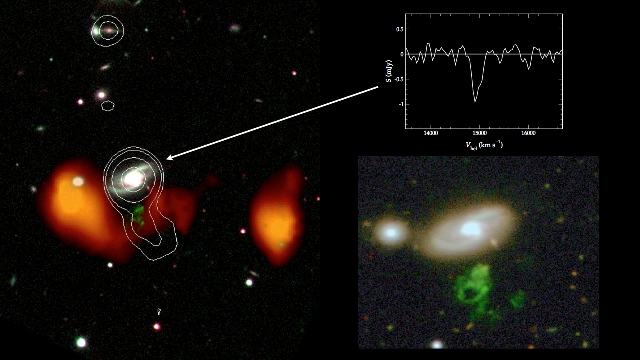

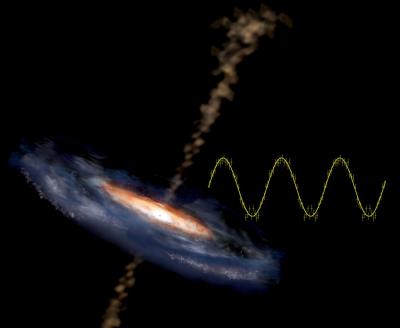

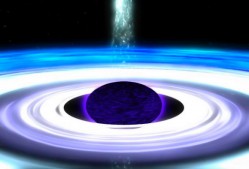

Ever since Hanny Van Arkel found an unusual object while scanning through images as an enthusiastic Galaxy Zoo volunteer, astronomers and astronomy enthusiasts have wondered what the bizarre object, known as “Hanny’s Voorwerp” actually is. Now, new observations made by radio telescopes may have finally revealed the nature of the Voorwerp (Dutch for “object.”) It appears as though a jet of highly energetic particles is being generated by a massive black hole at the center of IC2497, creating an ionized gas cloud.

While surfing through hundred’s of images over a year ago, Hanny, a Dutch school teacher noticed a huge green irregular cloud of gas of galactic scale, located about 60,000 light years from a nearby galaxy, IC2497. The cloud is enormous and the gas is extremely hot (> 15,000 Celsius) but paradoxically it is devoid of stars.

An international team of astronomers, led by Prof. Mike Garrett, and also Hanny van Arkel herself, have observed IC2497 and the Voorwerp with the Westerbork Synthesis Radio Telescope (WSRT) and an e-VLBI array in which the WSRT also participated.

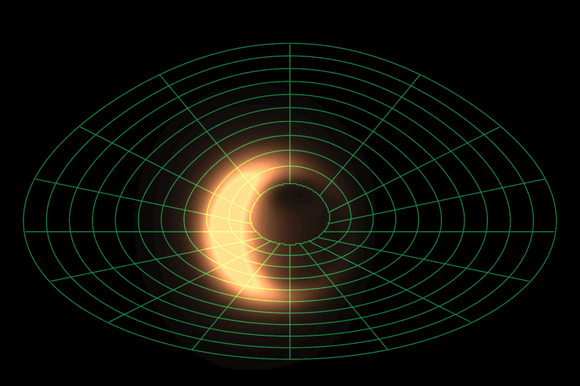

“It looks as though the jet emanating from the black hole clears a path through the dense interstellar medium of IC 2497 towards Hanny’s Voorwerp”, says Garrett. “This cleared channel permits the beam of intense optical and ultraviolet emission associated with the black hole, to illuminate a small part of a large gas cloud that partially surrounds the galaxy. The optical and ultraviolet emission heats and ionizes the gas cloud, thus creating the phenomena known as Hanny’s Voorwerp.”

One remaining question is where does all the hydrogen gas come from? “There is a lot of gas out there – the WSRT observations detect a huge stream of gas that is extended across hundreds of thousands of light years”, says Dr. Gyula Józsa, another member of the team. According to Józsa the total mass of gas is about 5000 million times the mass of the sun. It’s something Dr. Tom Oosterloo thinks he has seen before: “It has all the hallmarks of an interacting system – the gas probably arises from a tidal interaction between IC 2497 and another galaxy, several hundred million years ago.”

Oosterloo also thinks he can identify the culprits, “the stream of gas ends three hundred thousand light years westwards of IC2497 – all the evidence points towards a group of galaxies at the tip of the stream being responsible for this freak cosmic accident”.

Hanny van Arkel, who is visiting the team at ASTRON this week is impressed. “I’m happy we are making progress. Apparently the more we learn about the Voorwerp, the more intriguing it becomes”. Garrett and his team agree – “We think the Voorwerp has a few more secrets to reveal”. The team plan much deeper observations with the WSRT and with other telescopes soon.

Source: ASTRON