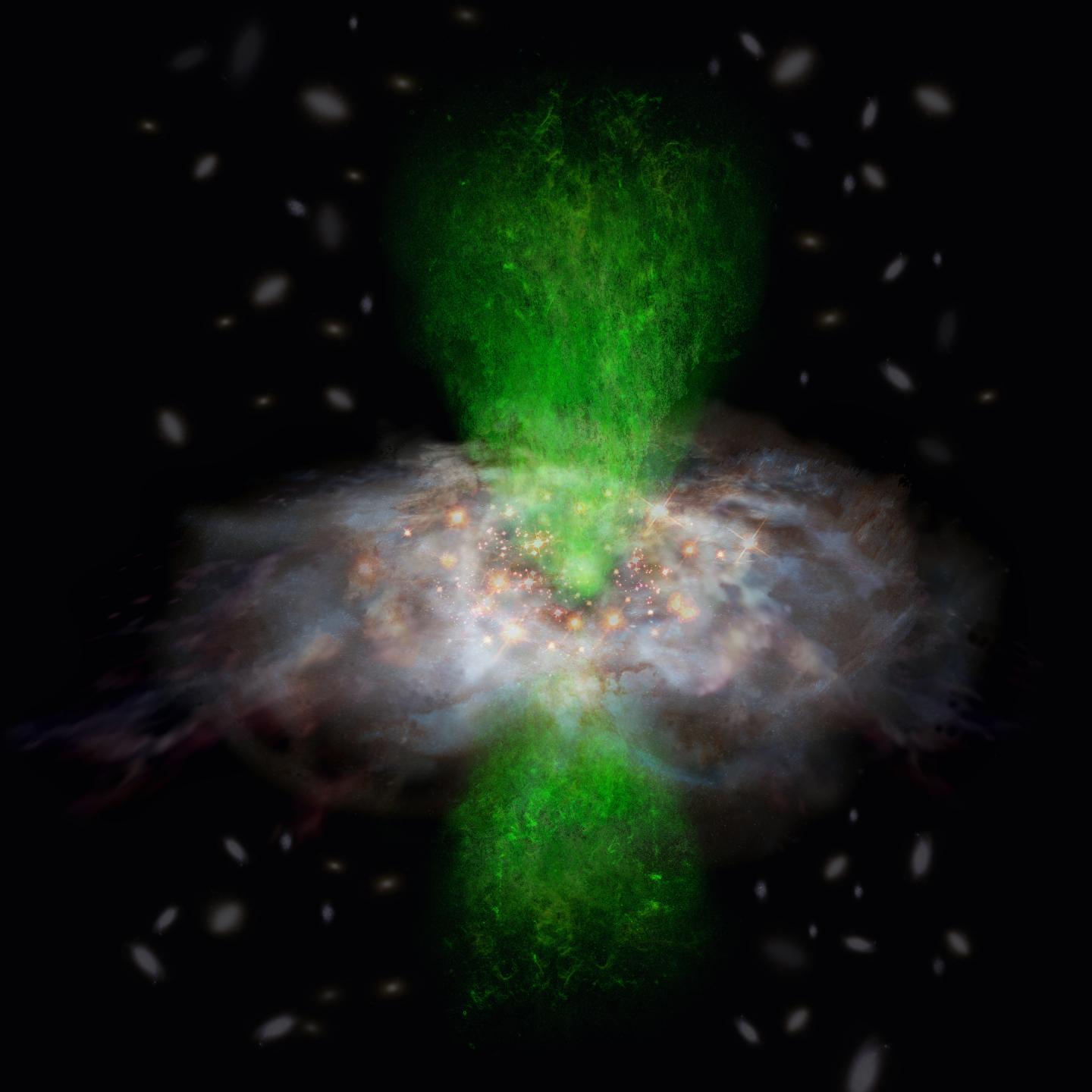

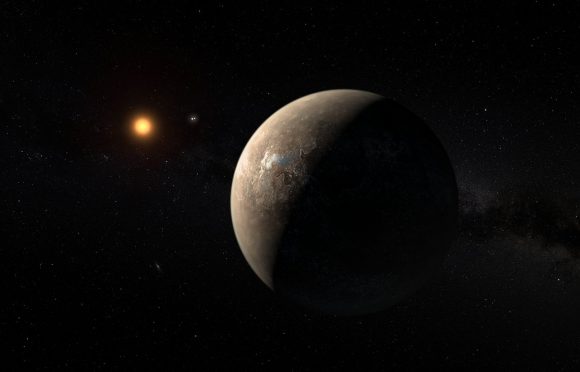

Since it’s discovery was announced in August of 2016, Proxima b has been an endless source of wonder and the target of many scientific studies. As the closest extra-solar planet to our Solar System – and a terrestrial planet that orbits within Proxima Centauri’s circumstellar habitable zone (aka. “Goldilocks Zone”) – scientists have naturally wondered whether or not this planet could be habitable.

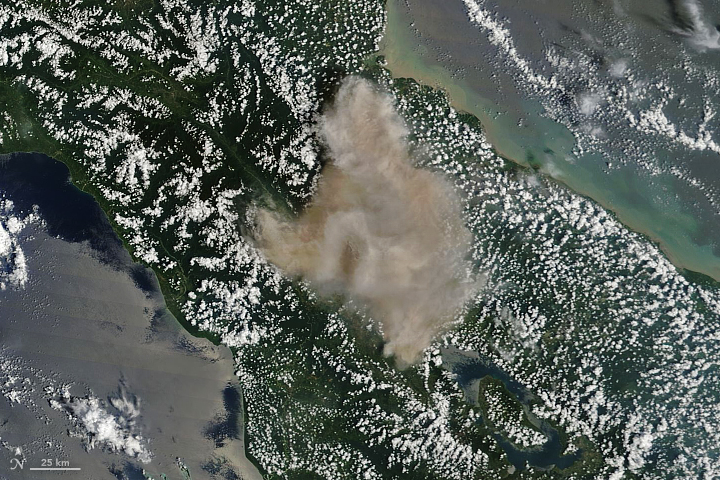

Unfortunately, many of these studies have emphasized the challenges that life on Proxima b would likely face, not the least of which is harmful radiation from its star. According to a recent study, a team of astronomers used the ALMA Observatory to detect a large flare emanating from Proxima Centauri. This latest findings, more than anything, raises questions about how habitable its exoplanet could be.

The study, titled “Detection of a Millimeter Flare from Proxima Centauri“, recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Led by Meredith A. MacGregor, an NSF Astronomy and Astrophysics Postdoctoral Fellow at the Carnegie Institution for Science, the team also included members from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) and the University of Colorado Boulder.

