When it comes to conspiracy theories and modern preoccupations, few things are more popular than unidentified flying objects (UFOs) and alien abductions. For over half a century, there have been rumors, reports, and urban legends about aliens coming to Earth, dabbling with our genetics, and conducting weird (and often invasive) experiments on our citizens.

And while opinions on what drives this popular phenomenon tend to differ (some say hysteria, others that it is media-driven), a few things are clear. For one, sightings appear to take place far more in the United States than anywhere else in the world. And in recent years, these sightings have been on the rise!

Such are the conclusions of a series of visualizations based on the National UFO Reporting Center (NUFORC). Established in 1974 (and located in Davenport, Washington), the National UFO Reporting Center is “dedicated to the collection and dissemination of objective UFO data”. Since that time, they have been monitoring UFO sightings worldwide and have maintained careful logs about the 104,947 sightings that have taken place since 1905.

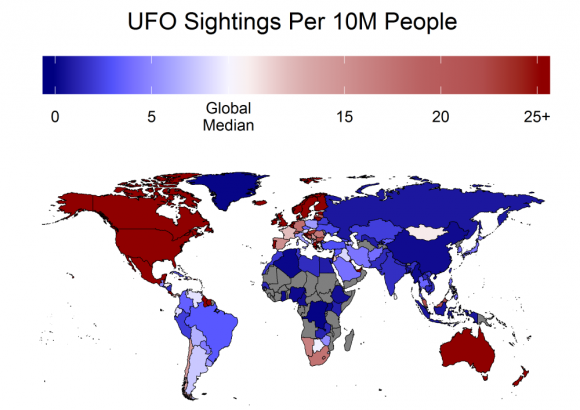

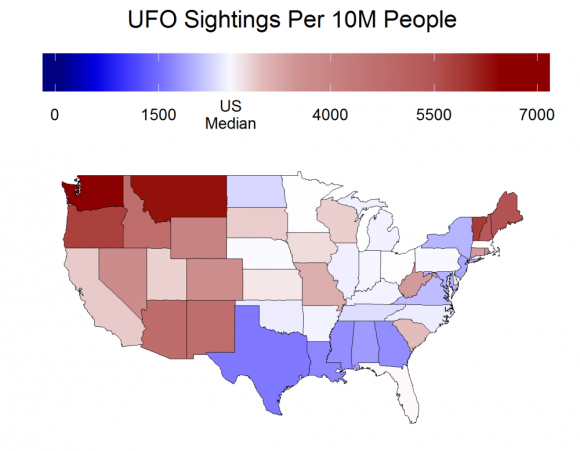

Using this data, Sam Monfort – a Doctoral Candidate from the department of Human Factors & Applied Cognition at George Mason University – produced a series of visuals that illustrate the history of UFO sightings. And based on the visualized trends, some rather interesting conclusions can be drawn. The most obvious is that the geographical distribution of sightings is hardly even. For starters, reports in the USA were equal to about 2500 sightings per 10 million people.

This is almost 300 times higher than the global average. Based on individual states, the concentration of sightings was also quite interesting. Apparently, more sightings happen (per 10 million people) in the West and Northwest, with the highest numbers coming from Washington and Montana. Oregon, Idaho, Arizona and New Mexico also made strong showings, while the Great Lakes and Midwestern states were all consistent with the national median.

On the opposite coast, Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire all had a good number of sightings per capita, though the state of New York even as New York was beneath the national median. Texas actually ranked the lowest, and was followed by the Southern states of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia. But as Monfort told Universe Today via email, this may be slightly skewed because of who is collecting the information:

“[I]t’s worth mentioning that the NUFORC is an American agency (“N” stands for “National”). They make an effort to record international sightings (phone banks staffed 24/7), but I’d guess that sightings in the USA are still over-represented. Honestly, I’d bet that the NUFORC being based in Seattle is the main reason we see so many more sightings in the States. A more thorough analysis might cross-reference sightings from other agencies, like MUFON.”

