Four years ago, astronomers spotted a distant supermassive black hole swallowing an entire star. The star had wandered to close to the SMBH, and the black hole's powerful gravity prevented its escape. It was a tidal disruption event (TDE), and now, four years later, the energy output from the TDE is still rising.

The TDE is named AT2018hyz, where AT stands for Astronomical Transient, 2018 is the year of initial discovery, and hyz is a sequential designation code for the year. It was initially spotted by the All Sky Automated Survey for SuperNovae (ASASS-SN) in 2018, but the radio emissions only appeared and were detected in 2022.

The observations showing the continuing rise in energy emissions are in new research in The Astrophysical Journal. It's titled "Continued Rapid Radio Brightening of the Tidal Disruption Event AT2018hyz," and the lead author is Yvette Cendes. Cendes is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Physics at the University of Oregon.

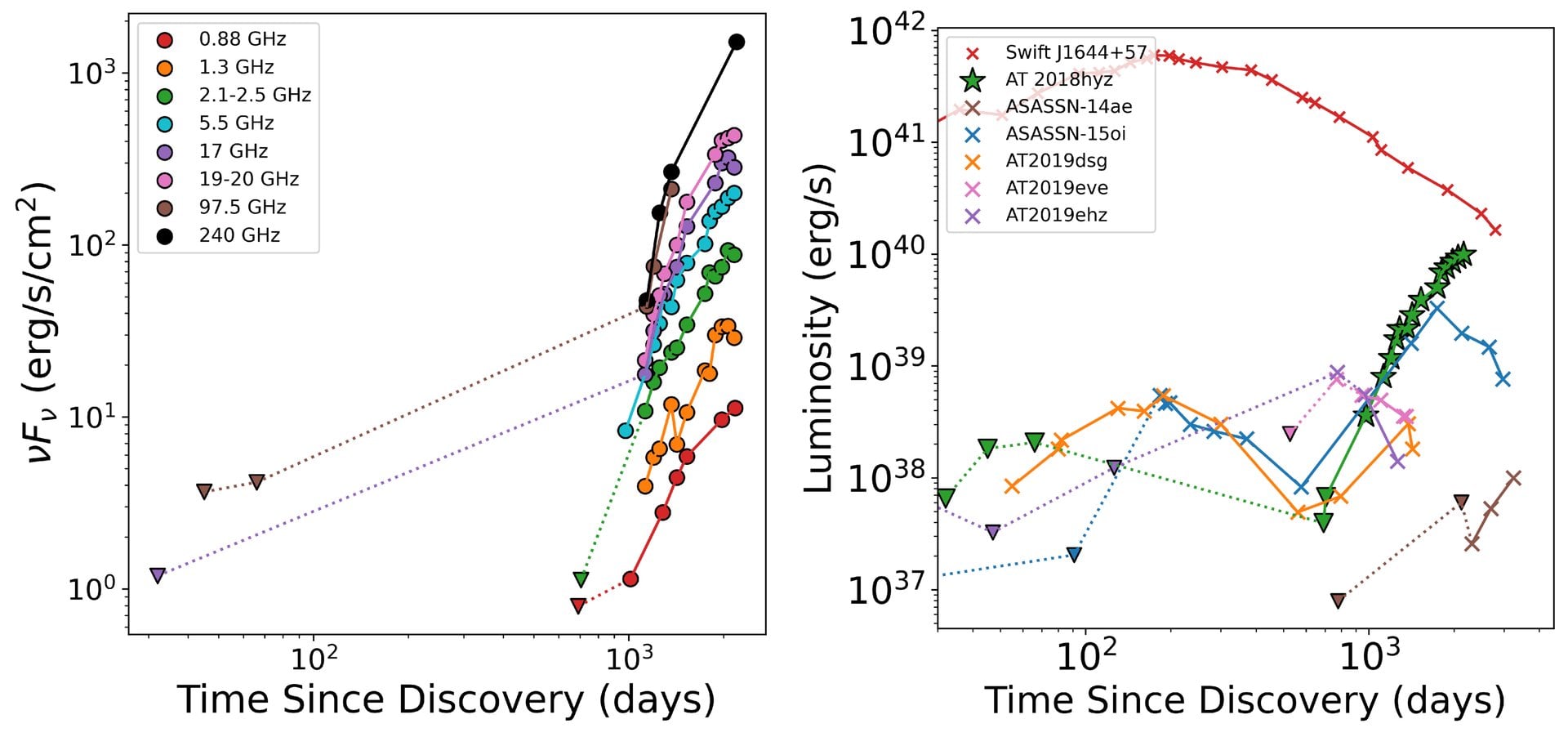

"We present ongoing radio observations of the tidal disruption event (TDE) AT2018hyz, which was first detected in the radio at 972 days after disruption, following multiple nondetections from earlier searches," the authors write. The researchers' new observations span from about 1370–2160 days after disruption. "We find that the light curves continue to rise at all frequencies during this time period..." they write.

*These panels illustrate the light curve coming from AT2018hyz. The left panel shows its radio emissions (y-axis) over time (x-axis) across multiple radio frequencies. The right panel compares AT2018hyz's emissions to other TDEs. Image Credit: Cendes et al. 2026. ApJ*

*These panels illustrate the light curve coming from AT2018hyz. The left panel shows its radio emissions (y-axis) over time (x-axis) across multiple radio frequencies. The right panel compares AT2018hyz's emissions to other TDEs. Image Credit: Cendes et al. 2026. ApJ*

The event was first observed in optical light in 2018, but at that time it was just another TDE. A few years after that, Cendes observed AT2018hyz again and discovered that it was emitting lots of energy in radio waves. They published a paper on the curious TDE in 2022. That paper pointed out the rising emissions, saying that "Such a steep rise cannot be explained in any reasonable scenario of an outflow launched at the time of disruption, and instead points to a delayed launch."

In the new paper, Cendes and her colleagues report that energy emitted by the SMBH has risen sharply in the intervening years. In fact, it's 50 times brighter now than it was when it was first first detected.

