About 14,500 years ago, Earth began transitioning from its cold, glacial self to a warmer interglacial state. However, partway through this period, temperatures suddenly returned to near-glacial conditions. This abrupt change (known as the Younger Dryas period) is believed by some to be the reason why hunter-gatherers started forming sedentary communities, farming, and laying the groundwork for civilization as we know it – aka. the Neolithic Revolution.

For over a decade, there have been scientists who have argued that this period was the result of a comet hitting Earth. Known as the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis (aka. the Clovis Comet Hypothesis), the theory is largely based on ice core samples from Greenland that show a sudden global temperature change. But according to a new study by a research team from the University of Edinburgh, archaeological evidence may also prove this hypothesis correct.

The Younger Dryas period takes its name from a species of flower known as Dryas octopetala. This plant is known to grow in cold conditions, and became common in Europe during the period. Because of the way it began abruptly – roughly 12,500 years ago – and then ended just as abruptly 1200 years later, many scientists are convinced it was caused by an external event.

For the sake of their study – which was recently published in the journal Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry under the title “Decoding Göbekli Tepe With Archaeoastronomy: What Does the Fox Say?“- the team found an astronomical link to the stone pillars at Göbekli Tepe. Located in southern Turkey, this archaeological find is the oldest known temple site in the world (dated to ca. 10,950 BCE).

This site, it should be noted, is contemporary with the Greenland ice core samples, which are dated to around 10,890 BCE. Of the sites many features, none are more famous than the many standing pillars that dot the excavated grounds. This is because of the extensive pictograms and animal reliefs that decorate these pillars, which include various representations of mammal and avian species- particularly vultures.

Pillar 43, which is also known as the “vulture stone”, was of particular interest to archeologists, as it is suspected that its representations (associated with death) could have been intended to commemorate a devastating event. The other images, they ventured, were meant to depict the constellations, and that their placement relative to each other accorded to the positions of the then-known asterisms in the night sky.

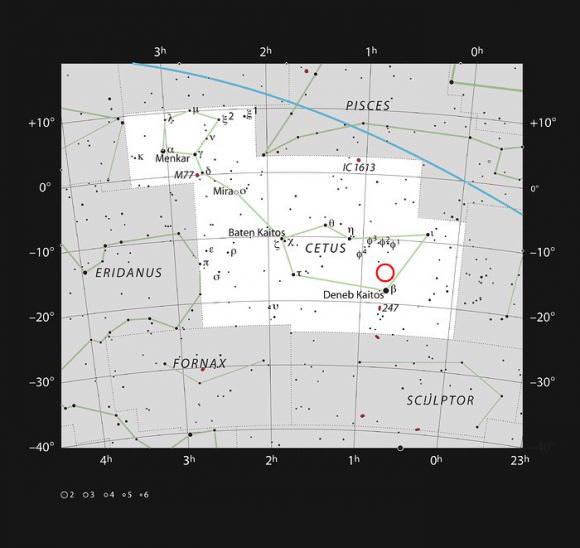

This theory was based on images they took of the site, which they then examined using the planetarium program stellarium 0.15. In the end, they found that the images bore a resemblance to constellations that would have been visible in 10,950 BCE. As such, they concluded that the temple site may have been an observatory, and that the images were a catalog of celestial events – which include the Taurid meteor stream.

As they state in their study:

“We begin by noting the carving of a scorpion on pillar 43, a well -known zodiacal symbol for Scorpius. Based on this observation, we investigate to what extent other symbols on pillar 43 can be interpreted as zodiacal symbols or other familiar astronomical symbols… We suggest the vulture/eagle on pillar 43 can be interpreted as the ‘teapot’ asterism of our present-day notion of Sagittarius; the angle between the eagle/vulture’s head and wings, in particular, agrees well with the ‘handle’,‘lid’ and ‘spout’ of the teapot asterism. We also suggest the ‘bent-bird’ with downward wriggling snake or fish can be interpreted as the ‘13th sign of the zodiac’, i.e. of our present-day notion of Ophiuchus. Although its relative position is not very accurate, we suggest the artist(s) of pillar 43 were constrained by the shape of the pillar. These symbols are a reasonably good match with their corresponding asterisms, and they all appear to be in approximately the correct relative locations.

Of course, the team fully acknowledges that an astronomical interpretation is by no means the only possibility. In addition to the possibility of them being mythological references, they could also be representations of hunting or migration patterns. It’s also entirely possible they were not meant to convey any specific meaning, and were merely a description of the local environment, which would have been rich in flora and fauna at the time.

In addition, the way vultures are commonly featured could be an indication that the site was a burial ground. This is consistent with iconography found at the archaeological sites of Çatalhöyük (in central, southern Turkey) and Jericho (in the West Bank). During the time period in question, Neolithic peoples were known to conduct sky burials, where the bodies of the deceased were left out in the open for carrion birds to pick over.

In such practices, the head was sometimes removed from the deceased and kept (for the sake of ancestor worship). This is consistent with one of the characters on Pillar 43, which appears to be a headless human. However, as the team go on to explain, they are confident that the connection between the site’s images and the Taurid meteor stream is a plausible one.

“[O]ur basic statistical analysis indicates our astronomical interpretation is very likely to be correct,” they write. “We are therefore content to limit ourselves to this hypothesis, and logically we are not required to pursue others.” And of course, they acknowledge that further research will be necessary before any conclusions can be made.

Further Reading: MAA Journal