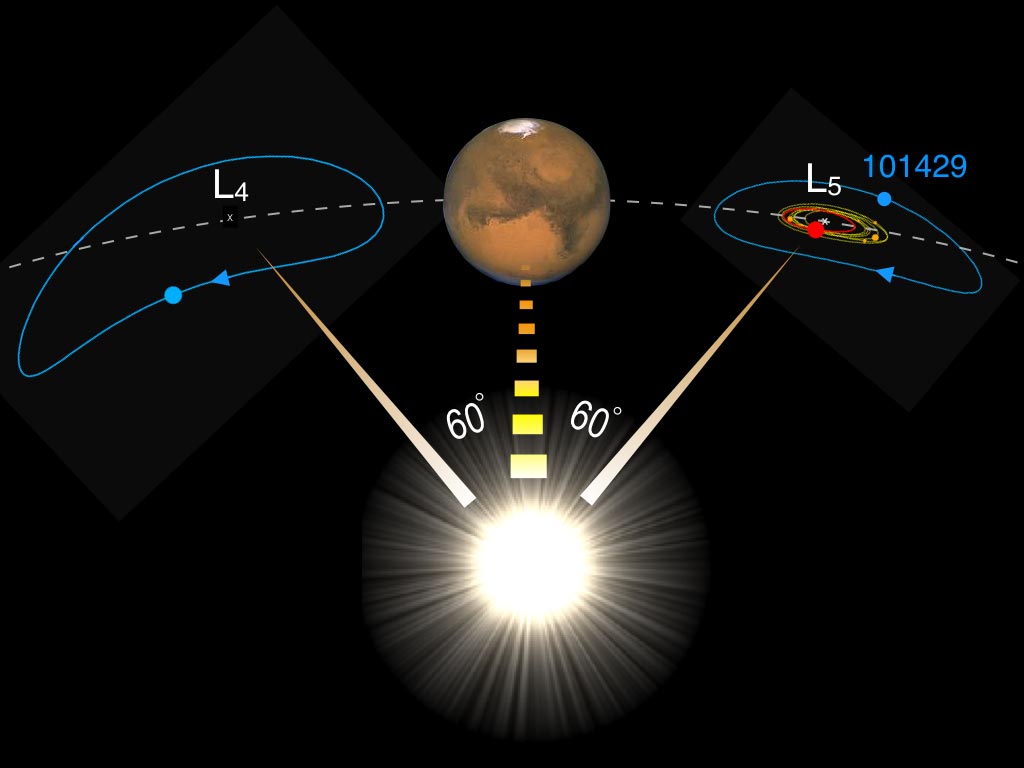

Although Mars is much smaller than Earth, it has two moons. Deimos and Phobos were probably once asteroids that were captured by the gravity of Mars. The red planet has also captured nine other small bodies. These asteroids don’t orbit Mars directly, but instead, orbit gravitationally stable points on either side of the planet known as Lagrange points. They are known as trojans, and they move along the Martian orbit about 60° ahead or behind Mars. Most of these trojans seem to be of Martian origin and formed from asteroid impacts with Mars. But one of the trojans seems to have a different origin.

Continue reading “One Mars Trojan asteroid has the same chemical signature as the Earth’s moon”Even older red dwarf stars are pumping out a surprising amount of deadly radiation at their planets