There are two potential scenarios to explain this rising radio luminosity. One is a "delayed spherical outflow." In this scenario, the outflow was launched about 620 days after the disruption. "The physical evolution of the radius for a spherical outflow supports an outflow that was launched with a substantial delay of about 1.7 yr relative to the discovery of optical emission," the researchers write.

The second scenario is an astrophysical jet. It would be highly off-axis and travelling at relativistic speeds. "The radio emission from an off-axis jet will be suppressed at early times by relativistic beaming but will eventually rise rapidly when the jet decelerates and spreads," the authors explain.

The research shows that the stream of radio waves coming from the SMBH will continue to rise until peaking in 2027.

“This is really unusual,” said lead author Cendes in a press release. “I'd be hard-pressed to think of anything rising like this over such a long period of time.”

When the researchers calculated the black hole's energy output, they were met with an additional surprise. It's about equal to the energy released by a gamma-ray burst (GRB). Since GRB are the brightest and most energetic explosions in the Universe, that makes the SMBH one of the most energetic events ever witnessed.

For fun, the authors compared it to the Death Star in Star Wars. Fans of Star Wars have calculated the energy output of the Death Star, and working with those numbers, the authors' calculations show that the SMBH is emitting at least one trillion times more energy than a fully operational Death Star. And the actual number could be as high as 100 trillion times more than the fictional WMD.

But these calculations are made from a long way away. Only ongoing observations can judge their accuracy.

The discovery raises an important question: are other black holes and TDEs out there in the cosmos also exhibiting the same rising radiation? The answer is that we don't know because nobody's really looked.

“If you have an explosion, why would you expect there to be something years after the explosion happened when you didn't see something before?” Cendes said. She also notes that acquiring observation time on the world's most powerful telescopes is extremely competitive. Now that they've found one SMBH with unusual luminosity, their proposals to search for more will carry more scientific weight.

It's worth noting that this isn't the only TDE with delayed radio emissions. But it's luminosity is extreme compared to others.

"We find that AT2018hyz is a unique TDE even within the population of TDEs with delayed radio emission, and future observations should allow us to distinguish between these scenarios," the authors write.

Cendes and her co-researchers are planning to continue their observations of AT2018hyz across multiple frequencies. This will allow them to "monitor the ongoing evolution of the outflow and of the circumnuclear medium," the authors conclude.

Universe Today

Universe Today