Apollo astronauts discovered an unexpected enemy on the Moon. Fine dust, kicked up by their movements and attracted by static electricity, coated everything. It found its way through seals, scratched visors, and clung to suits despite vigorous brushing. Eugene Cernan described it as one of the most aggravating aspects of lunar operations. More than five decades later, as humanity prepares to return to the Moon with increasingly sophisticated equipment, solving the lunar dust problem has become critical.

Researchers from the Beijing Institute of Technology, China Academy of Space Technology, and Chinese Academy of Sciences have now developed a detailed theoretical model that explains precisely how charged dust particles interact with spacecraft surfaces during low velocity collisions.

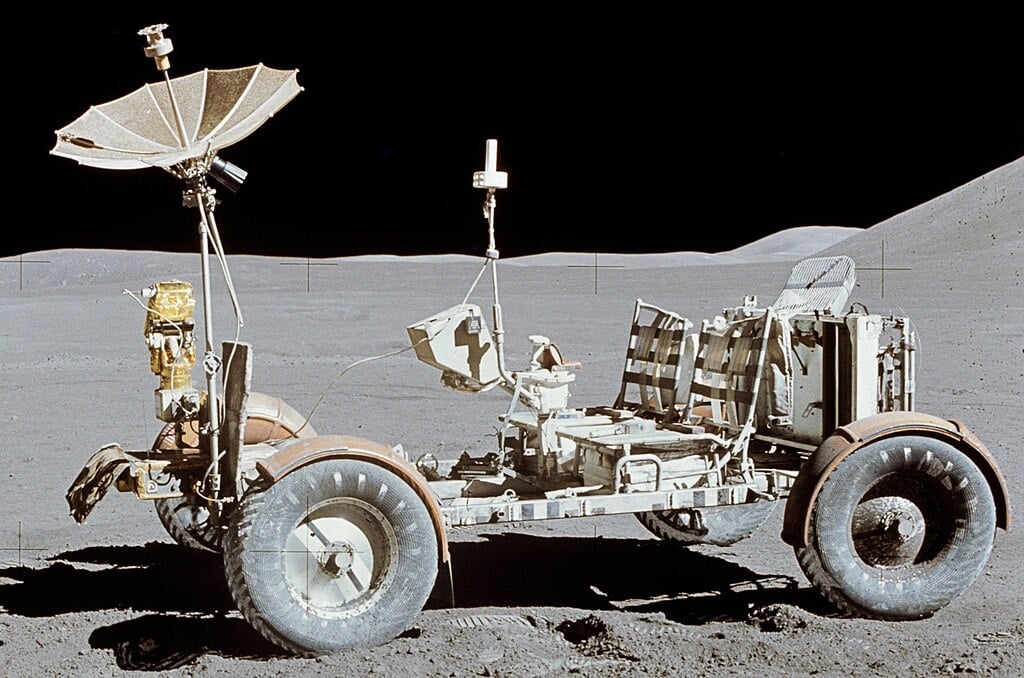

The lunar regolith has been the subject of a recent study into space exploration and the impact it causes (Credit : NASA)

The lunar regolith has been the subject of a recent study into space exploration and the impact it causes (Credit : NASA)

The challenge begins with the Moon’s harsh environment. On the dayside, intense solar ultraviolet and X-ray radiation strips electrons from both spacecraft and the lunar surface, leaving them positively charged. This creates a photoelectron sheath hovering above the ground. On the nightside, spacecraft and regolith instead collect electrons from the surrounding plasma, becoming negatively charged and forming what’s called a Debye sheath. The solar wind adds another layer of complexity, continuously bathing everything in charged particles.

Within this electrically active environment, dust particles themselves become charged and experience three distinct electrostatic forces as they approach a spacecraft. The electric field force acts on the particle’s surface charge, pulling it toward or pushing it away from the vehicle depending on whether their charges are opposite (attracting) or the same (repelling).

The dielectrophoretic force arises because the dust particle distorts the non-uniform electric field around it, creating an attraction toward regions of stronger field regardless of the particle’s charge. And the image force emerges when the approaching charged particle creates an opposite charge in the spacecraft’s conductive surface, similar to how a balloon sticks to a wall, creating an additional attractive pull.

The researchers’ model treats these electrostatic interactions in wonderful mathematical detail, but also recognises that other forces dominate once contact begins. When a dust grain actually strikes a spacecraft coating, adhesive van der Waals forces between molecules at the surface become dominant, particularly for the slow velocity impacts common during lunar operations.

