How to see the best meteor shower of the year.

It’s one of the better annual meteor showers, and 2025 is shaping up to give sky watchers a chance to see it at its best. If skies are clear this weekend, be sure to be vigilant for the Geminid meteors.

Prospects for the 2025 Geminids couldn’t be much better. The shower peaks on the night of this Saturday/Sunday (December 13th/14th), centered on 3:00 Universal Time(UT)/10:00 PM Eastern Time (EST). This favors the North Atlantic and surrounding regions including Europe and North America. The expected Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR) is 150 meteors per hour. The Moon phase is favorable this year, at a 25% waning crescent, rising just before 3AM local near the shower’s peak.

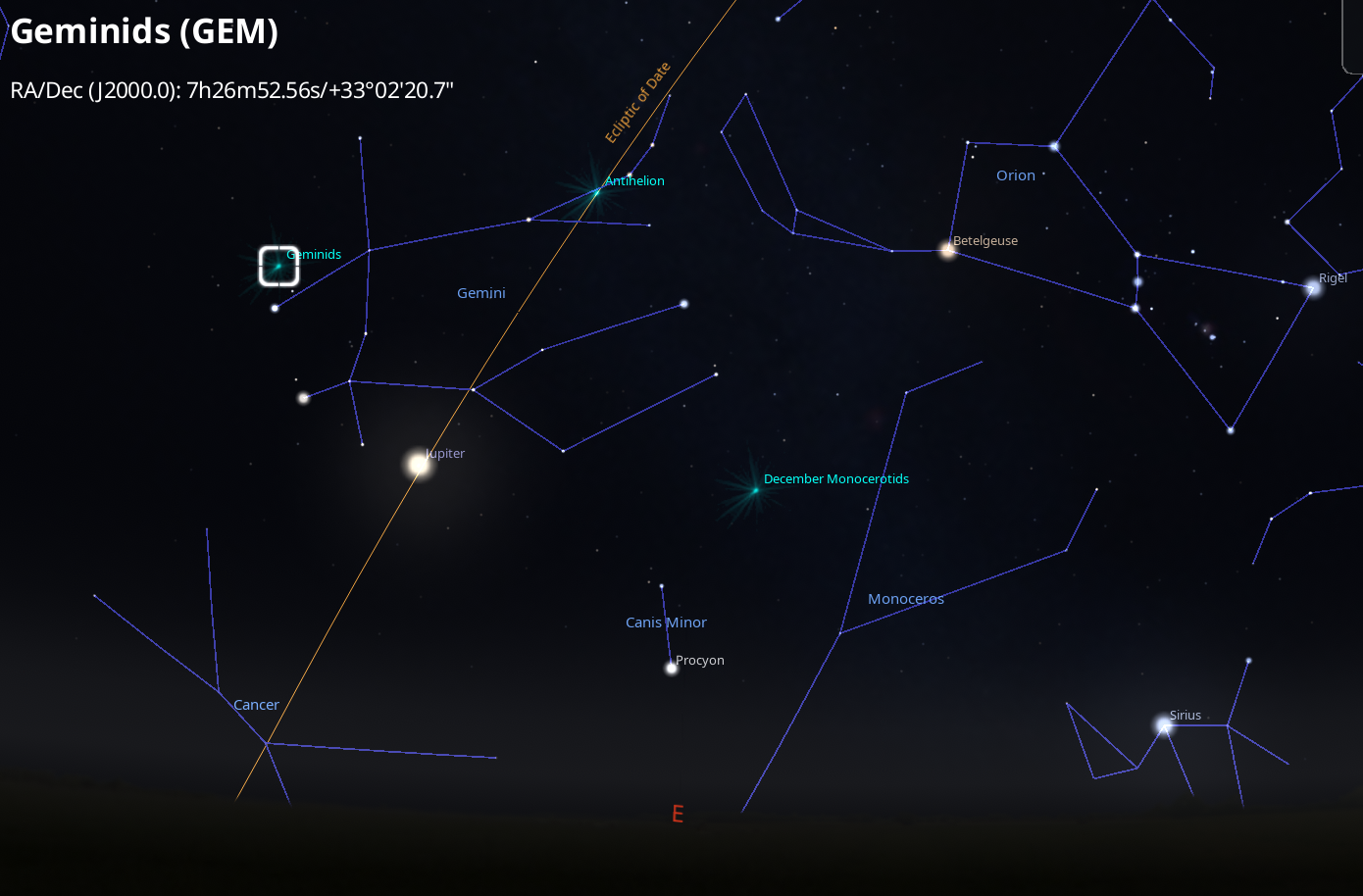

The Geminid radiant rising high to the east. Credit: Stellarium.

