The Hubble Space Telescope is going to be used to settle an argument. It’s a conflict between computer models and what astronomers are seeing in a group of stars in 47 Tucanae.

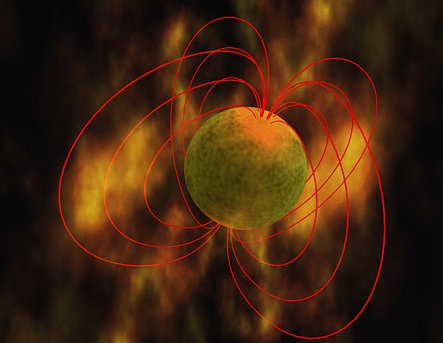

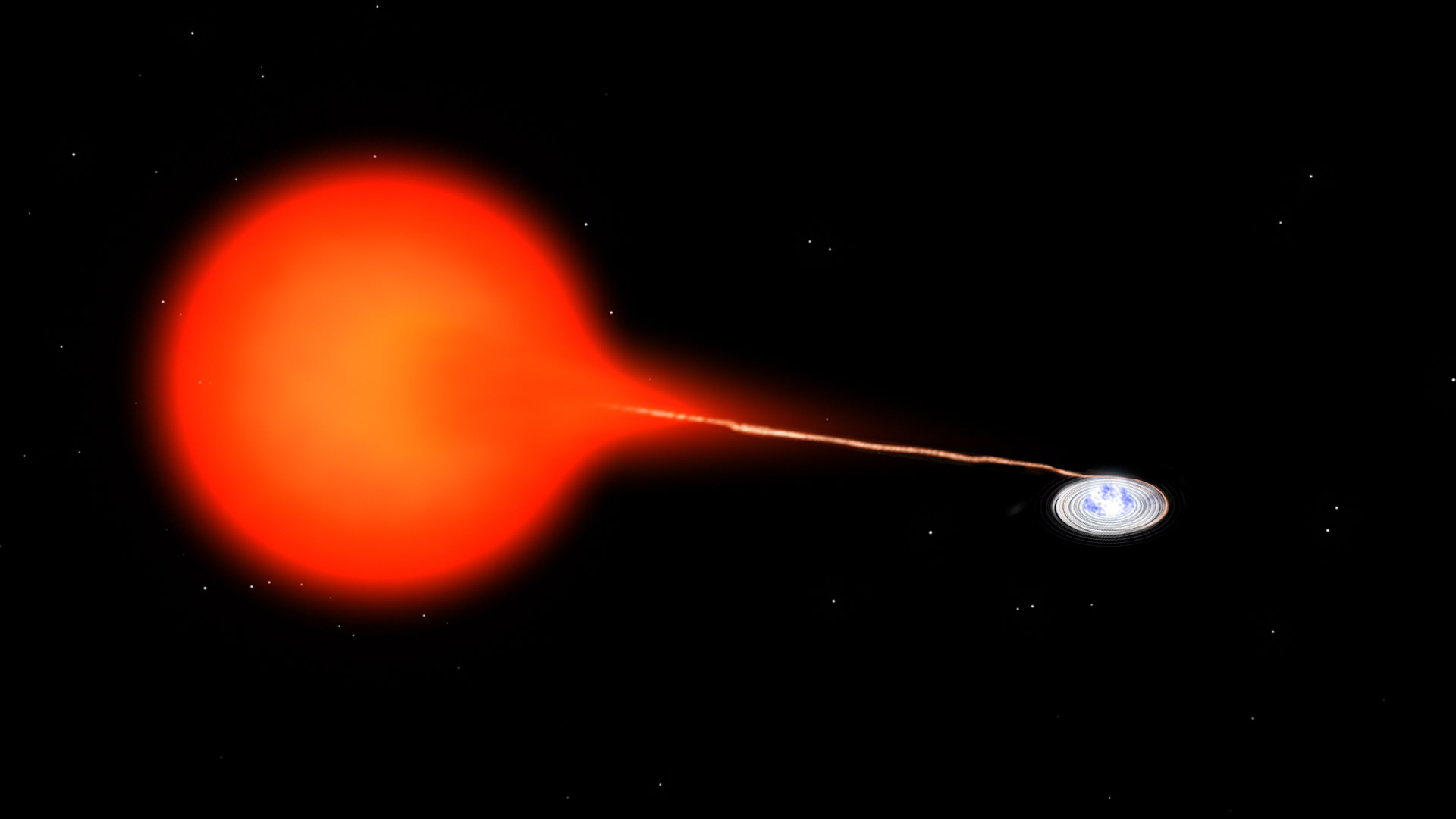

White dwarfs — the dying embers of stars who have burnt off all their fuel — are cooling off slower than expected in this southern globular cluster, according to previous observations with the telescope’s Wide Field Camera and Advanced Camera for Surveys.

Puzzled astronomers are now going to widen that search in 47 Tucanae (which initially focused on a few hundred objects) to 5,000 white dwarfs. They do have some theories as to what might be happening, though.

