Gamma-ray bursts (GRB) are some of the most perplexing phenomena in Nature. Even though astronomers have detected about 15,000 of them, with a new one each day, they're still mysterious. They're the most luminous, energetic explosions in the Universe, and typically last only a few milliseconds, or a few minutes, with a handful of them lasting for a few hours.

GRBs that last longer than about two seconds typically come from supernova explosions where a high-mass star reaches the end of its life and collapses into a black hole. They produce focused, energetic jets that are ultrarelativistic. The tight focus of the jets means that most GRBs miss the Earth and are never detected, and all GRBs detected so far have been in distant galaxies.

When a GRB on July 2nd, 2025 lasted for seven hours, it highlighted how uncertain astronomers are about their causes.

The July 2nd GRB is named GRB 250702B and at seven hours long, it's the longest one ever detected. It lasted almost twice as long as the next longest-known GRB. In fact, it endured for so long that no single telescope could follow it.

Multiple papers have been published examining the GRB and discussing its implications. O'Connor et al. summed up the issue when they wrote that "GRB 250702B is a peculiar ultralong X-ray and gamma-ray transient that does not neatly fit into any class of known high-energy transients."

“The burst went on for so long that no high-energy monitor in space was equipped to fully observe it,” said Eric Burns, an astrophysicist at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge and a member of one of the research teams studying the burst’s gamma-ray glow. “Only through the combined power of instruments on multiple spacecraft could we understand this event.”

Astronomers used multiple telescopes to find the source. The Keck, Gemini, and VLT all suggested that it was coming from a distant galaxy. Astronomers used the Hubble to confirm that and to try to understand the source.

“It’s definitely a galaxy, proving it was a distant and powerful explosion, but it is a strange looking one,” said Andrew Levan, an astrophysics professor at Radboud University in the Netherlands who led the VLT and Hubble study. “The Hubble data could either show two galaxies merging, or one galaxy with a dark band of dust splitting the core into two pieces.”

Next it was the JWST's turn to observe GRB 250702B with its NIRCam instrument.

"The resolution of Webb is unbelievable. We can see so clearly that the burst shined through this dust lane spilling across the galaxy,” said Huei Sears, a postdoctoral researcher at Rutgers University in New Jersey who led the NIRcam observations. “It’s fantastic to see the GRB host in such detail.”

Later in the summer, another team of astronomers used the JWST's NIRSpec instrument and the Very Large Telescope to observe the location. That team was led by Benjamin Gompertz at the University of Birmingham in the U.K, and they began to realize just how distant and ancient this GRB was. “The burst was remarkably powerful, erupting with the equivalent energy emitted by a thousand Suns shining for 10 billion years,” Gompertz said. “Amazingly, the galaxy is so far away that light from this explosion began racing outward about 8 billion years ago, long before our Sun and solar system had even begun to form.”

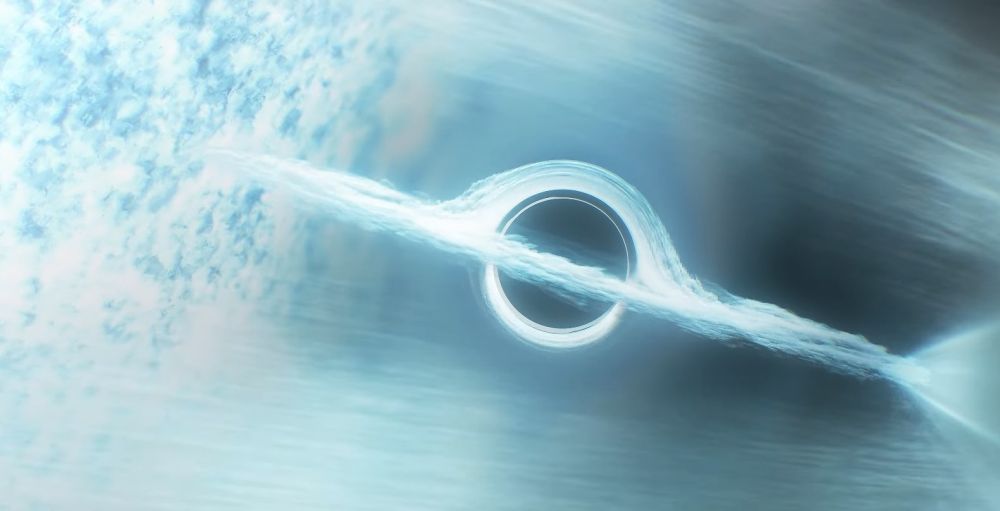

*An artist's illustration of GRB 250702B. It emitted powerful jets of gamma-rays that persisted for seven hours. The bursts came from a dusty galaxy about 8 billion light-years away. Image Credit: NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/M. Garlick*

*An artist's illustration of GRB 250702B. It emitted powerful jets of gamma-rays that persisted for seven hours. The bursts came from a dusty galaxy about 8 billion light-years away. Image Credit: NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/M. Garlick*

Astrophysicists think that most GRBs are caused by massive stars exploding as supernova. These events begin with a sharp emission of gamma-rays, followed by an afterglow of less energetic x-rays and other emissions that can last for days.