The Geminid radiant rising high to the east. Credit: Stellarium.

The ZHR is an ideal rate, an estimate of how many meteors you might see from a dark sky site if the meteor shower radiant is placed directly overhead.

Over the last few decades, the Geminids have put on a dependable annual show, rivaling only the Perseids in intensity. To be sure, the August Perseids have a better (and warmer) time of year going for them, but the Geminids tend to get underway before local midnight on chilly December evenings, which is a plus. This is because the Geminids are coming at us from a sideways path towards Earth. This also means they’re hitting our atmosphere at a medium-to-slow rate of 35 kilometers per second, on the slow end when it comes to meteors.

A bright Geminid fireball lights up the skies over Tucson, Arizona in 2017. Credit: Eliot Herman.

A bright Geminid fireball lights up the skies over Tucson, Arizona in 2017. Credit: Eliot Herman.

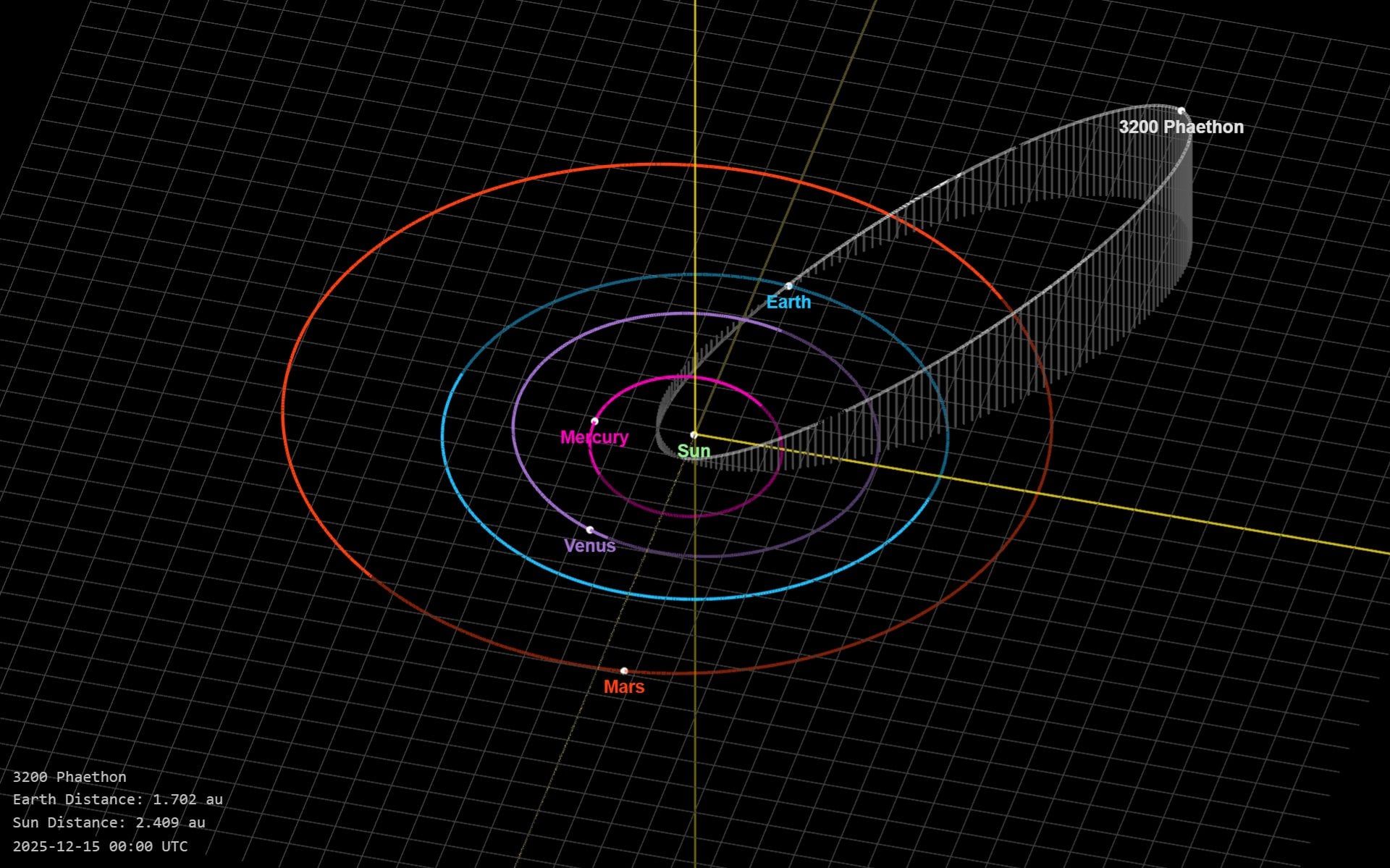

Though the shower was first identified as such back in 1862, the source of the Geminids was a mystery until 1983, when Fred Whipple pegged the shower’s stream as a good fit for the orbit of newly discovered short period asteroid 1983 TB, later named 3200 Phaethon. This object is in a tight 1.52 year orbit, and seems to be a dead comet nucleus getting alternatively frozen and baked as it loops around the Sun. We may finally get a look at rock-comet 3200 Phaethon up close in the coming years, when JAXA’s DESTINY+ mission launches in 2028 and heads to the enigmatic object. 3200 Phaethon made one of its closest passes near Earth for the 21st century on December 16th, 2017, at just over 10 million kilometers distant.

The orbit of rock-comet 3200 Phaethon. Credit: NASA/JPL.

The orbit of rock-comet 3200 Phaethon. Credit: NASA/JPL.

Most meteors are dust grains no bigger than pebble-sized. These burn up in the upper atmosphere as they run headlong into our planet. This is why rates tend to pick up after local midnight. This is when your observing site rotates forward into where the Earth is moving toward in its path around the Sun, versus looking back at where we’ve been in space. A good winter analogy can be seen looking forward into your headlights driving into a snow storm at night, with the oncoming ‘flakes’ seeming to come from a point straight ahead as a stand in for meteors.

