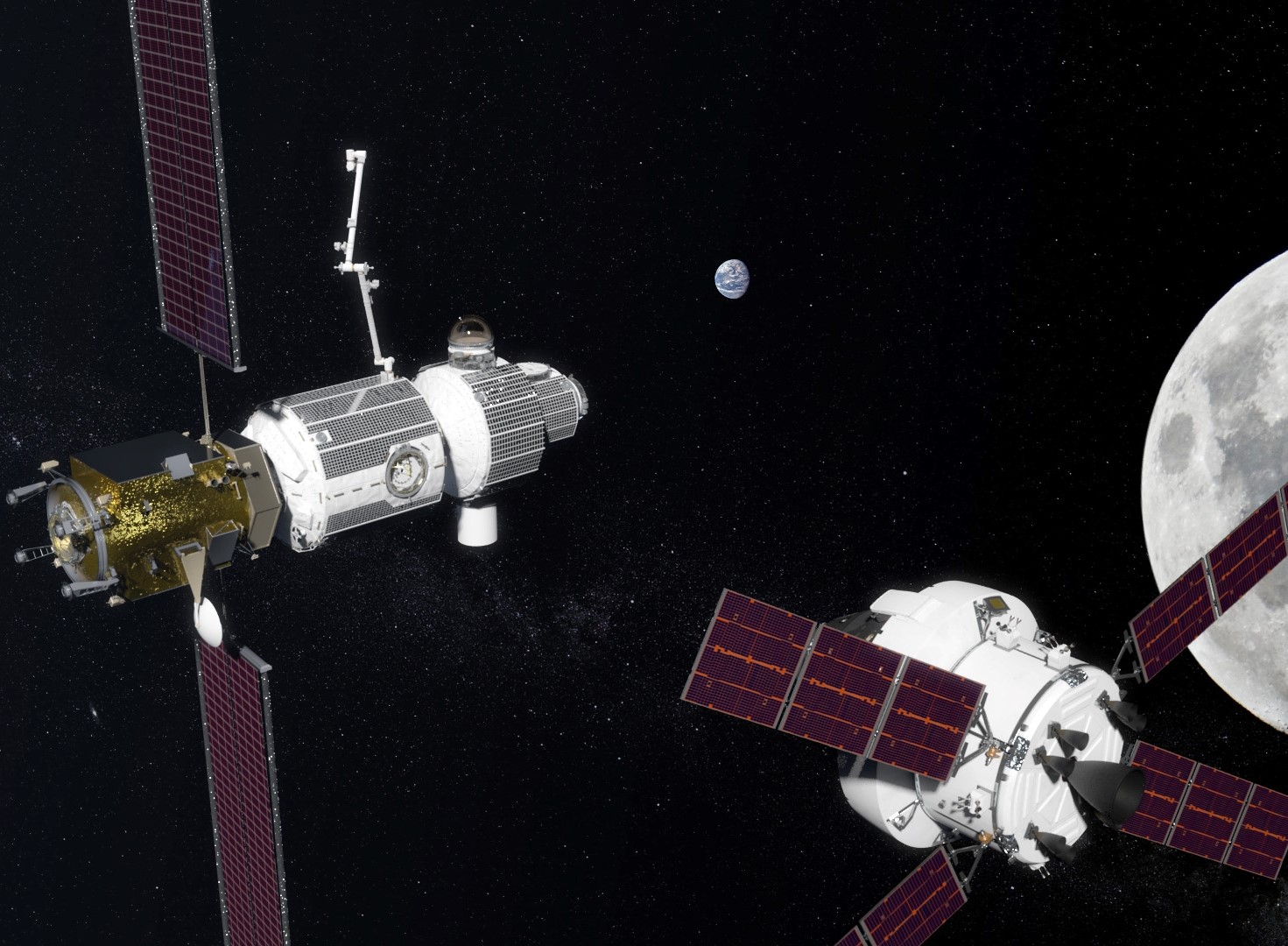

Russia Says They’ll Be Pitching in on the Deep Space Gateway

In Spring of 2017, NASA revealed their plans for what the massive Space Launch System (SLS) rocket would be used for: to build the Deep Space Gateway, a space station in cis-lunar orbit that’ll serve as a stepping stone to the exploration of the Solar System. Until today, it was assumed that this would be a NASA project, with the agency constructing the station over the course of several launches of the SLS from 2021 through 2026, delivering the 4 major modules. The details were hazy, though, with the various components in development with various contractors.

Today, however, NASA and the Russian Space Agency Roscosmos announced that they’ll be building the Deep Space Gateway together. They signed an agreement in Australia at the 68th International Astronautical Congress in Adelaide, Australia, and announced the news to the world.

What will Russia be contributing? According to TASS, Russian officials said that they’d be providing one to three modules for the station, as well as the docking mechanism that spacecraft would use when approaching the station. Russia also offered to carry some of the station parts on their new super heavy lift rocket. They didn’t specify the rocket, but that sounds like the Angara rocket which is in development, and is expected to make its first flights over the next few years.

The Deep Space Gateway will serve as the primary destination for NASA’s human space exploration efforts, once the SLS and Orion Crew Module are completed. The first launch of SLS will carry an unmanned Orion capsule on a trans-lunar flight in 2018. Then SLS will be used to blast the Europa Clipper off to the Jovian system. Their original strategy was to launch some time between 2021 and 2023 carrying the Solar Power Electric Bus module to the station, followed by the Habitation Module in 2024, the Logistics Module in 2025 and finally the Airlock Module in 2026.

At this point, NASA has solicited proposals from various aerospace contractors for the development of the Power Module, and Habitation System, and they didn’t indicate that Russia’s involvement would have any impact on the construction of these modules.

With the Russians announcing their involvement, we don’t really know how this’ll impact the structure of the station or its configuration of modules. This might also be an incentive for other space agencies (like the newly announced Australian Space Agency) to come on board.

Of course, the Russians were involved in the construction of the International Space Station. They provided the Zarya module for propulsion and navigational guidence, then the Zvezda for living quarters, and the Pirs, Poisk and Rassvet docking modules. They’ve also provided half the support of the station, including astronauts, and provide the only way to get humans up to the station, on their Soyuz rockets. Until recently, Russia had been threatening to pull their support of the International Space Station, before it was ready for retirement. But earlier this year, they agreed to support ISS until 2024, and even to 2028 if necessary. They’ve also been continuing work on their Multi-Purpose Laboratory Module (MLM), which was originally planned for launch in 2007, and is now expected to be attached to the station some time in 2018.

Before announcing their involvement with the Deep Space Gateway, Russia had said that they’d probably be investing in the development of their own orbital space station once the ISS mission was over. They’re also apparently working on a robotic lunar orbiter and lander mission.

This isn’t the only announcement involving the Deep Space Gateway. It might also get a solar sail. Engineers from the Canadian Space Agency proposed attaching a small solar sail to the Gateway, which could serve in re-orienting the space station without needing propellant. It would have a surface area of about 50-meters, and would save hundreds of kilograms of hydrozine fuel which would normally be used over the lifespan of the Deep Space Gateway. Check out Anatoly Zak’s excellent reporting on this development for the Planetary Society.