Astronomers want to collect as much data as possible using as many systems as possible. Sometimes that requires coordination between instruments. The teams that run the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the upcoming Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey (Ariel) missions will have plenty of opportunity for that once both telescopes are online in the early 2030s. A new paper, available in pre-print on arXiv, from the Ariel-JWST Synergy Working Group details just how exactly the two systems can work together to better analyze exoplanets.

JWST has already been at the center of media attention since even before its launch in late 2021. It is currently the most capable of our space-based observatories, but it is a multi-purpose tool that has a long line of scientists waiting to get time on it. Capable of observing everything from far-away black holes to interstellar comets passing through our own solar system, JWST has absurdly high resolution but lacks the sheer amount of time it takes to observe some exoplanets fully. In addition, in some cases its too sensitive, as exceptionally bright stars, which are great for observing exoplanet atmospheres, are powerful enough to saturate the detectors on JWST, making it useless to track exoplanets orbiting those types of stars.

Ariel, on the other hand, is specifically being designed with large-scale surveys in mind. It doesn’t have the resolution of JWST, but instead takes a more “dragnet” approach to observations. It will watch thousands of stars with exoplanets over long periods of time, at relatively low resolutions, something that JWST isn’t capable of due to other priorities for its extremely high-resolution capabilities. It also has a single detection instrument that can capture a broad spectrum of wavelengths all at once, whereas JWST requires separate instruments to cover different ranges. To be clear, Ariel has nowhere near the resolution of JWST, and an aperture around 1/6th the size of its larger cousin. But it’s also an “M-Class” mission for ESA, which means that its both budget and scope limited, whereas JWST famously blew its budget multiple times.

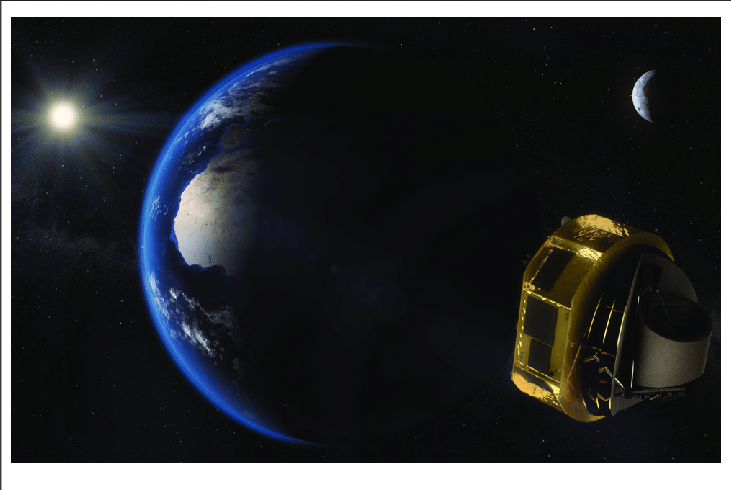

Video describing the Ariel mission. Credit - Ariel Space Mission YouTube ChannelIn the paper, the authors note that there are definitely areas where the two telescopes will align with their objectives. One of the most notable is their position - they will both be placed at the L2 Earth-Sun Lagrange point, giving them a common frame of reference not available to most other telescopes. While JWST can be thought of as a “sniper” that must target individual systems or planets, Ariel can be thought of as a survey, where it broadly watches whole swathes of the sky for long periods.

Synergies go both ways with the two telescope’s specialties. According to the paper, there are several data flows that will utilize each mission’s strengths, and some where the combination of both will help them overcome the limitations of either as a stand-alone project. For example, JWST can look at individual atmospheres of exoplanets, and pass that information along to Ariel which can compare the specific planet JWST is looking at to see how it fits in with thousands of other planets.

Alternatively, Ariel can survey 1,000 planets, and find something weird in one of them. Passing that info over to JWST would allow the much higher resolution telescope to focus on that one outlier for long enough to answer questions that Ariel alone wouldn’t be able to. Assuming the JWST operators prioritize that particular campaign highly enough anyway.

Fraser’s update on what JWST has discovered so far.As mentioned above, Ariel is actually better placed to analyze bright stars that would saturate JWST’s detectors. On the other hand, JWST is capable of finding much fainter, harder to detect targets that Ariel simply can’t see with its resolution. The wavelength coverage between the two missions synergizes as well. Ariel can capture a large part of the infrared spectrum with a single exposure, but JWST can see even further into it with its MIRI instrument. So rather than relying on multiple sensors on the JWST itself, Ariel could combine its readings with MIRI’s to make a complete infrared picture without requiring more of JWST’s time.

It will be a while before this collaboration gets off the ground, though. Ariel is expected to launch in 2029, with science operations to begin fully in 2030, with a 4 year operational window planned after that. Though JWST’s primary scientific mission is planned to end in July 2027, it has enough fuel to maintain orbit until the 2040s. So unless something goes catastrophically wrong with either of them, we should have at least 10 years of collaboration between the world’s most powerful space telescope and its focused, functional exoplanet observing cousin.

Learn More:

Q. Changeat et al. - On the synergetic use of Ariel and JWST for exoplanet atmospheric science

UT - ESA's Ariel Mission is Approved to Begin Construction

UT - The Most Compelling Places to Search for Life Will Look Like "Anomalies"

UT - ESA's ARIEL Mission Will Study the Atmospheres of More Than 1,000 Exoplanets

Universe Today

Universe Today