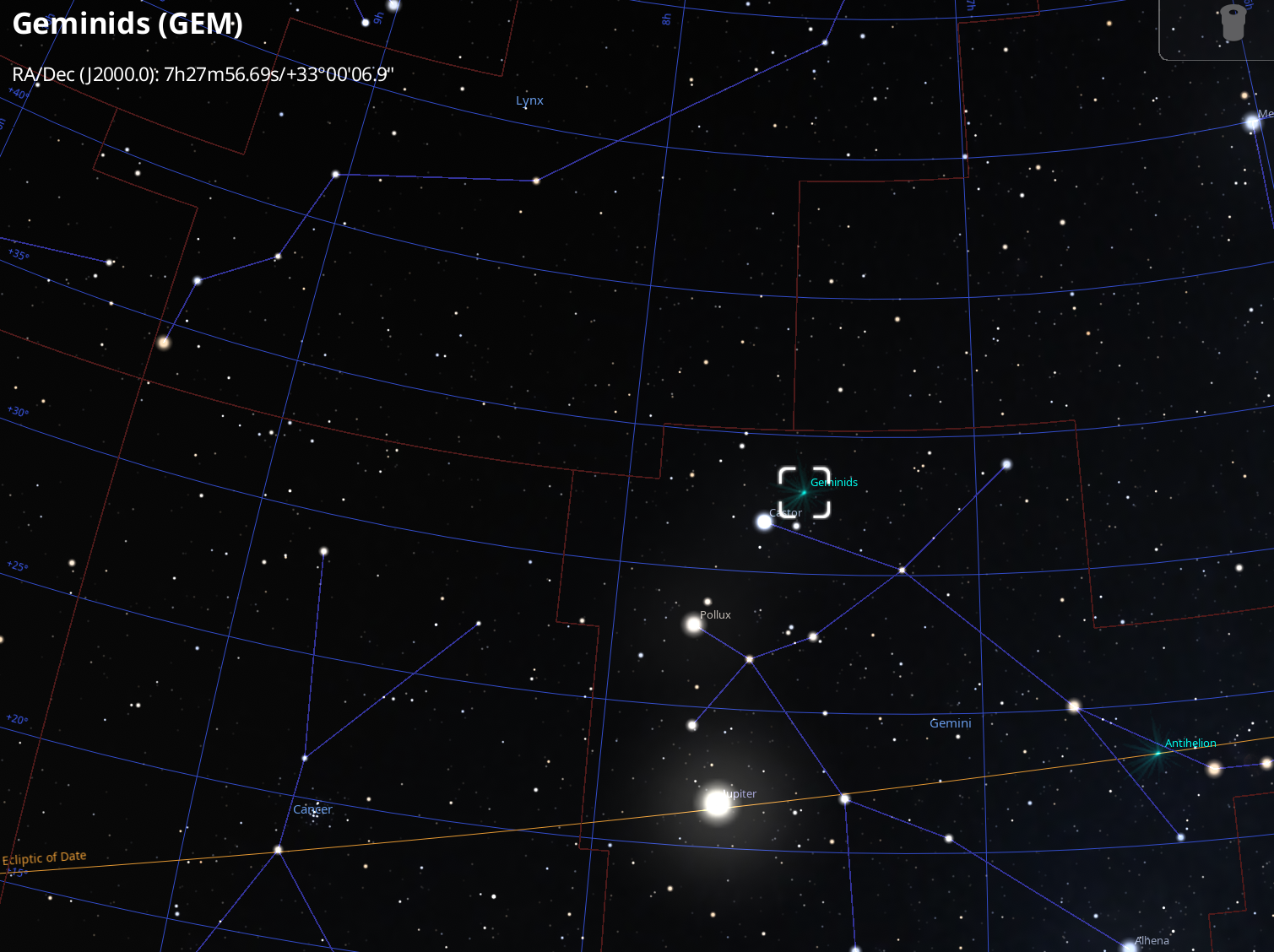

The Geminids hail from a point (the shower’s radiant) near the bright star Castor, but can appear anywhere in the sky. If you see a meteor defying this trend, it’s a sporadic or a member of a lesser known stream.

The Geminid meteor shower radiant in the constellation Gemini. Credit: Stellarium.

The Geminid meteor shower radiant in the constellation Gemini. Credit: Stellarium.

The Ursid meteors are also active in late December, with an expected ZHR around 10 on December 22nd at 10:00 UT. This shower peaks just a day after the southward solstice. The prospects for the Ursids are also favorable in 2025, as the Moon is still just a 5% illuminated, waxing crescent. Though the Ursids have a weak peak on most years barely above the sporadic background rate, they have produced occasional outbursts. This most notably occurred on 1945 and 1986, when the ZHR for the shower topped 100. The source of the Ursids is periodic comet 8P/Tuttle.

Observing the Geminids is as simple as watching at waiting. It’s worth keeping an eye on the sky a night or two before and after the expected peak, as activity can pick up prior to predictions, and still persist after. The Geminids have a broad, 22 hour peak. Dress warm, and bring a mug of your favorite hot beverage of choice. Getting away from bright lights will optimize how many meteors you’ll see.