White dwarfs, stated lead astronomer Ryan Goldsbury from the University of British Columbia, have several factors that chip in to the cooling rate:

– High-energy particle production from the white dwarfs;

– What their cores are made up of;

– What their atmospheres are made up of;

– Processes that bring energy from the core to the surface.

Somewhere, somehow, perhaps one of those factors is off.

This kind of thing is common in science, as astronomers create these programs according to the best educated guesses they can make with respect to the data in front of them. When the two sides don’t jive, they do more observations to refine the model.

“The cause of this difference is not yet understood, but it is clear that there is a discrepancy between the data and the models,” stated the Canadian Astronomical Society (CASCA) and the University of British Columbia in a press release.

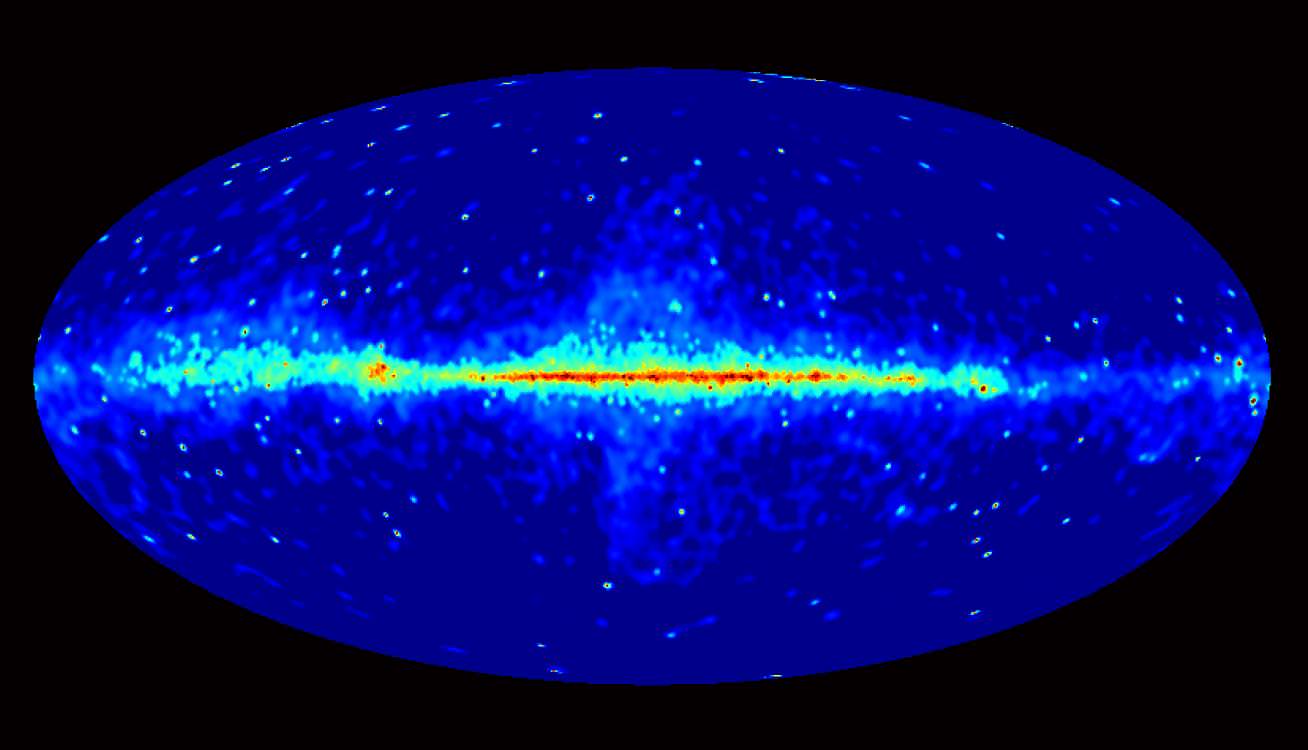

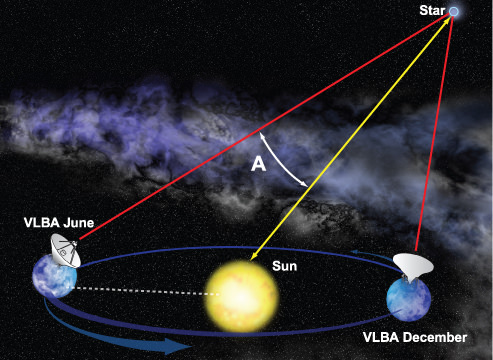

Since the white dwarfs are in a cluster that presumably formed from the same cloud of gas, it allows astronomers to look at a group of stars at a similar distance and to determine the distribution of masses of stars within the cluster.

“Because all of the white dwarfs in their study come from a single well-studied star cluster, both of these bits of information can be independently determined,” the release added.

You can read the entire article on the previous Hubble research on 47 Tucanae at the Astrophysical Journal.

Today’s announcement took place during the annual meeting of CASCA, which is held this year in Vancouver.

Source: CASCA/UBC