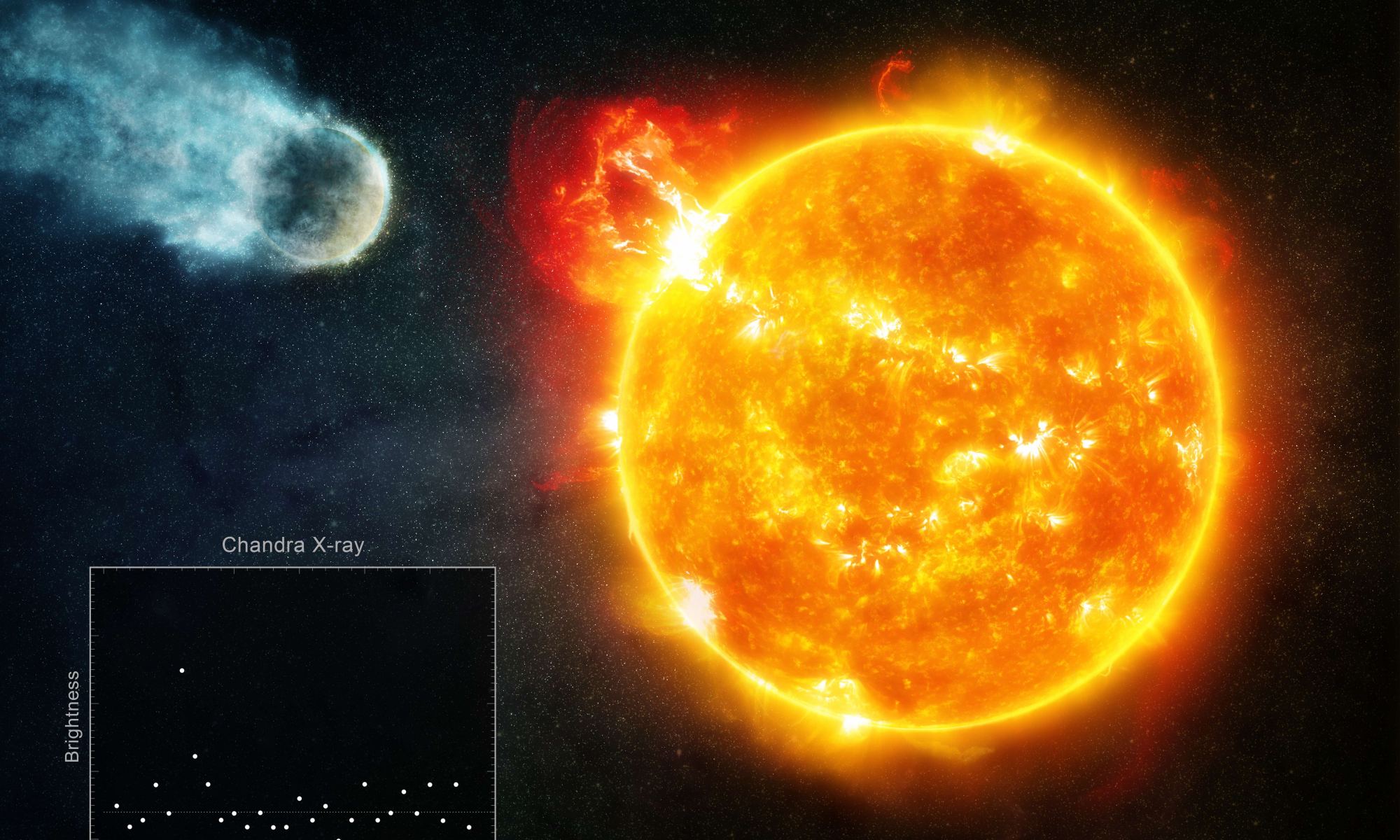

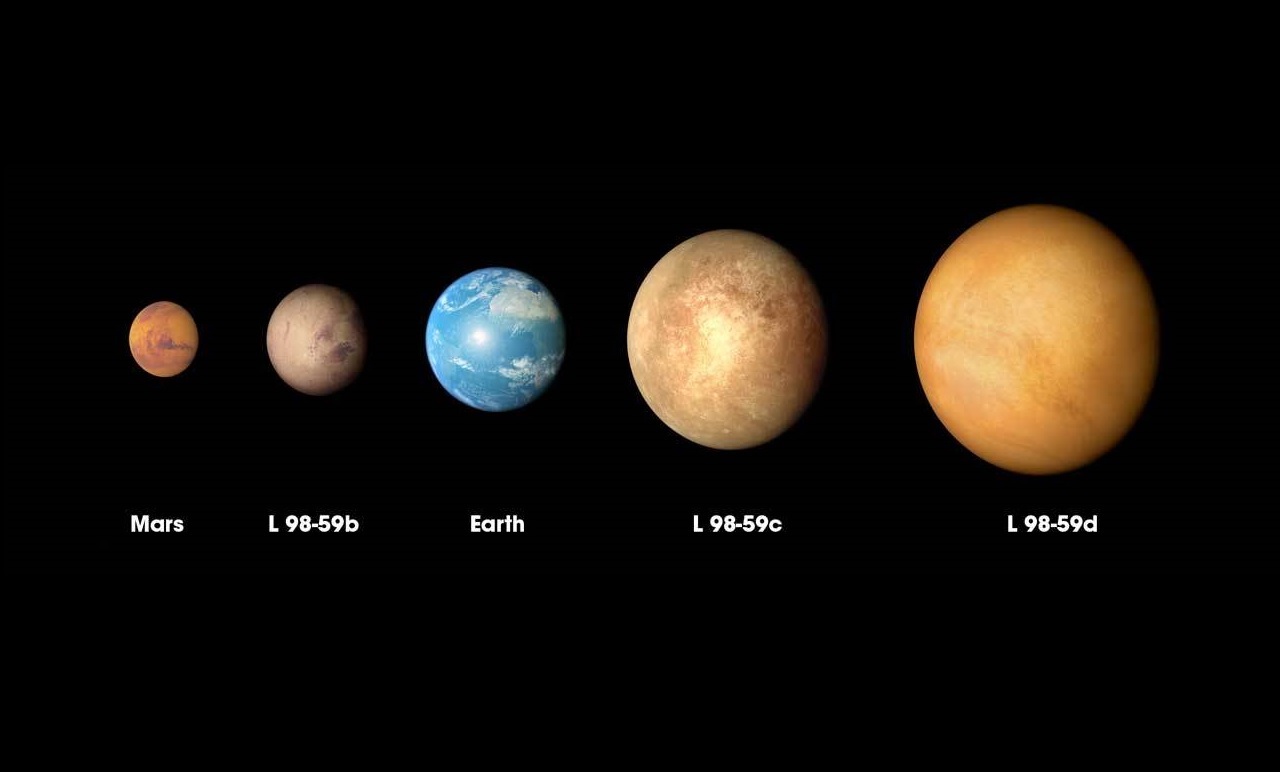

Most of the potentially habitable exoplanets we’ve discovered orbit small red dwarf stars. Red dwarfs make up about 75% of the stars in our galaxy. Only about 7.5% of stars are g-type like our Sun. As we look for life on other worlds, red dwarfs would seem to be their most likely home. But red dwarfs pose a serious problem for habitable worlds.