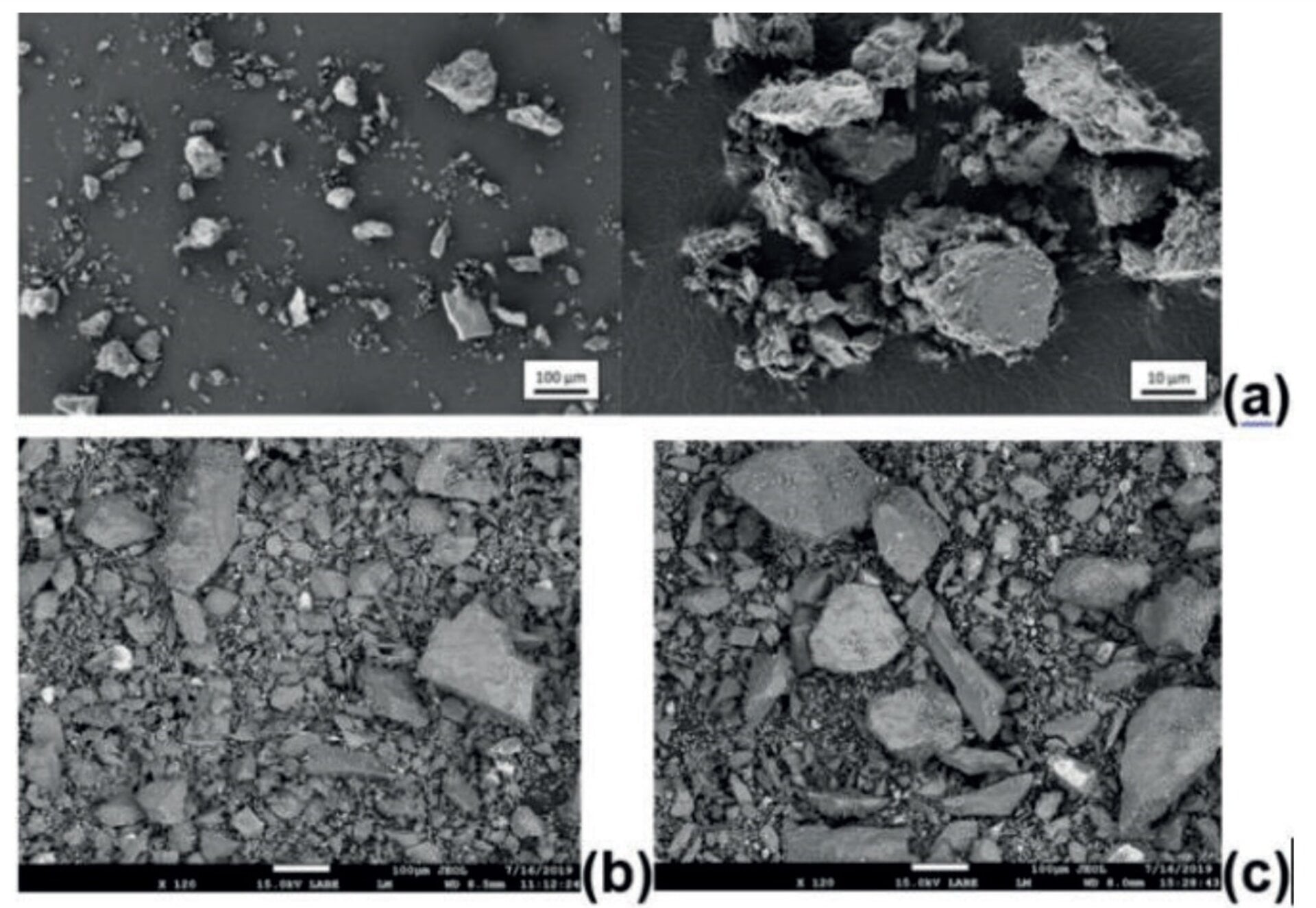

Close up of the lunar regolith (Credit : NASA)

Close up of the lunar regolith (Credit : NASA)

The collision itself unfolds in three stages. First comes adhesive elastic loading, where the particle compresses against the coating while attractive forces between the surfaces grow. If the impact is energetic enough, the coating begins to deform, dissipating energy as the material yields. Finally, during the unloading stage, the particle either bounces away or remains stuck, depending on whether the collision velocity falls within a critical range.

The model reveals several practical insights. A dielectric coating with high thickness and low permittivity (ability to store an electrical charge) can substantially reduce the electrostatic attraction between charged dust and spacecraft. The particle’s surface charge density matters more than the spacecraft’s electrical potential in determining the strength of electrostatic forces. And surprisingly, for particles carrying typical charge densities below 0.1 milliCoulombs per square meter, the adhesive van der Waals force overwhelms electrostatic effects during actual contact.

Perhaps most useful for mission planners, the research shows that coatings made from low surface energy materials with rough textures can significantly reduce dust adhesion. Larger particles tend to have higher coefficients of restitution, meaning they’re more likely to bounce away rather than stick. And there exists a critical velocity range for negatively charged particles where adhesion occurs, impacts slower or faster than this window allow particles to escape.

This new model can predict dust accumulation patterns, guide the selection of surface coatings, and help optimise dust removal systems. As missions to the Moon grow more ambitious and long duration, solving the sticky problem of lunar dust moves from an annoyance to an operational necessity.

Source : Modelling of electrostatic and contact interaction between low-velocity lunar dust and spacecraft

Universe Today

Universe Today