The Swift Observatory, Chandra Observatory, and NuSTAR observatories all watched the GRB and monitored its x-ray emissions after the main burst. They found rapid flares up to two days after the burst, much longer than expected.

“The continued accretion of matter by the black hole powered an outflow that produced these flares, but the process continued far longer than is possible in standard GRB models,” said Brendan O’Connor from Carnegie Mellon University, and lead author of one of the papers. “The late X-ray flares show us that the blast’s power source refused to shut off, which means the black hole kept feeding for at least a few days after the initial eruption.”

But GRB 250702B's x-ray emissions were different than other GRBs in another way, too. It showed signs of x-ray emissions that preceded the gamma-ray burst. Is this a clue to what caused this mysterious, long-lived GRB? Not only that, but most GRBs are in small galaxies, while this one is much more massive.

“This galaxy turns out to be surprisingly large, with more than twice the mass of our own galaxy,” said Jonathan Carney, a graduate student at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Carney is the lead author of a detailed study into the GRB.

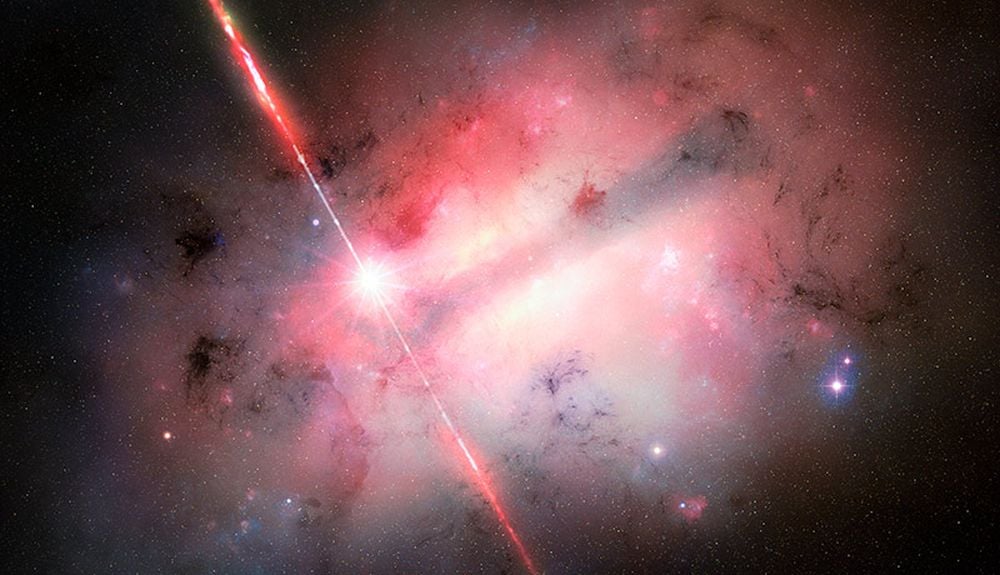

The JWST captured this image of the galaxy that hosts GRB 250702B. It eliminates the possiblity that the SMBH in the galaxy's center was responsible for the GRB. Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, H. Sears (Rutgers). Image processing: A. Pagan (STScI)

The JWST captured this image of the galaxy that hosts GRB 250702B. It eliminates the possiblity that the SMBH in the galaxy's center was responsible for the GRB. Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, H. Sears (Rutgers). Image processing: A. Pagan (STScI)

There are two likely explanations for this GRB, though neither are totally certain. Both involve a black hole eating its stellar companion.

The first one features an elusive intermediate-mass black hole (IMBH) with a few thousand solar masses, and a radius only a few times larger than Earth. Another star got too close to the IMBH, was stretched or "spaghettified", and then was quickly absorbed by the black hole. This is a typical TDE (Tidal Disruption Event) only the black hole is much more massive than a typical stellar-mass black hole.

The second scenario is also a TDE, but the black hole is a stellar-mass black hole with about three solar masses. But in this case, the BH is only about 18 km across, and the star is its binary companion. The companion star has a mass similar to the BH's, but is much smaller than the Sun. It's smaller because it's a helium star; its outer layer of hydrogen has been stripped away. In this scenario, the BH actually falls into the star, and once immersed, it rapidly consumes it from within, triggering the GRB.

In both cases, the BH begins by drawing matter from the star, forming a disk around the black hole where material eventually falls into the black hole, across the event horizon. The x-rays detected before the GRB come from the gas in the disk, which is heated as it accumulates in the disk. Later in the process, the BH rapidly devours the star which triggers the GRB.

But the second scenario would leave additional evidence. As the stellar-mass BH merged with the helium star, the energy it released would cause a supernova explosion. Supernovae explosions are hard to miss, but in this case, none was detected. That's probably because if it happened, it was hidden by thick dust. Even the powerful JWST can't see it through all that dust.

There are other possible scenarios. It's possible that a collapsar is responsible, or that a micro-TDE is behind it.

For now, the cause of the longest-ever GRB is unclear. It's multiwavelength nature and its long duration make it challenging to understand, and several possible scenarios could explain it.

"The multiwavelength signatures of the longest-duration GRB 250702B make it a unique puzzle that may originate from a novel progenitor," Carney and his co-authors write in their conclusion.

Universe Today

Universe Today