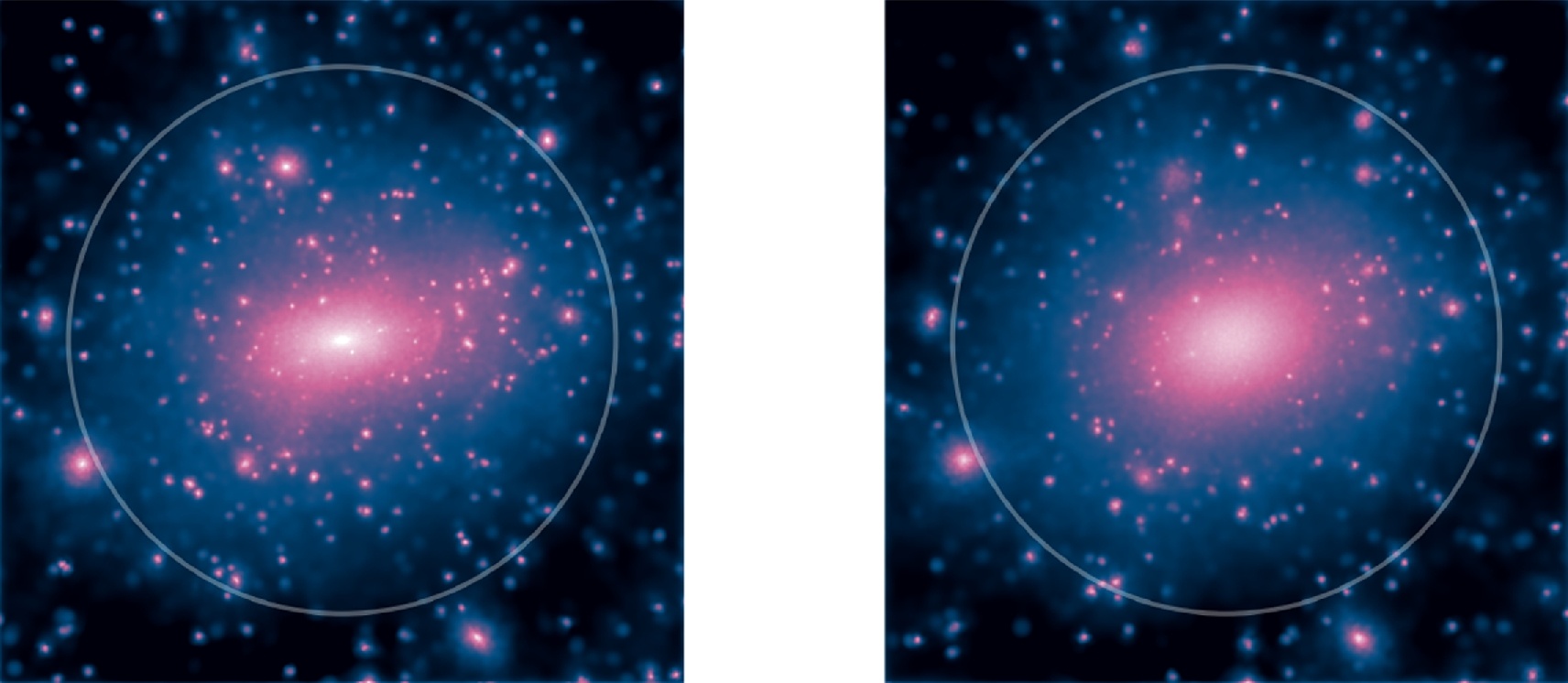

Continue reading “Even older red dwarf stars are pumping out a surprising amount of deadly radiation at their planets”Something other than just gravity is contributing to the shape of dark matter halos

It now seems clear that dark matter interacts more than just gravitationally. Earlier studies have hinted at this, and a new study supports the idea even further. What’s interesting about this latest work is that it studies dark matter interactions through entropy.

Continue reading “Something other than just gravity is contributing to the shape of dark matter halos”New Receiver Will Boost Interplanetary Communication

If humans want to travel about the solar system, they’ll need to be able to communicate. As we look forward to crewed missions to the Moon and Mars, communication technology will pose a challenge we haven’t faced since the 1970s.

Continue reading “New Receiver Will Boost Interplanetary Communication”We use the Transit Method to Find other Planets. Which Extraterrestrial Civilizations Could use the Transit Method to Find Earth?

We have discovered more than 4,000 planets orbiting distant stars. They are a diverse group, from hot Jupiters that orbit red dwarf stars in a few days to rocky Earth-like worlds that orbit Sun-like stars. With spacecraft such as Gaia and TESS, that number will rise quickly, perhaps someday leading to the discovery of a world where intelligent life might thrive. But if we can discover alien worlds, life on other planets could find us. Not every nearby star would have a good view of our world, but some of them would. New work in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society tries to determine which ones.

Continue reading “We use the Transit Method to Find other Planets. Which Extraterrestrial Civilizations Could use the Transit Method to Find Earth?”We actually don’t know how fast the Milky Way’s supermassive black hole is spinning but there might be a way to find out

