Jupiter is the largest planet in the solar system. It's also one of the largest planets in the Universe. There are planets out there with much more mass, but thanks to gravity, they are generally more dense, not "bigger." This raises an interesting question about massive exoplanets. Do they look similar to Jupiter? A new study finds they probably don't.

Before getting into the details, let's talk about the difference between a planet, a brown dwarf, and a star. Very broadly, a planet is massive enough to compress into a sphere under hydrostatic equilibrium but not massive enough to trigger any kind of nuclear fusion in its core. Stars are massive enough to trigger the fusion of hydrogen. Brown dwarfs lie in the middle ground. They are too small to trigger hydrogen fusion like a true star but large enough to have a bit of deuterium fusion. In terms of mass, anything up to about 10 Jupiters is a planet, anything over 90 Jupiters is a star, and brown dwarfs are the middle child.

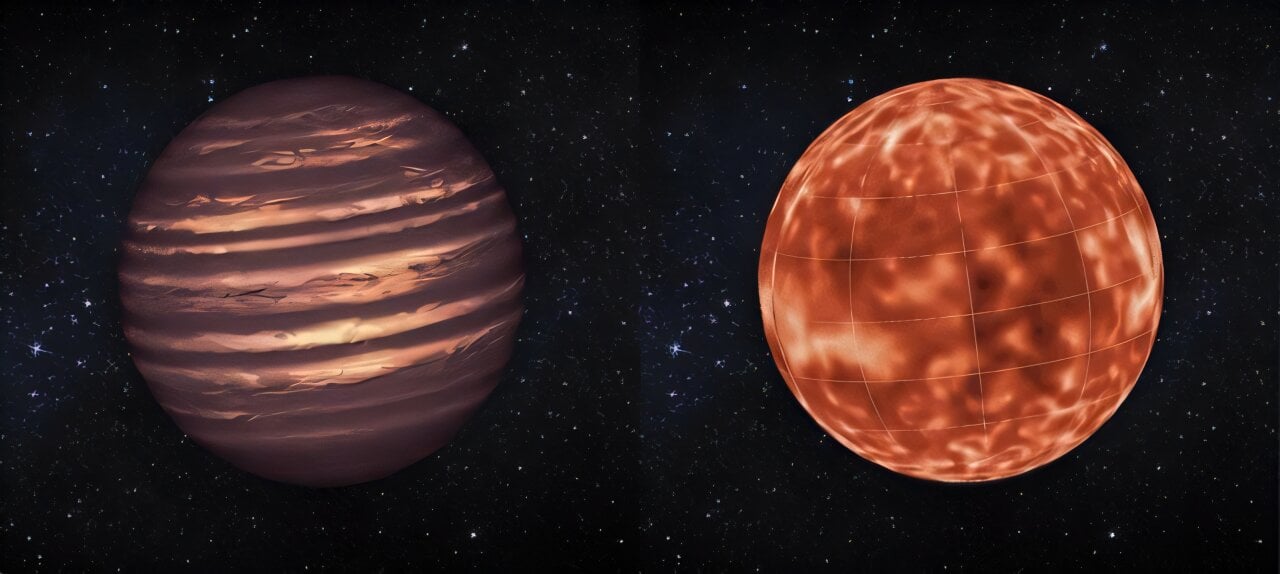

We've long known that the most massive brown dwarfs look very star-like. They can have surface temperatures of nearly 3000 K. If we were to see one up close, it would look like a deep red dwarf star. But what about the smallest brown dwarfs? With a mass of around 10 Jupiters, it would have a diameter slightly smaller than our largest planetary sibling and a surface temperature of a few hundred Kelvin. That's a bit warmer than Jupiter's 170 K, but not warm enough to glow. So generally we've imagined these "Super-Jupiters" to look very Jupiter-like. Most of the artistic representations show them as a gas planet with banded clouds similar to Jupiter or Saturn.

*A direct image of the exoplanet VHS 1256b and its star. Credit: ESO VHS*

*A direct image of the exoplanet VHS 1256b and its star. Credit: ESO VHS*

To test this idea, the new study looks at an exoplanet known as VHS 1256b. It has a mass of around 20 Jupiters and is one of the few exoplanets we can directly image. Images of the world from JWST show it is a reddish planet with a surface temperature of around 1300 K. It glows faintly in the deep red, so even with banded clouds, it would look like an alien world. But thanks to observations of its spectra, the team found evidence of large and dusty storms in its atmosphere. This causes the exoplanet to vary in brightness, similar to the fluctuations we see in tiny stars.

Based on this data, the team modeled the atmosphere of VHS 1256b and planets more similar to Jupiter. The banded cloud pattern we observe on Jupiter is caused by large winds moving parallel to its equator. Some winds stream eastward while others stream westward, creating the different cloud regions. This structure is reinforced by heat exchange between layers. But super-Jupiters are warmer, driving more energy into their atmospheres. The team found that the atmospheres of super-Jupiters react to the heat more strongly, creating turbulent regions that would break apart banded structures. In other words, many super-Jupiters wouldn't look like their smaller cousin but would have a more chaotic surface.

Super-Jupiters have a look all their own.

Reference: Tan, Xianyu, et al. "Large-amplitude variability driven by giant dust storms on a planetary-mass companion." *Science Advances* 11.48 (2025): eadv3324.

Universe Today

Universe Today