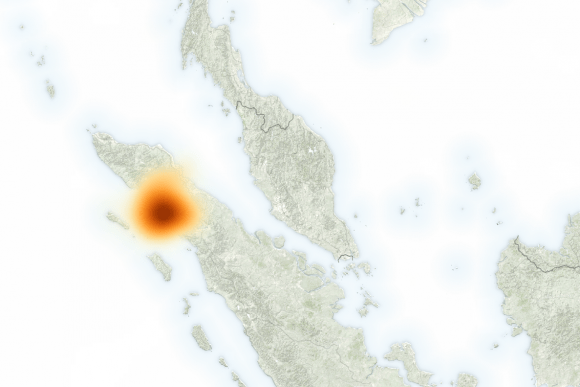

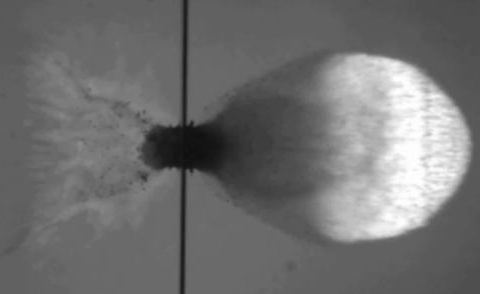

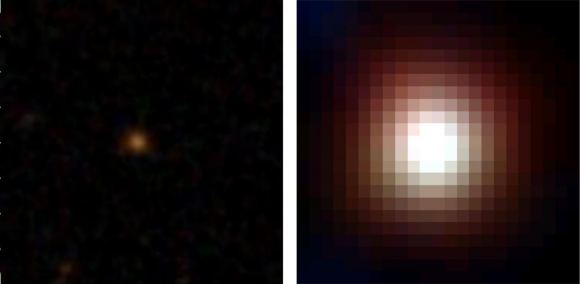

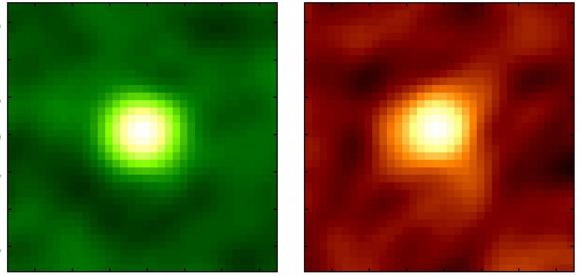

For the sake of their study, the team used data obtained by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) between January 21st to April 25th, 2017. This data revealed that the star underwent a significant flaring event on March 24th, where it reached a peak that was 1000 times brighter than the star’s quiescent emission for a period of ten seconds.

Astronomers have known for a long time that when compared to stars like our Sun, M-type stars are variable and unstable. While they are the smallest, coolest, and dimmest stars in our Universe, they tend to flare up at a far greater rate. In this case, the flare detected by the team was ten times larger than our Sun’s brightest flares at similar wavelengths.

Along with a smaller preceding flare, the entire event lasted fewer than two minutes of the 10 hours that ALMA was observing the star between January and March of last year. While it was already known that Proxima Centauri, like all M-type stars, experiences regular flare activity, this one appeared to be a rare event. However, stars like Proxima Centauri are also known to experienced regular, although smaller, X-ray flares.

All of this adds up to a bad case for habitability. As MacGregor explained in a recent NRAO press statement:

“It’s likely that Proxima b was blasted by high energy radiation during this flare. Over the billions of years since Proxima b formed, flares like this one could have evaporated any atmosphere or ocean and sterilized the surface, suggesting that habitability may involve more than just being the right distance from the host star to have liquid water.”

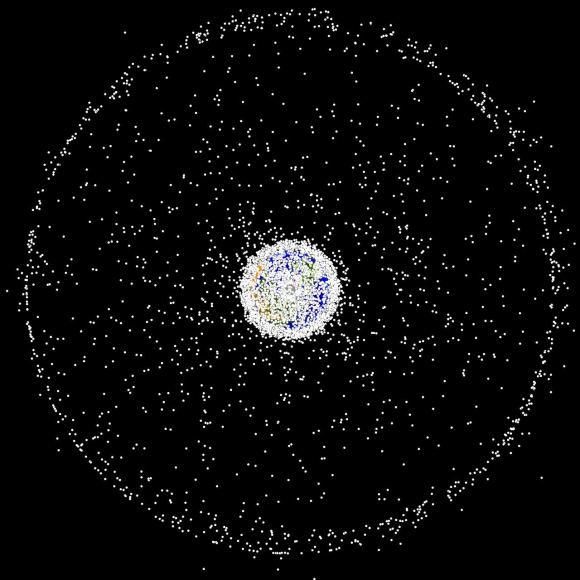

MacGregor and her colleagues also considered the possibility that Proxima Centauri is circled by several disks of dust. This was suggested by a previous study (also based on ALMA data) that indicated that the light output of both the star and flare together pointed towards the existence of debris belts around the star. However, after examining the ALMA data as a function of observing time, they were able to eliminate this as a possibility.

As Alycia J. Weinberger, also a researcher with the Carnegie Institution for Science and a co-author on the paper, explained:

“There is now no reason to think that there is a substantial amount of dust around Proxima Cen. Nor is there any information yet that indicates the star has a rich planetary system like ours.”

To date, studies that have looked at possible conditions on Proxima b have come to different conclusions as to whether or not it could retain an atmosphere or liquid water on its surface. While some have found room for “transient habitability” or evidence of liquid water, others have expressed doubt based on the long-term effects that radiation and flares from its star would have on a tidally-locked planet.

In the future, the deployment of next-generation instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope are expected to provide more detailed information on this system. With precise measurements of this star and its planet, the question of whether or not life can (and does) exist in this system may finally be answered.

And be sure to enjoy this animation of Proxima Centauri in motion, courtesy of NRAO outreach:

Further Reading: NRAO, The Astrophysical Journal Letters