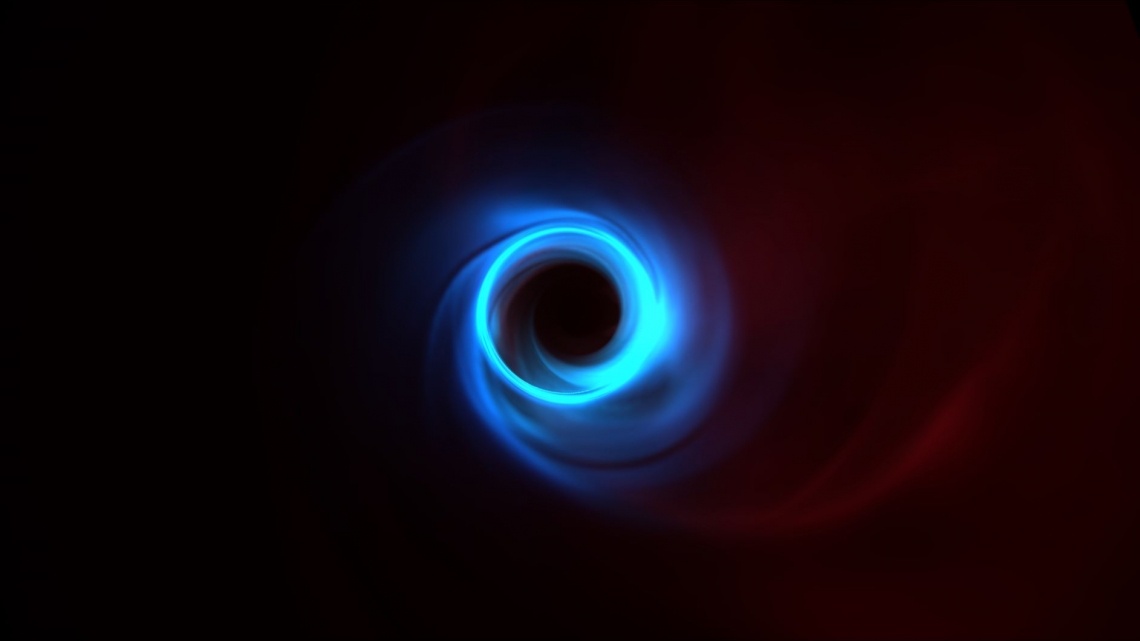

Unless Einstein is wrong, a black hole is defined by three properties: mass, spin, and electric charge. The charge of a black hole should be nearly zero since the matter captured by a black hole is electrically neutral. The mass of a black hole determines the size of its event horizon, and can be measured in several ways, from the brightness of the material around it to the orbital motion of nearby stars. The spin of a black hole is much more difficult to study.

Continue reading “We actually don’t know how fast the Milky Way’s supermassive black hole is spinning but there might be a way to find out”Astronomers Watch a Star Get Spaghettified by a Black Hole

The gravitational dance between massive bodies, tidal forces occur because the pull of gravity from an object depends upon your distance from it. So, for example, the side of Earth near the Moon is pulled a bit more than the side opposite the Moon. As a result, the Earth stretches and flattens a bit. On Earth, this effect is subtle but strong enough to give the oceans high and low tides. Near a black hole, however, tidal forces can be much stronger, creating an effect known as spaghettification.

Continue reading “Astronomers Watch a Star Get Spaghettified by a Black Hole”Black Holes Make Complex Gravitational-Wave Chirps as They Merge