Imaging meteors is as simple as setting a DSLR camera with a wide field of view on a tripod, and shooting a series of images and seeing what turns up. I like to take a quick series of test shots to get the ISO/f-stop and time exposures (usually 10 seconds to a minute) correct. Be sure to have a set of extra batteries ready in a warm pocket as well, as cold temperatures tend to kill batteries in a hurry. An intervalometer can automate the shooting process.

A montage of Geminid meteors from 2014. Credit: Mary McIntyre.

A montage of Geminid meteors from 2014. Credit: Mary McIntyre.

If you’re counting meteors, don’t forget to report what you see to the International Meteor Organization (IMO). It’s a good way to contribute to the science of meteoritics.

This weekend’s waning crescent Moon also offers a fine chance to watch for Geminids hitting the nighttime side of the Moon. Be sure to report what you see to the Lunar Impact Flash (LIF) project's Geminid Campaign. The European Space Agency also has plans to launch a smallsat mission named the LUnar Meteoroid Impacts Observer (LUMIO) in 2027 to watch for Geminid impacts on the lunar farside.

Clouded out? Watch the 2025 Geminids live on December 13th starting at 21:00 UT, courtesy of astronomer Gianluca Masi and the Virtual Telescope Project.

Don’t miss the December Geminids, as a great way to round out the skywatching year.

Universe Today

Universe Today