Canadians did not do much better, coming at second place after the United States with 1000 sightings per 10 million people. And according to a recent article by Allan Maki of The Globe and Mail, its becoming more common – with a record 1982 sightings reported in 2012. He also suggests that this could be due to a combination of growing interest in the subject and reduced stigma.

Iceland, the UK, Australia, the Virgin Islands and Cyprus all ranked a distant third, with between 250 and 500 sightings per 100 million people per year. New Zealand, Mexico, Israel and the Gulf States also produced considerable returns, as did the United Kingdom, Ireland, Portugal, Belgium, Danemark, Finland, Sweden and Norway.

From this distribution, one might make the generalization that more developed nations are more likely to report UFOs (i.e. better record-keeping and all that). And this is a possibility which Monfort explored. In another visualization, he cross-referenced the number of sightings in a respective country with amount of internet access it has (per 100 people), and a limited correlation was shown.

Nations like Israel and the Gulf States have a higher number of sightings than neighboring countries like Syria, Saudi Arabia and Iraq, while South Africa has more reported sightings than several North African and Sub-Saharan African nations surveyed. However, fast-developing nations like Russia, China and India showed a lower than average level of sightings, while Guyana and Suriname showed a higher than average level.

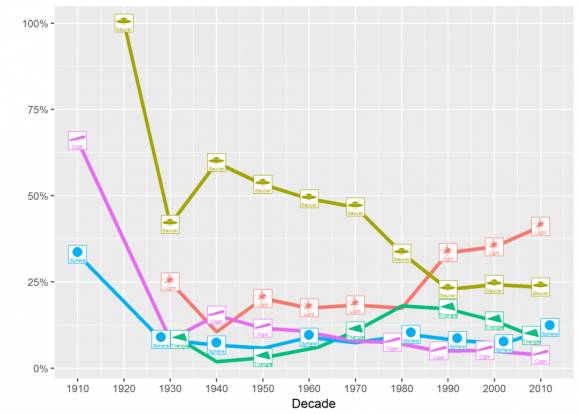

France, Italy and the Czech Republic also lagged behind many of their European counterparts, and Germany and Spain were only slightly higher than the average. So much like distribution by state within the US, internet access does not seem to be a consistent determining factor. Another interesting visualization was the one which broke down the sightings per decade based on the nature of the sighting.

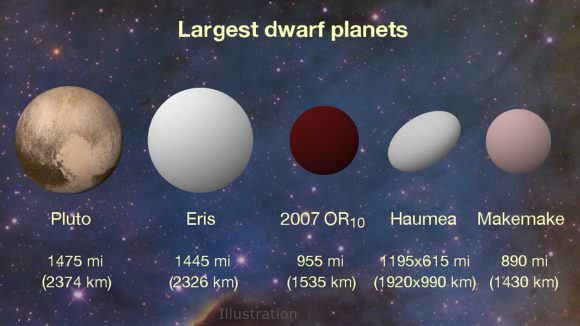

As you can see from the table above, when UFO sightings first began in the early 20th century, they reportedly took the form of either a sphere or a cigar-shaped object. This differs from the 1920s, when “flying saucers” began to appear, and remained the dominant trend throughout World War II and the Cold War era. And ever since the 1990s – what Monfort refers to as “post-internet” era – the most common UFO sightings took the form of bright lights.

“If I had to guess, I’d say it was a combination of factors,” said Monfort. “Like I mentioned in the blog, it seems a lot more plausible that someone would see strange lights in the sky than a flying object with a concrete shape (like a saucer). Seeing a shape implies that the object is pretty close to you, “and if it’s that close why didn’t you take a video of it?”

As for other factors, Monfort considers the possibility of fireworks and (as one comment on his blog suggested) Chinese lanterns. “Those are the little paper balloons you light a candle in and let fly. Some of the bright light sightings could be those, especially since I’d bet most Chinese lanterns are released in groups, with several people going out in groups to release them together. (Often people report formations of lights.)”

Further Reading: Visualize This