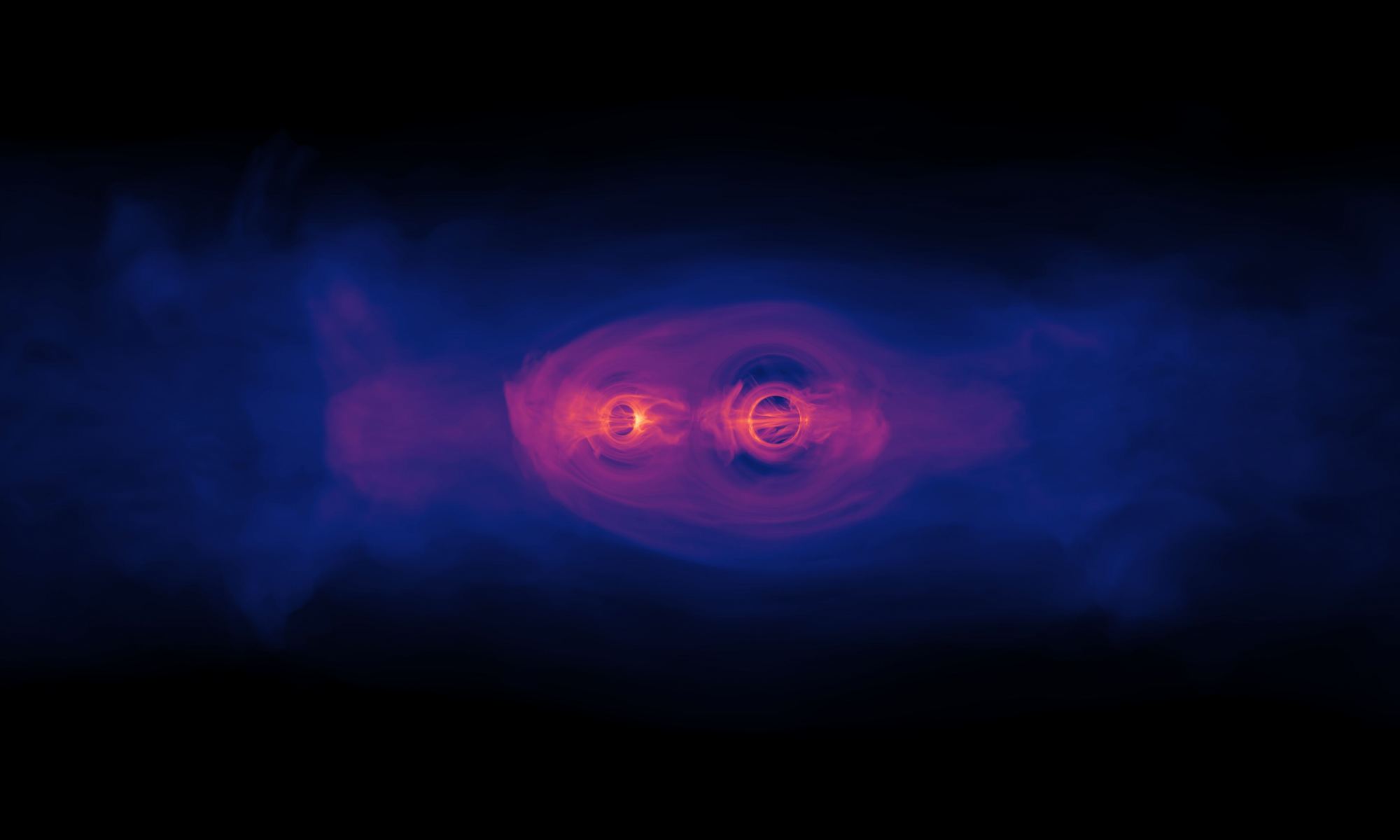

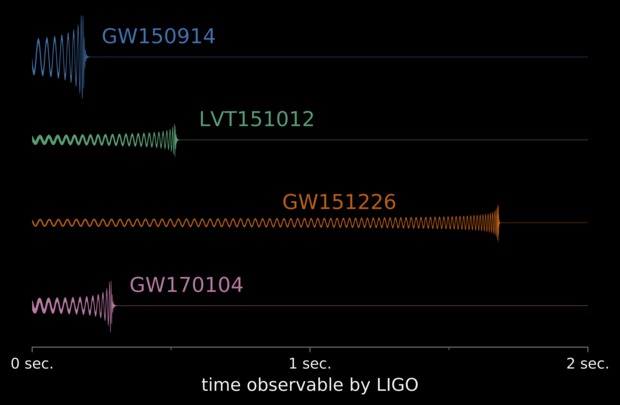

Gravitational waves are produced by all moving masses, from the Earth’s wobble around the Sun to your motion as you go about your daily life. But at the moment, those gravitational waves are too small to be observed. Gravitational observatories such as LIGO and VIRGO can only see the strong gravitational waves produced by merging stellar-mass black holes.

Gravitational-Wave Lensing is Possible, but it’s Going to be Incredibly Difficult to Detect

Gravity is a strange thing. In our everyday lives, we think of it as a force. It pulls us to the Earth and holds planets in orbits around their stars. But gravity isn’t a force. It is a warping of space and time that bends the trajectory of objects. Throw a ball in deep space, and it moves in a straight line following Newton’s First Law of Motion. Throw the same ball near the Earth’s surface, and it follows a parabolic trajectory caused by Earth’s warping of spacetime around it.

Continue reading “Gravitational-Wave Lensing is Possible, but it’s Going to be Incredibly Difficult to Detect”Einstein. Right again

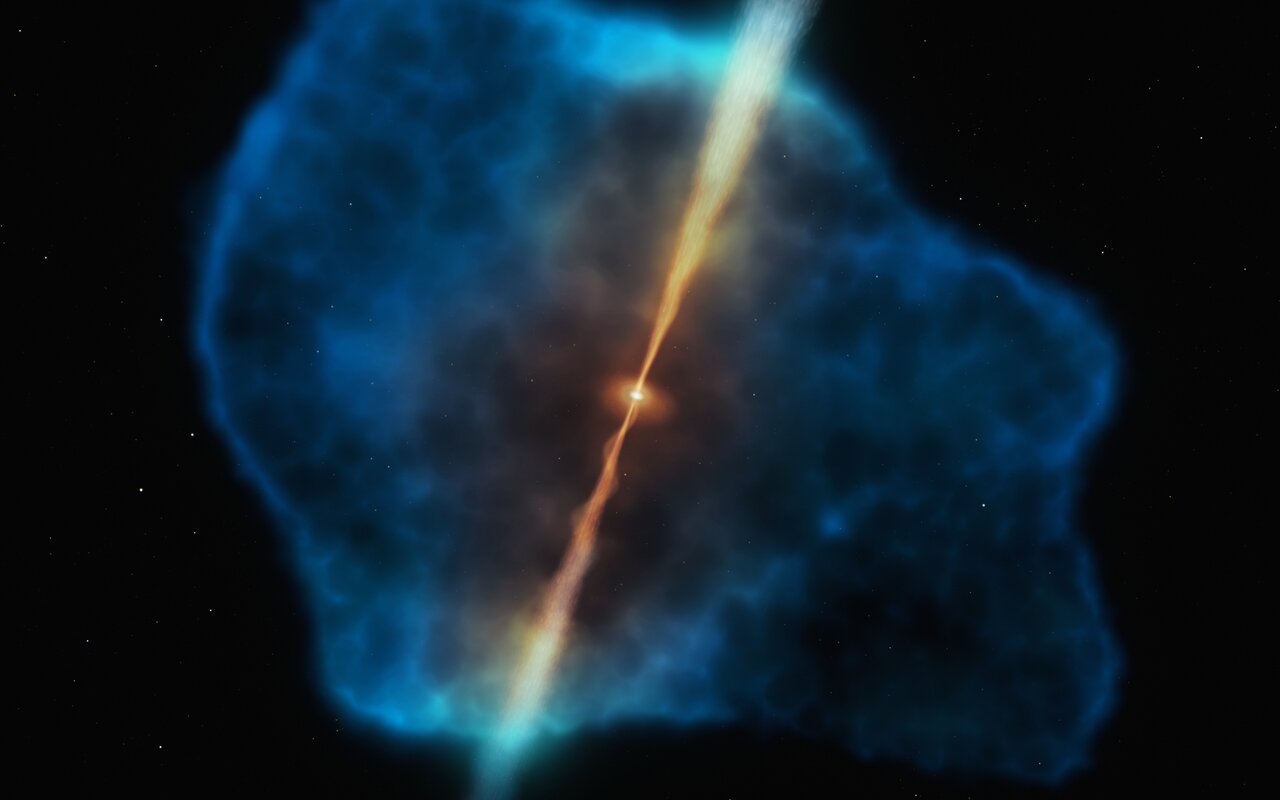

Most of what we know about black holes is based upon indirect evidence. General relativity predicts the structure of a black hole and how matter moves around it, and computer simulations based on relativity are compared with what we observe, from the accretion disks that swirl around a black hole to the immense jets of material they cast off at relativistic speeds. Then in 2019, radio astronomers captured the first direct image of the supermassive black hole in M87. This allows us to test the limits of relativity in a new and exciting way.

Continue reading “Einstein. Right again”